The Orphan Schools

This year marks the 150th anniversary of public education in Tasmania.

To help us understand where we’ve come from (and perhaps where we’re going!) the librarians and archivists of the State Library and Archive Service are producing a series of blogs on the history of public education in Tasmania. These aren’t comprehensive – rather, they’re snapshots of places, people, and institutions, as well as a guide to the resources we hold at the State Library. Some of the common themes that feature throughout the blogs are concerns about the curriculum; about health, physical fitness, and nutrition; about sanitation; about industrial training and academic outcomes. But these blogs are also something more – they’re about the history of childhood in Tasmania, and how our view of children – and what education means – has changed since the nineteenth century. We hope you enjoy the journey!

The Orphan Schools established in Hobart in 1828 were an early form of public education, but a harsh one. Their aim was to transform poor children into ‘respectable’ industrious adults. The system was cruel even by the standards of the day – based on discipline, religion, punishment and control. Most of the children were not true orphans, but the children of convict parents, whose imprisonment and work for the convict system prevented the parents from caring for them. Others were the children of the unemployed, destitute, or those that the authorities perceived to be leading immoral lives. Some Aboriginal children were institutionalised as well. All were separated from their parents, housed in cold rooms with no fires and poor sanitation; disease was rampant and mortality was high.

What follows is not easy reading, and it is not suitable material for young children. The story is characterized by cruelty, abuse, and neglect, but also by tremendous resilience, resistance, and compassion. The historical records in the Tasmanian Archives tell this story – and throughout this blog, we will link to them. You, the reader and researcher, can choose to follow the story further in as much in depth as you choose to.

The Origins of the Orphan Schools

The orphan schools were not the only form of education in the colony prior to 1868, but they are one of the best-known. The buildings themselves still exist in New Town, and their history is entangled with the family histories of many Tasmanians. That’s because the orphan schools linked the convict system with public education and social welfare. The colonial government (and many free settlers) feared that the penal colony of Van Diemen’s Land would always be a haven of vice – and thought the best way to prevent children inheriting the ‘stain’ of their parents was to remove them, discipline them, and reform them.

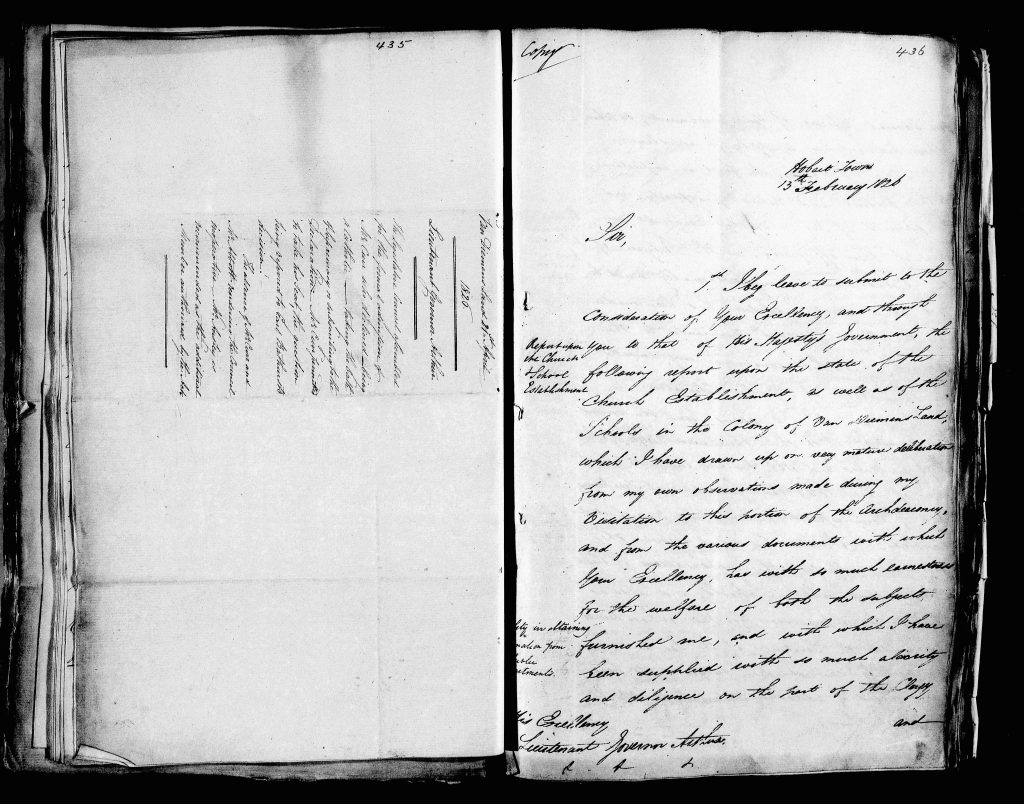

In 1826, Archdeacon Scott laid out a plan to Governor Arthur for a system of public education. He would remove children from their ‘dissolute’ parents (especially if they were convicts, unmarried, and/or poor) and train them in infant, primary and orphan schools around the colony. From the co-operation of church and state, Scott argued, there would be moral reclamation, and “a new race must spring up”.

At the same time, Governor Arthur ordered a survey of destitute and orphaned children in the colony (CSO1/1/122a, often known as the “Children’s Census”). Various ministers of religion and local magistrates reported to Arthur the children in their districts. In all, over 100 children were said to fit the criteria as being eligible for care in an orphan school. This number was to grow rapidly as the 19th century progressed. You can read more about this in our forthcoming blog, “Looking for the Lost Children” by librarian Elizabeth Lehete.

Who were the Orphans?

![An application form. Text reads: “Form of application for admission of children into the queens asylum for destitute children. Name of applicant- Rose Sheedy. Residence – left blank” A table shows names, dates of birth, by whom hospitalised when and where, and parents when where and by whom married: filled out information is as follows: “1. Emily Sheedy, 16.8.64, C Wood, Illegible. 2. Illegible, 18.5.69, C Wood, Illegible. 3. Edith Sheely, 15.6.71, C Wood, illegible” Text of additional information below reads: “Religion – Roman catholic. Name of father. Kenny Sheedy 38. Residence – Left the colony. Religion R C. Ship to the colony and date of arrival – Rodney 3rd. Whether arrived free or bond- Bond. Civil condition, free by servitude, Conditional Pardon, or ticket-of-leave- Illegible. Date of freedom or pardon – Blank. Trade or occupation – Illegible. Name of mother on arrival – Illegible. Residence – 33. Religion – blank. Ship to the colony and date of arrival - Roman catholic. Whether arrived free or bond- Bond. Civil condition, Free by servitude, conditional pardon, or ticket-of-leave- Illegible. Date of freedom or pardon- blank. How employed- Blank.” Text at the bottom of the page reads: “This application for the admission of the child named therein, of whom [parent of guardian] I am the is made with my sanction and at my request. Signature, witness. This should be signed by the father of the child. If his signature cannot be procured, the mother must sign it. Where it is impracticable to obtain either signature, the guardian or person having charge of the child is to sign.”](https://cdn.shortpixel.ai/spai/q_glossy+to_auto+ret_img/libraries.tas.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/SWD26-1-1P109-664x1024.jpg)

It’s important to remember that “orphan” in the early nineteenth century didn’t mean a child with no parents living. It was actually a very loose term, one that meant any child who was thought to be uncared for or destitute.

As the Hobart Town Courier laid it out in March 1828, children entered the orphan schools in four “classes” :

“1. Those who are entirely destitute

2. Those who have one parent living

3. Those who have both parents living… totally incompetent to afford their means of education

4. Children whose parents may be able to contribute re maintenance of 12 pounds.”

Admission was made by applying to the Governor. This was undertaken by the parent, guardian, or on advice from those in charge of the asylum.

Most of the children had parents who were convicts, and had arrived on the convict ships with their mother. There is now a sculpture on the Hobart waterfront, “Footsteps Towards Freedom” by Irish sculptor Rowan Gillespie to honour them. In general, children under the age of three were taken to the Cascades Female Factory with their mothers (being left in the care of other convict women if their mother was sent into assignment after the baby was weaned).

Not all of the ‘orphans’ came from convict families, however. For example, there were children of an agricultural worker of Old Beach whose house was burnt down and family left destitute; or the free settlers whose ship was wrecked on the way to Hobart. Some free parents paid money to the orphan school for the education of their children. Some children had unknown backgrounds, and were “orphans” as we would use the term today. Edwin Burns was “found wandering about in state of total destitution and had been in the bush for several years among the worst characters his father is dead and mother if any exists has totally deserted him.” There were also a number of Aboriginal children – survivors of the “Black War”, offspring of sealers and Aboriginal women, or those who had been living with white families. Research suggests approximately 20 Aboriginal children had been in the schools, including those sent away from Flinders Island.

Once inside the Orphan School, it was difficult to leave – especially when parents were desperate to bring their children home. This was because on entering the institution, the governor became the children’s legal guardian, and a committee would scrutinize the parents’ circumstances to determine whether or not they could care for their children. Many parents’ applications to bring their children home were refused. This was the case of William and Jane Davis. Both were convicts, and when they received tickets of leave, they wrote stating they could now care for their child. The authorities refused to release the child, but told the parents that they would now be expected to pay for their maintenance. Some parents defied the authorities. There is the case of a Mr Butcher of Bagdad who took his child out of the school on the pretence of buying him some shoes, never to return. Children regularly ran away, though they were usually captured, returned, and often beaten.

The School Buildings

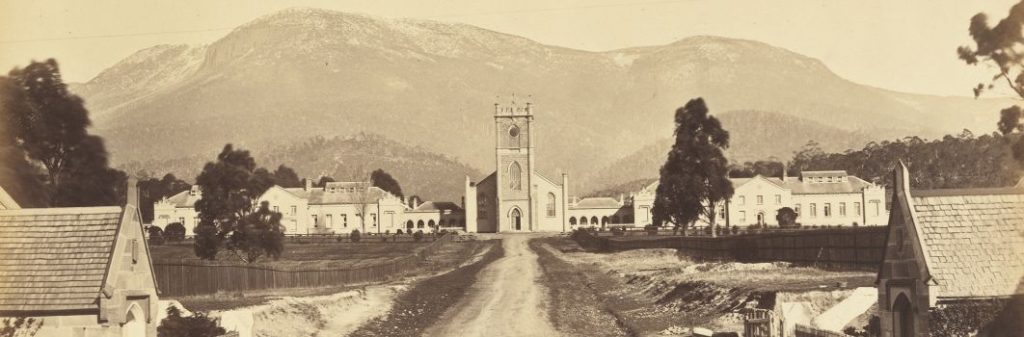

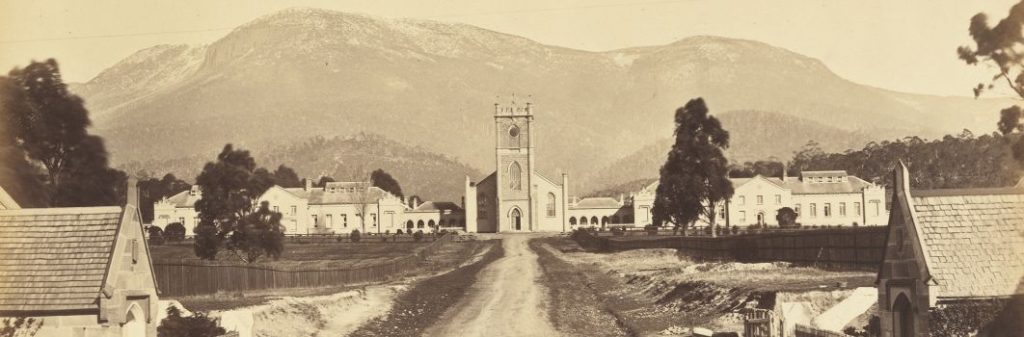

Originally, there were two orphan schools – one for boys at the Constantina Distillery on the New Town Rivulet (established in 1827), and one for girls at Belle Vue in Davey Street. From the very beginning it was clear that the buildings were unsuitable. They were badly overcrowded – at the Boy’s Orphan School, two or three children shared a bed, and the school room itself was hung with hammocks, which were removed before the start of lessons. A report in December of 1828 recommended a new building with two school houses, “each … with its outhouses, yard, garden and ground… effectively detached from the other, and its appendages as to prevent so far as practicable, the children of one [gender] from mixing with those of the other.” To keep the numbers down, children were sent out to work as servants to reduce the numbers.

The new school took five years to complete. This structure, designed by architect John Lee Archer still stands today at the top of St John’s Avenue, and it was opened in 1834. A church was incorporated in the design for both inmates of the schools and the parishioners of New Town, and it became central to the whole community: free, convict, and orphan. But the different classes were kept separate – galleries and screens worked to keep the orphans separate from the choir, the prisoners and the public. Occasionally when the parishioners closed their eyes in prayer they would have still been aware of their fellow congregation members by the outbreak of insect infestations on the church pews.

Life Inside the Orphan Schools

In April of 1839, the Colonial Times reported on life inside the new Orphan Schools:

“Everyone knows how pleasing an appearance the exterior of the building exhibits; we wish we could say as much of the interior; but this we cannot do, as the majority of the apartments allotted to the use of the children, are cold, comfortless, and ill arranged upon a most mistaken system of parsimonious economy…. In one room we saw five little fellows blue and shivering with cold, there was it is true a fireplace in the room, but no fire…We have seen many assemblages of children in our time, both at home and abroad but never did we see two hundred human beings, that exhibited so squalid an appearance, as did the majority of the Queens Orphans.”

The Orphan School. (1839, April 23). Colonial Times (Hobart, Tas. : 1828 – 1857), p. 4. Retrieved March 22, 2019, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article8749624

In 1848, a report by the Inspector of Schools, Charles Bradbury documented how little had changed. At this time the Superintendent was Charles O’Hara

Booth who had formerly been in charge of the establishment for boy convicts at Point Puer.

Bradbury reported how infants slept three to a bed in a separate compartment. The elder inmates were divided by religious denomination and slept in hammocks. They stayed in the dormitories from 6.00 in the evening, until 5.00 o’clock in the morning. This routine was extended an hour during summer months. On visiting the dormitories Bradbury noticed tubs at either end behind screens. At night the inmates were woken to use these primitive facilities – “ the children nestled in their warm, close hammocks are roused always with difficulty – they get out staggering and in confusion, and naturally with almost surmountable reluctance and vexation, chilled and shivering with the cold…notwithstanding this practise the beds are wetted…”

The boys were issued with three suits, two made from moleskin and the third, a Sunday suit of blue cloth. These suits were made by female convicts on the convict hulk HMS Anson, as the material was “too stubborn for the strength of the boys’ fingers”. Their shirts were made by the girls of the institution. The girls made their own dresses and wore bonnets made on the Anson. Unlike the boys, the girls wore socks inside their ill-fitting shoes. Clothes were recycled to the younger inmates as the older ones grew out of them.

Governor Denison and the Comptroller General John Hampton both concluded from Inspector Bradbury’s report that the system was defective and that the children “had lost the elastic spirit of youth.” Denison stated that the children “…are cut off from the indulgence of all these feelings and sympathies which are connected with the relations between parents and children.” Hampton, while he thought religious education was crucial, also thought it had to be done correctly. The children shivering in church on cold mornings did not bring “a sentiment or love of God.”

Hampton was alarmed by the children’s physical development, stating that they were inferior “to other children of the same class.” He put this down to the lack of exercise. He suggested starting a garden, cultivated by the children, with the produce to be sold to the town’s greengrocers and the proceeds going towards the children’s maintenance. He also suggested that the best students be enrolled in the neighbouring Normal School to undertake training for teaching at the Orphan School. Some of these changes were introduced over the following years, but the Normal School was abandoned within 2 years, closing in 1851.

“I have deserved it when I have been beaten. It has not left black marks upon me with the blood almost bursting out. I have never seen any other girls so beaten. I am happy here. I get enough soup.”

Sarah Ann Jessop, 1859

It was an open secret that the Orphan Schools were rife with abuse. There were numerous commissions and inquiries into conditions, many of which documented severe beatings, neglect, and systemic abuse. These records make for very difficult reading, but it’s from them that we get a few of the voices of the children themselves – though they testify to a bleak existence in which some were willing to endure violence in exchange for food and shelter. These records can be found in the correspondence of the Colonial Secretary’s Office, the Meetings of the Committee of Management, the Tasmanian Parliamentary Papers, and other sources – there is a partial list under “Further Reading” at the end of this blog.

Dr. Edward Swarbreck Hall was also crucial in documenting the abuses at the Orphan School. He was a medical and sanitary reformer who acted as a watch dog for nearly two decades between the 1850s and 1879 when the school closed, interviewing children, inspecting conditions and taking administrators to task.

Education

The curriculum at the Orphan School consisted mainly of rote learning and the 3Rs – reading, writing, and arithmetic. Two afternoons a week were set aside for religious instruction. The inmates also attended church daily. In 1848, Inspector Bradbury was not impressed with what the children had learned. One wonders whether this had more to do with his questions than with the children’s learning – according to Bradbury, none of them could explain the meaning of self-denial nor where Jamaica was located. He gave the children two days to compose an essay on the subject “the advantages of being industrious” but no one wrote a line.

Some children worked under a shoemaker, tailor and baker employed by the institution. The girls did plain needlework and some were able to knit. Laundry work, aside from bedding which was taken to the Cascades Female Factory, was undertaken by the girls. To keep the costs down, many children were employed as domestic servants and attendants to the teachers, which took up a great deal of their time. Bradbury criticized this system in 1848, concluding that the girls weren’t prepared for any future beyond the institution – they were “not qualified for respectable service, except merely as nurse maids, nor trained as wives in the labouring man’s home, or even the judicious provision and preparation of his frugal meals… [they are] ignorant of rural life.”

The resilience of the students – and their determination to learn – under these conditions was astonishing, and many did go on to become heads of households, respectable citizens, and leaders in their communities – and you can read about their stories in Dianne Snowden’s . Voices from the Orphan Schools: the children’s stories. Some of the Aboriginal children who left the Orphan Schools went on to become powerful advocates for their community – men and women like Walter George Arthur (who organized the first petition of indigenous people in the British Empire to Queen Victoria in 1846, documenting the abuses of Dr Jeanneret at Flinders Island) and Fanny Cochrane Smith (who received a land grant, raised a large family, and fought until her death to preserve Aboriginal culture in Tasmania – recordings of her voice are the only records we have of Tasmanian Aboriginal songs).

Fox’s Feast

The Fox’s Feast was an event that brightened the often bleak year of the children of the Orphan School. John Fox was a waterman who had plied his trade on the Derwent for decades, and he left a bequest to the Orphan School children when he died in 1859. Fox had not been a former inmate of the institution, but was an orphan when he was transported as a boy. “His bequest should be appropriated to the benefit of the children in the institution and not to that of the government or the government or the maintenance of the establishment ….he wished all the children to have a feast after they attended his funeral.” Thus the appropriately named Fox’s Feast was born.

There is at least one contemporary account of Fox’s Feast from 1872. On the 13th of February, in what is now known as the Cascade Gardens, 350 children were given meat, pastry, ginger beer and fruit. The children (who had to march from New Town to Cascades and back again to get their treat) were able to revel in the sunshine and the beauty of the gardens for a few hours, fill their bellies, play games, and listen to music. The bequest of John Fox is still legislated in some form to this very day.

The Closure of the Queen’s Orphan Asylum

By the late 1860s, the number of children entering the Queens Orphan Asylum began to decline, owing to a new system of outdoor relief, the introduction of the boarding-out system, and the establishment of industrial schools and the Public Education Act. This decline in numbers saw the closure of a building constructed in 1862 specifically for infant children. In 1874 it was utilised as a charitable institution for women. By March of 1879 arrangements were underway to close the orphan school with the remaining children sent to other institutions such as the Boys Home in Lansdowne Crescent and the Catholic orphanage, St Joseph’s, in Harrington Street. You can read more about the circumstances of the closure of the Orphan Schools in CSD10/1/70/1717.

Further Reading & Resources:

Digitized Primary Sources:

SWD6/1/1: Register of Children admitted and discharged from the Infant School, 1851-1863

SWD7/1/1: Daily Journal of Admissions and Discharges to Queens Orphan Schools, 1841-1851

SWD26/1/1: Applications for admission and associated papers, 1862-1874

SWD27/1/1: Register of Applications for Admission, 1858-1879

SWD32/1/1: Register of Children Apprenticed from the Asylum, 1860-1886

Secondary Sources and Guides:

Kim Pearce and Susan Doyle. New Town: a social history. [Hobart, Tas.] : Hobart City Council, 2002.

Inquiries and Investigations:

1831 enquiry into Robert Giblin, first head master at the Boy’s Orphan School, who beat a 14 year old boy to death: The gruesome facts of the case, and the testimony of the boys can be found in CSO1/1/122/3073, CSO1/1490/10836 and SWD24 , all of which you can read on microfilm in the Reading Room in the Hobart Library.

1859 inquiry into Matron Harriet Smyth and her misappropriation of food and ill treatment of the children: Tasmanian Parliamentary Papers 1859 Paper 72

1874 enquiry into the brutal beatings administered by the acting superintendent J.M. Graham ( who was dismissed): CSD7/1/61/1499

Websites and further Research Resources:

Libraries Tasmania Research Guide: Life as a Child in Care

Thanks for this comprehensive overview of the Orphan Schools. I’m interested in the Management Committee as it operated in the 1830s. I believe both Rev. William Bedford and Rev. Philip Palmer were amongst its members and they were known to be in active and acrimonious dispute at that time. Also, the secretary of the Committee was a George Everett, who seemed to sprout an M. D. qualification along the way. He later acted in medical capacities at New Norfolk, Port Arthur and Norfolk Island. You mentioned the Meetings of the Committee of Management, implying there are existing records of that Committee, but I’m not finding them. Are such things actually available through the Archives?

Hi Lee, we are glad you have found this helpful. The records of the Management Committee are Tasmanian Archives series SWD24: https://stors.tas.gov.au/AI/SWD24

These can be viewed at the State Library and Archives building, 91 Murray Street, Hobart.

Thanks Jess, but it appears these only cover to 1832… nothing after that?

Lee

this is a very informative story on orphanages, my grandmother was at Newton about 1925.and after she died her husband put the two boys and two girls in the home, then went back to the west coast to work. He had 3 more children.

I feel very unhappy for what he did, I know that they were different times then.

Thank you for sharing the information however many of the links to the primary sources are broken – is it possible for someone to fix the links? Thank you.

Thank you so much for alerting us to the broken links, Heather! We’ve done some updates to the library catalogue in the last six months and some items needed to be re-linked. We are really grateful to you for catching the error, and everything should work properly now. Thanks!

Thanks for sharing the history of the former Orphan Schools in New Town. Here is some information about the current use and recent ‘history’ .

Since 2008 Kickstart Arts has worked with the Department of Health to repurpose the buildings and establish the Creative Living Park in recognition of the positive health outcomes and community engagement Kickstart’s art and cultural programs offer as an adjunct to DoH services, in particular those operating from the site. This is an exciting initiative that expands the possibilities for arts, health and community partnerships as well as providing a long term solution to the ongoing maintenance and care of these extraordinary old buildings. For more information about Kickstart Arts and the creative programs being run at the former orphan school – now named the Kickstart Arts Centre go to website: https://www.kickstartarts.org/

or facebook: https://www.facebook.com/kickstartartstas/

Thanks for this most interesting and informative article. Great links to related resources