Tales of the Unexpected

We’ve just finished celebrating Family History Month, which offered us an opportunity to reflect on some of the unexpected connections to be found in Libraries Tasmania’s archival and heritage collections. In this post, we explore four ‘rare books’ that were not written here, not published here, not about Tasmania in any way, but which unfold extraordinary Tasmanian stories through the history of their ownership and use. From a 17th century Bible once held in royal hands, to a 19th century tanner’s technical manual, here are some tales of the unexpected uncovered in the State Library of Tasmania.

Tobias Rustat’s Bible

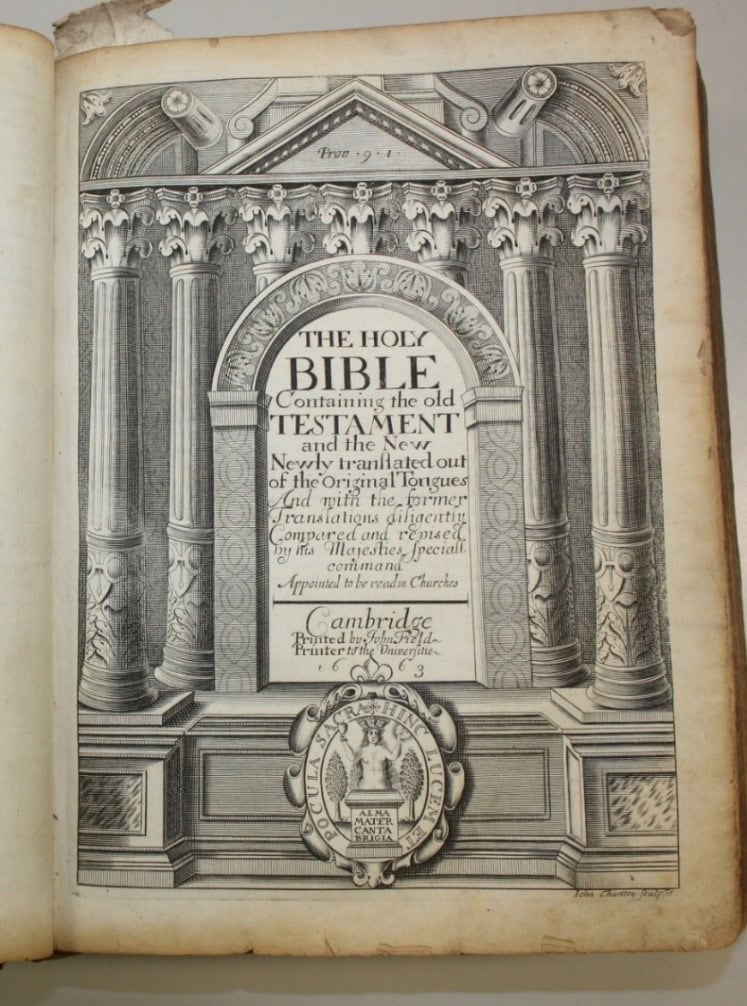

For an institution that has never deliberately sought to develop a ‘Rare Books’ collection, Libraries Tasmania has a surprising number of early printed books, including several Bibles. Some, like two early King James Bibles (a small octavo edition of 1615, and a folio edition of 1616), were used as ‘Family Bibles’, and contain handwritten lists of births and deaths. Other, still older volumes date from 1560 and 1593 and are in Greek and Latin. Their inscriptions and histories link to tales of the Reformation and Wars of Religion in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Other Bibles in the Crowther collection tell more recent stories – like missionary texts published in a range of Pacific languages (see our earlier blog on Te Bibilia Tapu Rau)

For an institution that has never deliberately sought to develop a ‘Rare Books’ collection, Libraries Tasmania has a surprising number of early printed books, including several Bibles. Some, like two early King James Bibles (a small octavo edition of 1615, and a folio edition of 1616), were used as ‘Family Bibles’, and contain handwritten lists of births and deaths. Other, still older volumes date from 1560 and 1593 and are in Greek and Latin. Their inscriptions and histories link to tales of the Reformation and Wars of Religion in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Other Bibles in the Crowther collection tell more recent stories – like missionary texts published in a range of Pacific languages (see our earlier blog on Te Bibilia Tapu Rau)

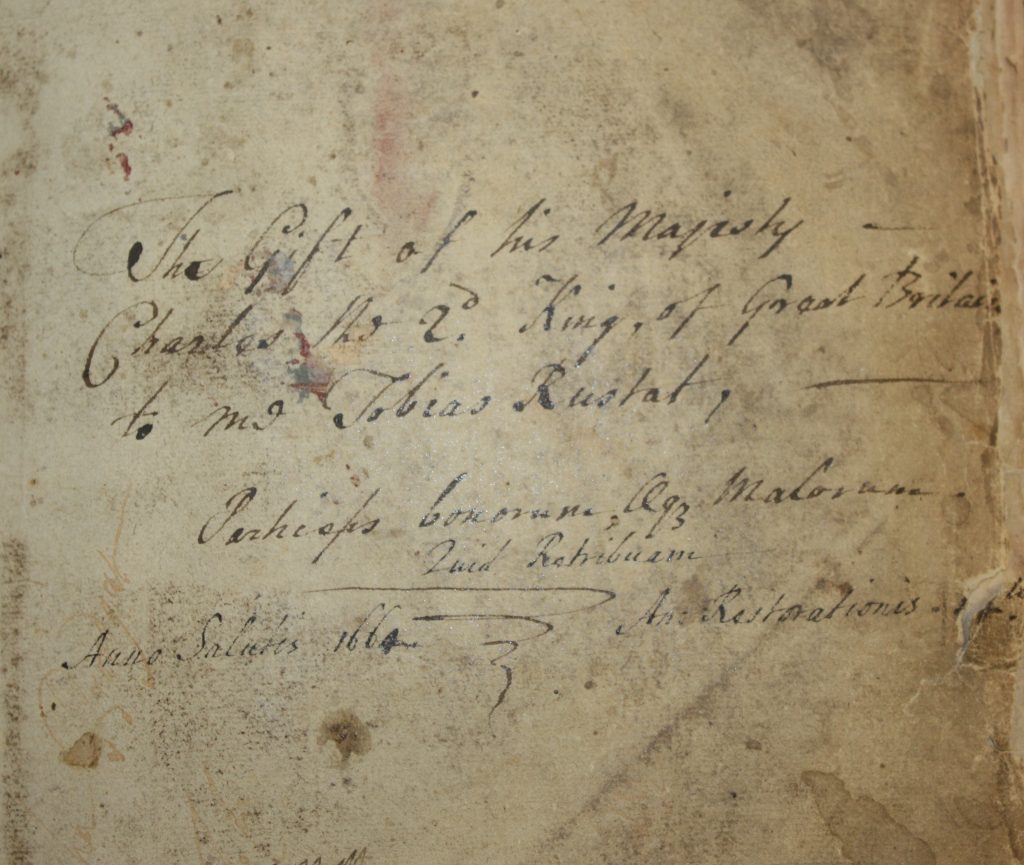

Rustat’s biography is fascinating: a clergyman’s son, he was apprenticed to a barber-surgeon in the 1620s before becoming a servant to England’s Ambassador to Venice. His loyalty to the Royalist cause during the years of the English Civil Wars and Oliver Cromwell’s Protectorate culminated in his appointment as Yeoman of the Robes to King Charles II, and an additional role at Hampton Court Palace under Charles II and his brother James II. Rustat’s career in the King’s service – ultimately responsible for managing the royal wardrobe, and the gardens at Hampton Court – made him a wealthy man, who gave away £11,000, equivalent to around $2.5 million today. These included substantial endowments to the library of Cambridge University.

Among the books that stayed in the family was the Bible that is now in the collection of Libraries Tasmania. The Bible, inscribed by Charles II to Rustat in 1664 – ‘anno restorationis quarto’, year four of Restoration – passed to his nephew, also named Tobias, and from him to his descendants the Parsons family.

Charles Octavius Parsons (1799-1863) emigrated to Van Diemen’s Land in 1823, and was appointed commissariat storekeeper at Macquarie Harbour. After disputes with Captain James Butler and Major Thomas Lord, he returned to England in 1829. He came back to Van Diemen’s Land in 1831, married Maria Jennings (1802?-1881), a cousin of the powerful Gellibrand family, and – after unsuccessfully seeking reinstatement in the public service – became a pastoralist. The Rustat Bible was gifted to the Allport Library and Museum of Fine Arts by Charles Octavius Parsons’s descendent, Charles Parsons (1934-2018).

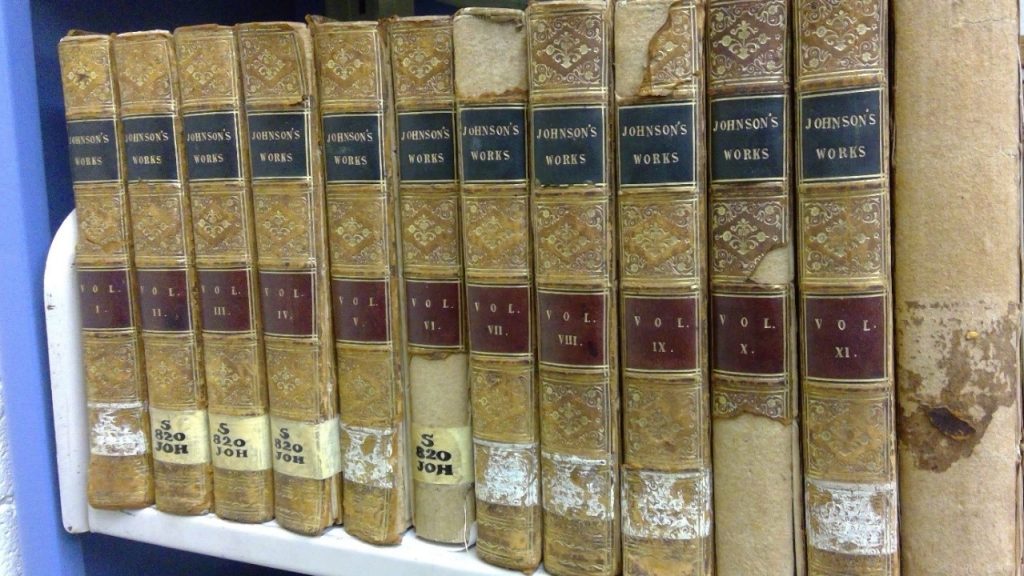

Matthew Arnold’s History Prize

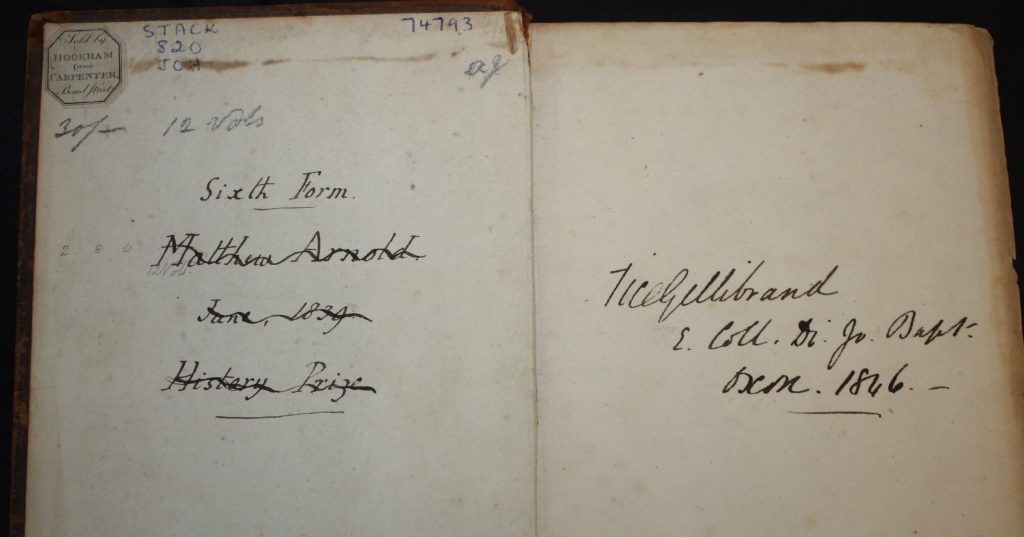

Squirrelled away in one of the more obscure corners of the State Library building in central Hobart is a loved-to-death 12-volume set of the works of Dr Samuel Johnson (1709-1784), described in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography as ‘arguably the most distinguished man of letters in English history’.

There is no evidence as to its original owner, but in 1839 it was given as a school history prize to then 17-year-old Matthew Arnold – son of the famous educator Dr Thomas Arnold. It seems that he then gave it to a friend of his – Joseph Tice Gellibrand, Jr, a fellow-student at Oxford, who ended up travelling to Tasmania in 1851 – at the same time as Matthew Arnold’s brother Thomas. The story of the two families and one set of books is a tangled web of globe-trotting coincidence, with ties to some of the great scientific and literary minds of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

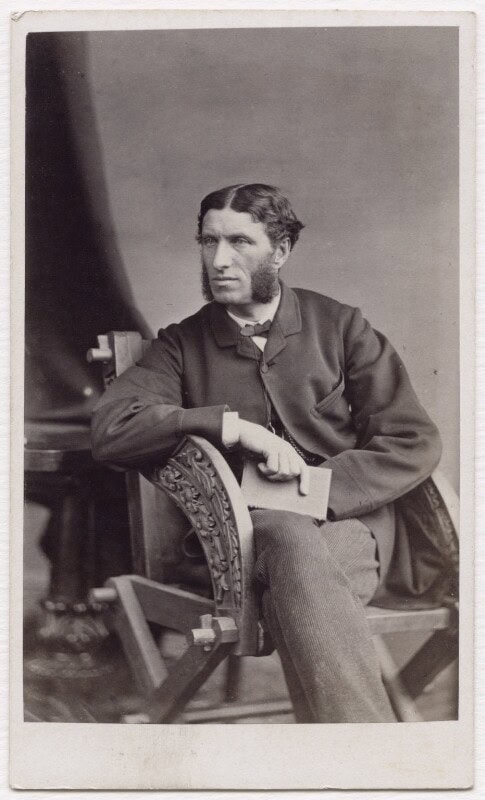

Matthew Arnold (1822-1888) was an influential English poet, critic and school inspector. His father was the teacher and historian Thomas Arnold (1795-1842), who was Headmaster at Rugby School from 1828 to 1841, and Regius Professor of Modern History at the University of Oxford from 1841 until his death in 1842. His time at Rugby is described in Thomas Hughes novel, Tom Brown’s Schooldays (1857), a book that influenced British education systems well into the 20th century – and created the archetypal school bully, Harry Flashman, whose adult escapades were chronicled by 20th century novelist George MacDonald Fraser. Rugby was a model for Hobart’s Hutchins School, established in 1846, and the Tasmanian Archives holds the Hutchins Admission Registers from 1846-1892 (NS36).

As for Matthew – he won a scholarship to Balliol College, Oxford in 1841, and was elected a Fellow of Oriel College in 1847. During this time he gave his school-prize set of Samuel Johnson to a fellow student, Joseph Tice Gellibrand, Jr. We don’t know why. His later writings make it clear that he admired Johnson’s work. Most people treasured school prize books, and handed them down through the generations until they literally fell apart. But Matthew Arnold won numerous academic prizes, and perhaps it was simply that he had acquired a better edition of Johnson and wanted to make space on his shelves. His 1878 book The Six Chief Lives from Johnson’s ‘Lives of the Poets’ is based on the 1781 edition, ‘the first to have a complete and correct text’ (preface, p. xv). Whatever Matthew’s reasons for parting with his history prize, the story of these books and the two families doesn’t end there, but it goes on to join up with the life of Matthew’s brother, Thomas Arnold at the other end of the world.

Tom Arnold (1823-1900), like his father and his other brothers, was also a writer and an educational administrator – but in Tasmania and New Zealand as well as in the UK and Ireland. Tom graduated from University College, Oxford with a First Class degree in 1845, but, disillusioned with English society, he emigrated to New Zealand in 1848 where he established a school. In 1850, he moved to Hobart, where he met and married Julia Sorell (1826-1888), who is the subject of a brand-new biography by Mary Hoban, An Unconventional Wife: The Life of Julia Sorell Arnold. And it was here that he would have run into his brother’s university friend (and probably his, too), the Rev. Joseph Tice Gellibrand, Jr.

Gellibrand was born in Tasmania, but left not long after his father (Joseph Tice Gellibrand Snr) disappeared in 1837 exploring Port Phillip. The younger Gellibrand returned to England, studied at Oxford, was ordained as a minister in the Church of England, married Hannah Evans and returned to Tasmania in 1851, where he ended up at All Saints in South Hobart. It was here that he most likely joined up again with the Arnolds – at least for a little while, before scandal rocked the Arnold family.

Not long after his marriage to Julia Sorell, Tom Arnold converted to Roman Catholicism, a move that infuriated his wife and obliged him to resign from the Tasmanian public service. They returned to England in 1857, and Tom took an academic position at the Catholic University in Dublin – where one of his last students was the novelist James Joyce (1882-1941). Meanwhile, the Gellibrands travelled around the world, between Tasmania, New Zealand and Britain several times

The Arnold family’s connections stretched into many corners of nineteenth and twentieth century science and literature. The Arnolds’ children included Mary (1851-1920) who, under her married name Mrs Humphry Ward, became a bestselling novelist. Another daughter, Julia, married Leonard Huxley (1860-1933), son of the eminent scientist Thomas Henry Huxley (1825-1895) – one of Charles Darwin’s closest collaborators and a key supporter of the theory of evolution by natural selection. The Huxleys’ children included the novelist Aldous Huxley (1894-1963), and biologist Julian Huxley (1887-1975).

But the books – the set of Johnson’s works given to one brother as a prize, given to a friend for reasons unknown, and which then travelled to the other end of the world – stayed behind in Tasmania, where they were eventually donated to the State Library, as an enduring record of globetrotting friendships.

In notes written shortly before his death, Tice listed the ‘men and women whose lives and characters have influenced me most during my career’. Besides his wife and several Biblical figures, the list ranged from Giuseppe Garibaldi to Florence Nightingale, and Sir John Franklin. It also included ‘Dr Arnold of Rugby’, and Samuel Johnson.

Mrs Fletcher’s Music Albums

Librarians don’t usually buy books because they are damaged. If a book is rare enough, we may buy it despite its condition, but for the damage to be the main reason for acquisition is rare indeed.

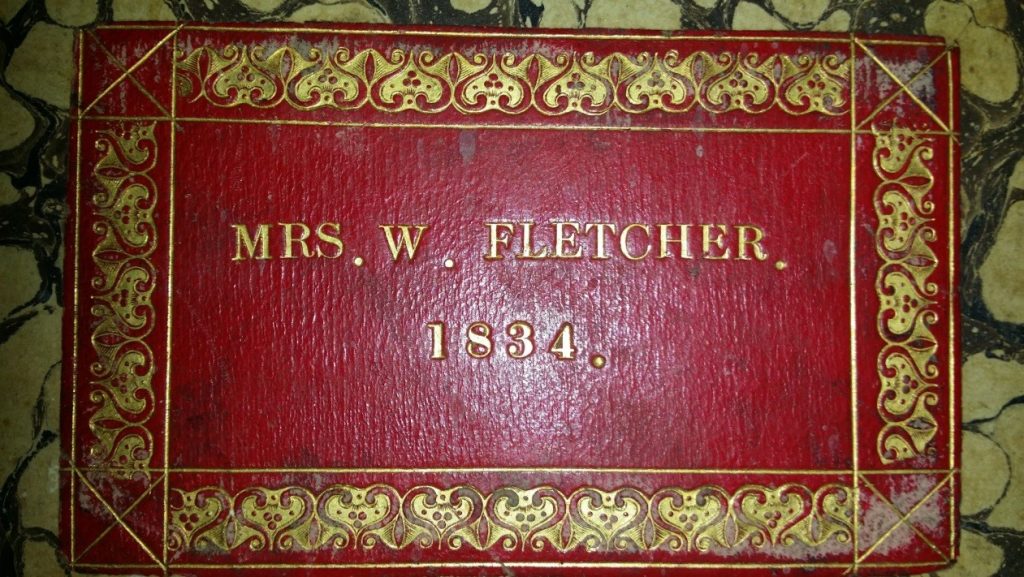

In 2014 a Melbourne bookseller contacted the Allport Library, offering three volumes of early nineteenth century music. The music was mostly printed in London or Dublin, well outside Allport’s collecting scope. The binding was very finely crafted, and each volume had an elegant label on its front cover, ‘Mrs W Fletcher 1834’.

But, frankly, ‘Mrs W Fletcher’ could have been anybody. Obviously wealthy, and interested in music, but without anything more concrete to connect her to Tasmania the library had no reason to be interested.

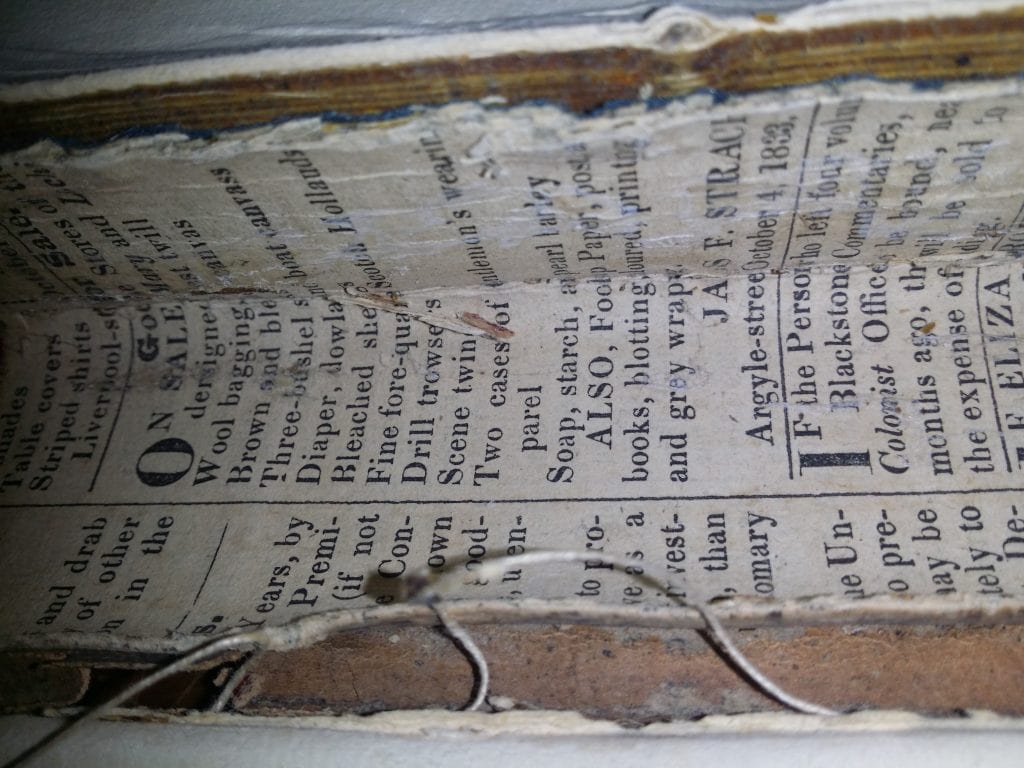

This is where the damage came in. The binding of the first volume was broken, exposing some of the lining – fragments of an old newspaper, the Colonial Times (Hobart) from October 1833.

‘Mrs W Fletcher’ was the wife of William Fletcher (1796-1872), the Deputy Commissary General. As a clerk in the Commissariat Department, William had been assigned to the Duke of Wellington’s army in Spain and Portugal during the Peninsular War from 1812-1814. He was posted to the West Indies in 1816, and to Van Diemen’s Land in 1824, where he and his family became central figures in Tasmanian society.

In 1826 William Fletcher married Hannah (ca.1804-1879), daughter of the then Acting Attorney-General Joseph Hone. Hannah’s uncle (her father’s brother) was the writer and bookseller William Hone (1780-1842), regarded as a ‘father of the modern media’ for his crusading journalism and his successful legal challenges to official censorship. William and Hannah Fletcher’s daughter Hannah Mary Ann (1827-1878) married Hobart businessman and amateur artist William Knight (1809-1877) in 1846. Several of Knight’s paintings and drawings are in the collections of the Allport Library and Museum of Fine Arts.

In short, Mrs Fletcher’s music albums offer evidence of the cultural life of a family at the centre of Hobart’s cultural and political life in the 1830s. Without the damage to the spine of the books, no one would have made the connection.

But who was the bookbinder? Early colonial bindings are mostly plain and simple, utilitarian, often crude. These volumes are the work of an accomplished craftsman with access to the finest materials. They pre-date the arrival of the best-known colonial Hobart bookbinder, George Rolwegan (1812-1866), by almost a decade.

Mrs Fletcher’s albums were almost certainly bound by George Henry Peck (ca.1810-1863). He arrived in Hobart in June 1833, quickly acquired a reputation as a violin virtuoso, and by early 1834 was advertising as a ‘carver, gilder, ornamental designer and binder’. He also offered music lessons, and was involved in a wide variety of musical and theatrical productions, including at John Pascoe Fawkner’s Cornwall Hotel Assembly Room. We cannot prove, but it seems reasonable to assume, that he performed some of the music he bound for the Fletchers.

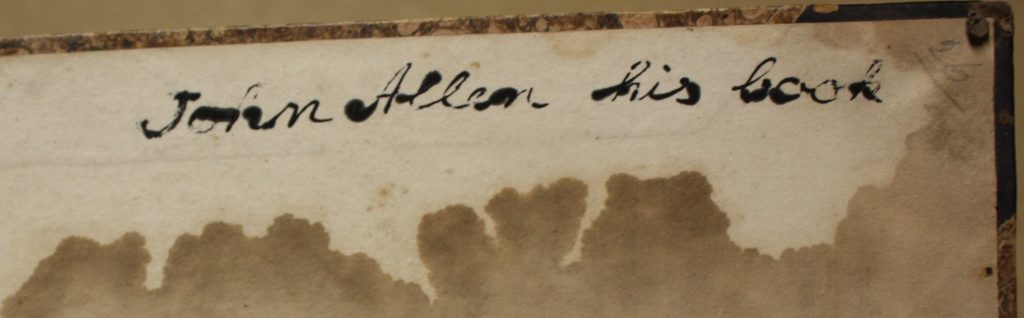

John Allen and The Art of Dy[e]ing

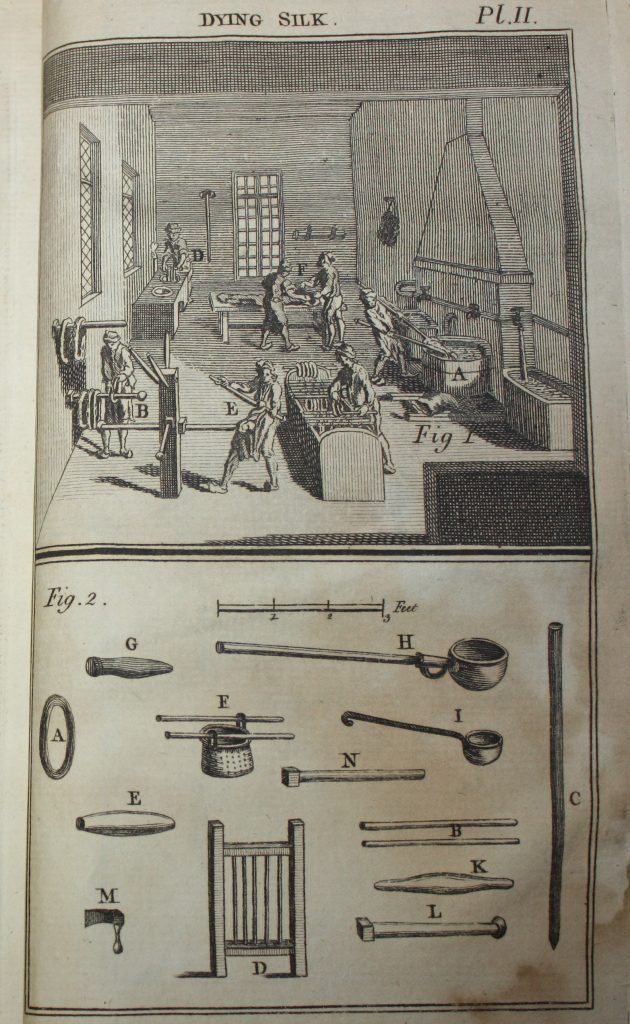

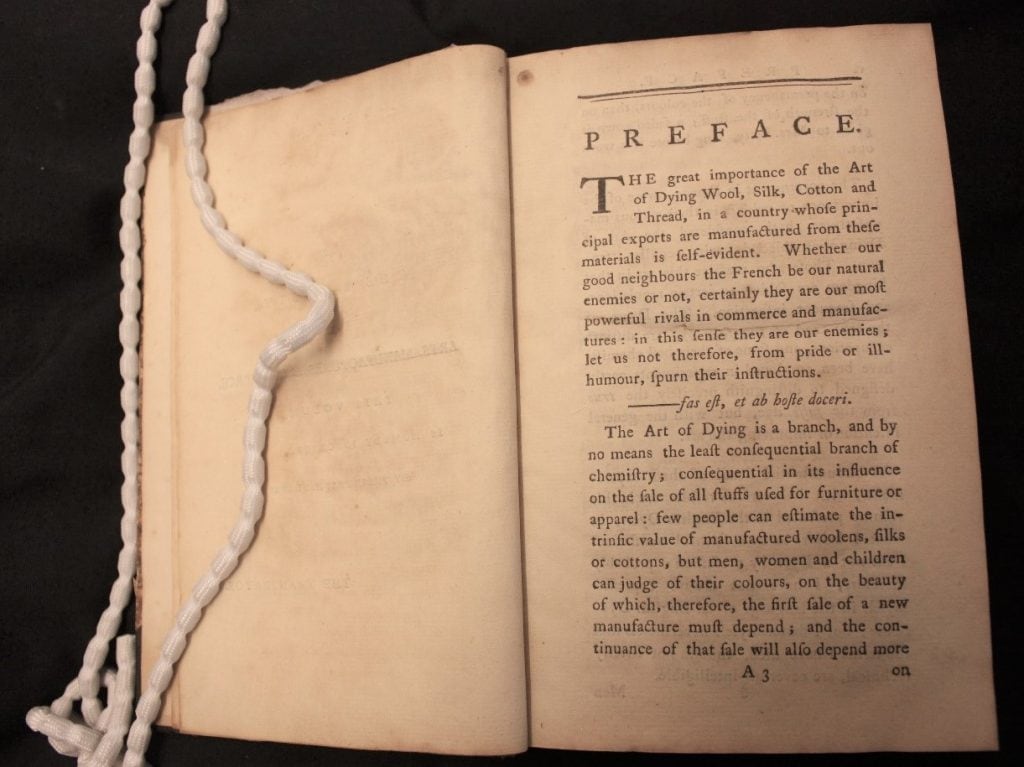

A working copy of technical manual, belonging to an identifiable 19th-century Tasmanian tradesman, is a rare treasure. By definition, such books are everyday tools and seldom outlive their working lives in useable condition.

John Allen’s copy of The Art of Dying (1789) is one such survivor. Although stained, and clearly heavily used, it remains in fine, robust condition.

The Art of Dying was an essential book for anyone working in the clothing and textile industries in the 18th and 19th centuries. It was the first systematic technical treatise on dyeing wool. First published in Paris in 1750 as L’art de la teinture des laines et étoffes de laine au grand et au petit teint, it became a standard text for the industry. English translations were published in Dublin (1767), Paris (1785) and London (1789).

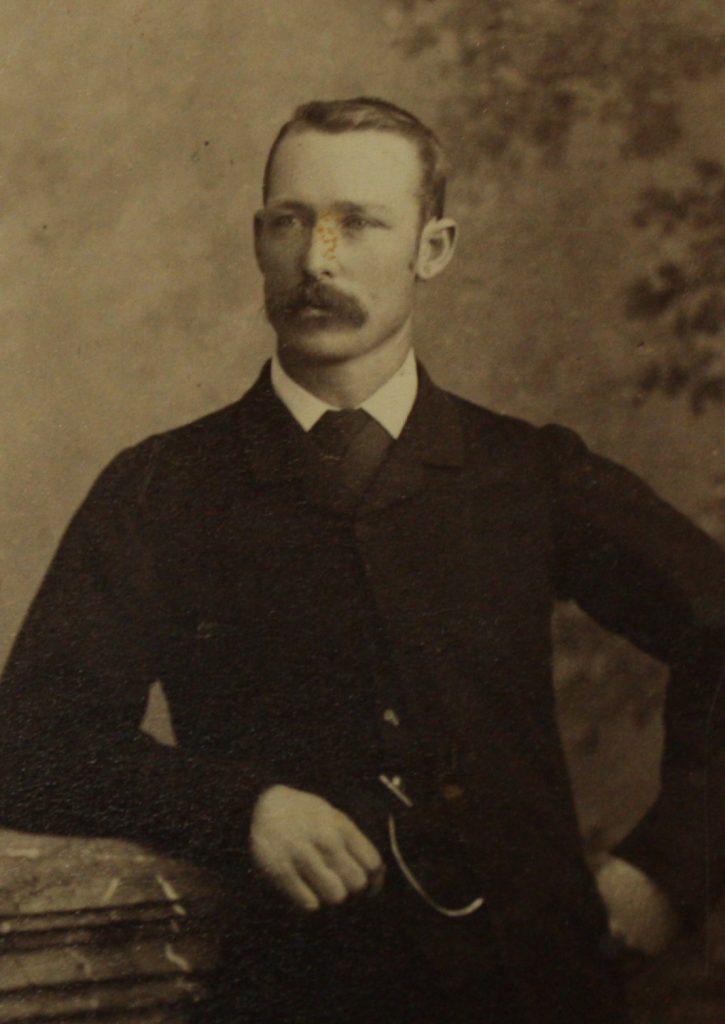

John Allen (1857-1917) worked for Samuel Burrows, Risdon Road, New Town, and later dressed and dyed leather, sheepskins, possum skins and the like at his property 200 Risdon Road – using the book that was by then 100 years old.

He married Effie Belinda Lewis in 1892. They had eight children. The eldest son Cyril (1895-1983) served in the AIF 12th Battalion in France and Flanders during the First World War. After his return from the war, he was in business as a furrier and was an active member of the New Town Methodist Church.

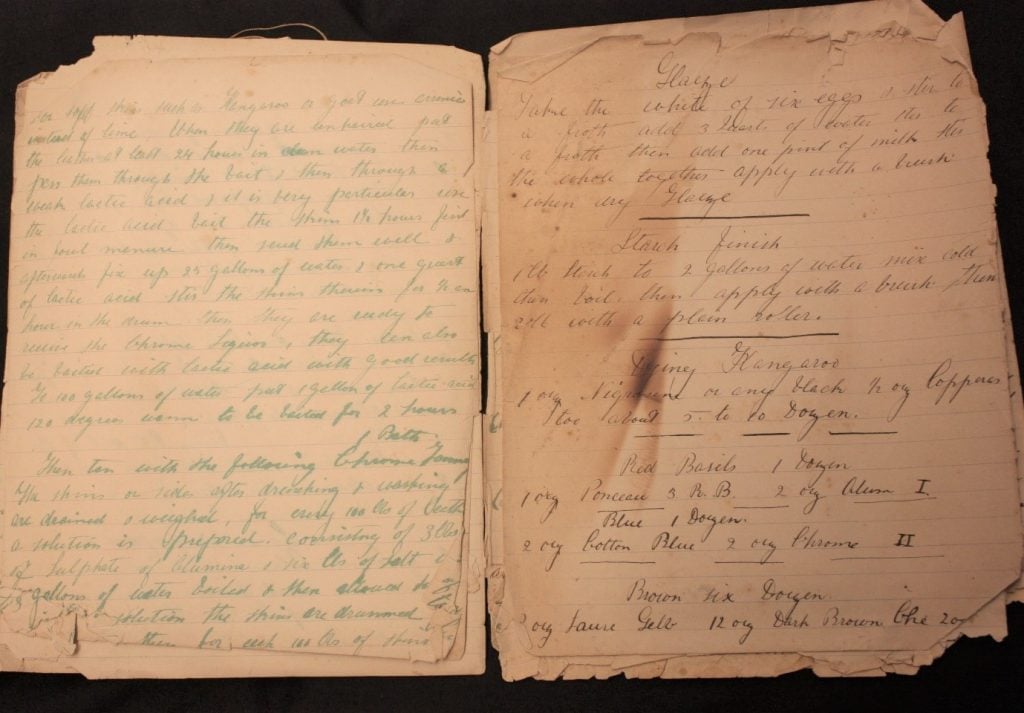

Cyril’s daughter Margaret donated a collection of family papers and photographs, including The Art of Dying and John Allen’s own handwritten notes on dyeing techniques, to the Tasmanian Archives in 2016.

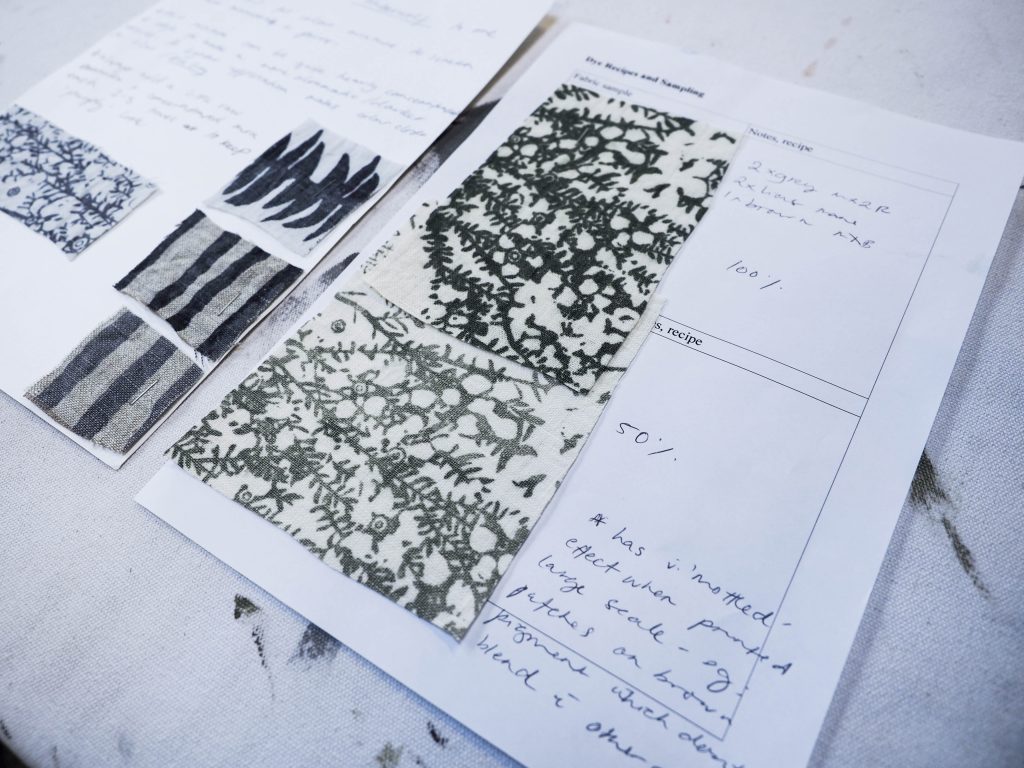

In 2019, contemporary Tasmanian textile artist Yolanda Zarins started experimenting with John Allen’s recipes. Yolanda writes:

I thought it would be interesting to compile parts of John Allen’s letters and recipes alongside similar notes of my own as I was struck by how similar the very specific experimental notes were despite the different methods used. The calligraphy script in Allen’s letters was really difficult for me to read, so I took the copies to my 90 year old grandmother in Smithton and she was able to read them to me. She noted the use of mutton bird fat in one recipe to soften the dyed leather; similarly, she would collect this fat during the mutton bird season to polish her father’s work boots. I asked how people coped with the smell and she didn’t recollect it being a problem – although she did say that care had to be taken not to leave the boots out overnight or they would be consumed by quolls or Tassie devils.

Further reading

Keith Adkins, Reading in Colonial Tasmania (2010)

Luke Agati, Strutting the Stage: Tasmanian Theatre in the First Twenty-five Years (2017)

T C Allen, Via Risdon Road (1985)

Bernard Bergonzi, A Victorian Wanderer: The Life of Thomas Arnold the Younger (2003)

Peter Crisp, ‘Hone, Joseph, 1784-1861’, Australian Dictionary of Biography (1966)

Christopher De Hamel, The Book: A History of the Bible (2001)

Joseph Foster, Alumni Oxoniensis: The Members of the University of Oxford 1500-1886 (1968)

Margaret Glover, ‘George Henry Peck b. c.1810’, Design and Art Australia Online, 1992 (updated 2011)

Marie Boas Hall, ‘Hellot, Jean’, Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography (2008)

Christopher Hill, The Experience of Defeat: Milton and some contemporaries (1984)

Mary Hoban, An Unconventional Wife: The Life of Julia Sorell Arnold (2019)

William Hone, Trial by Jury and the Liberty of the Press (1818)

Dianne Lawrence, Genteel Women: Empire and Domestic Material Culture 1840-1910 (2012)

Bernard C Middleton, A History of English Craft Bookbinding Technique (1996)

Kim Pearce and Susan Doyle, New Town: A Social History (2002)

Linda Porter, Royal Renegades: The Children of Charles I and the English Civil Wars (2016)

Lindy Scripps, The Industrial Heritage of Hobart (1997)

J B Hope Simpson, Rugby since Arnold (1967)

Blair Worden, The English Civil Wars 1640-1660 (2009)

Newspaper articles from Trove

‘The Late Mr Gellibrand’, Tasmanian News (Hobart) 26 Oct 1887, p.3

‘The Late Mr T. J. [sic] Gellibrand’, Tasmanian News (Hobart) 14 Nov 1887, p.2

Greetings!

I chanced upon the article concerning the musical collection of Mrs W Fletcher, Hannah, daughter of Joseph Hone, Lawyer and Public Servant, Van Diemens Land. It is most interesting.

Her daughter, Miss Margaret Fletcher was an accomplished singer whilst the musical ability flowed through to her grandson, Thomas Fletcher and to his grandson, Tom Fletcher (yours truly) plus my grandchildren.

I live in Queensland with my wife and I visiting Tassie a couple of times on holidays. In fact, we attended a small Fletcher Family (descendant) reunion in Tassie during the Tassie bicentenary celebrations and it was then, that we learned that Tassie Museum has some artificats of the Fletcher Family – William Fletcher’s oilskin coat, reputedly worn during the Peninsular Wars against Napoleon, plus William and Hannah’s granddaughter’s ball dress. Most interesting and so pleasing to see they are being preserved, rather than kept in a disused family trunk away in some attick.

Sincerly,

Tom Fletcher

Impressed by your research into these volumes and fascinated by the stories they tell (not least the interconnections between early colonial families and the tangled threads connecting VDL and Britain)

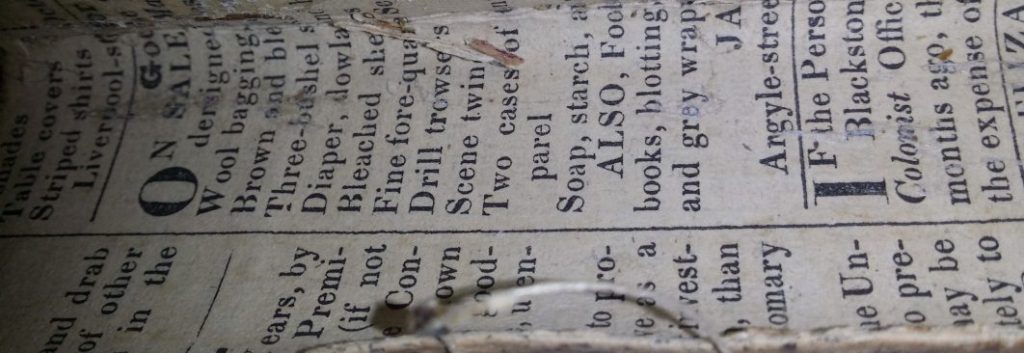

Re VDL book binders – while Peck’s establishment is a distinct possibility given that these volumes contain music, it is not the only one. Rolwegan actually arrived in Hobart in Feb. 1834 so cannot be ruled out. In July of that year both he and another bookbinder, George Howard, appear to have been working for Dr. Ross. By 1836 Howard was working for Peck but I’m not sure when he commenced there. Rolwegan stayed on with W G Elliston when Ross sold the Courier to him and the two bookbinders went into partnership in 1837. Another possibility is the binder who worked for Andrew Bent in 1834, Polish born London convict Ernest Elsmer. Bent acquired new book binding gear (along with presses and types) mid 1832. In the Colonist of 6 July 1832 Bent advertised that he had received the most modern ornamental tools and an assortment of coloured leathers. “Music and other fancy Books neatly bound in Morocco, and lettered in gold”

Hi Sally, thanks for your comments. Andrew Bent is an intriguing possibility, especially in view of Mrs Fletcher’s family connection with William Hone.