The Great Comet of 1843

…the ladies complain that their husbands are in the habit of starting from their sleep, shouting, “Have you seen the Comet?”

For five weeks, from 1st March 1843, the night sky of Tasmania was ablaze as the most spectacular comet seen since 1680 unexpectedly appeared. Initially mistaken as an aurora, the comet’s tail soon became visible, and people were enthralled. The phenomenon was not mentioned in British newspapers until about three weeks later. The Southern Hemisphere proved to be the best vantage point, however there were no cameras. It was a year before the oldest known photograph in Australia was taken, but people from Glenorchy to King Island put pen to paper to record this astronomical event.

George Hull (c. 1786 – 1879)

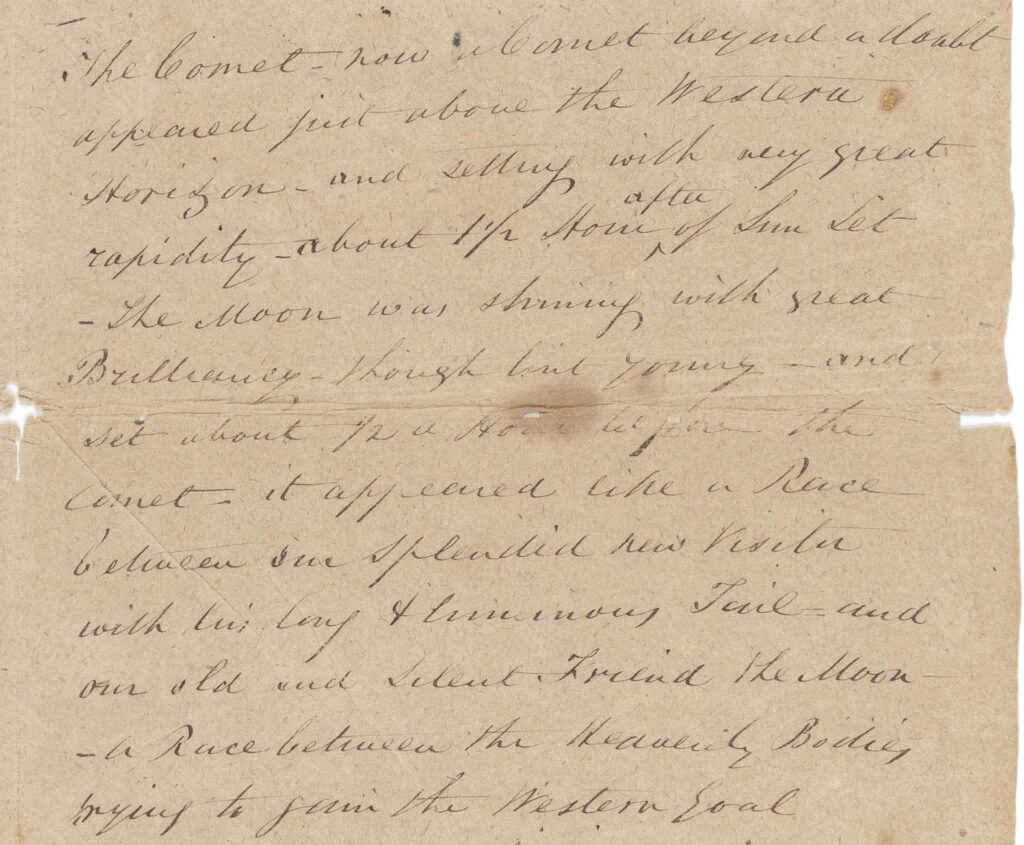

One such person was George Hull, a farmer from the property ‘Tolosa’ (now the site of Tolosa Park, Glenorchy). His original diary pages that include his account of the comet were donated to the Tasmanian Archives earlier this year (NS7882-1-1) by his great great granddaughter, author, Lucille V. Andel.

As George Hull recorded the mundane daily tasks of farming – such as repairing the bullock cart and harrowing and rolling turnips – something caught his eye. On Friday 3rd March 1843, he wrote “I slept at Bradburys last night – luminous appearance in the sky”.

The next night it became clearer what he was seeing, he wrote, “saw tail of comet first time – & said twas a comet”. By Monday 6th there was no doubt:

The comet now a comet beyond a doubt appeared just above the western horizon and setting with very great rapidity about 1 ½ hour after sun set. The moon was shining with great brilliancy – though but young – and set about ½ a hour before the comet. It appeared like a race between our splendid new visitor with his long & luminous tail – and our old and silent friend the moon – a race between the heavenly bodies trying to gain the western goal…

On Wednesday 8th March, George commenced sketching the comet. He writes and sketches the following:

Not visible to night from the heavy & dark clouds that obscured the western sky after sun set – but at 10 o’clock – saw a considerable part of its splendid train – very bright & not diminished in splendour nor apparently in length… contrary to my idea last night it does not appear to have much changed its course – or verged more towards the west & north – the part of the train or tail visible to night stretches almost as before over Good Friday Hill thus

On Saturday 11th March, George sketched a series of images to capture the comet’s trajectory. He wrote –

Sky clear – not a cloud to hide it from head to tail – it appears to stretch its train full one fourth part across the heavens – as far as they are visible from horizon to horizon. It seems to me to point about N.E. and is evidently moving in towards the north – when first seen after sun set it was at a considerable height above the north-west part of Good Friday Hill – behind which it dipped exactly at 20 minutes past 8

High winds again nearly all day with squalls and showers …

… appearance of the tail of the comet at 10 o’clock …

… supposed inclination before setting …

… Can’t make it out Oh! For mathematics and astronomy –

George’s final mention of the comet is on Friday 17th March, he reports of the comet, “Thursday – very pale – and barely visible owing to the brilliancy of the full moon. Friday – very cloudy night – not visible at all.”

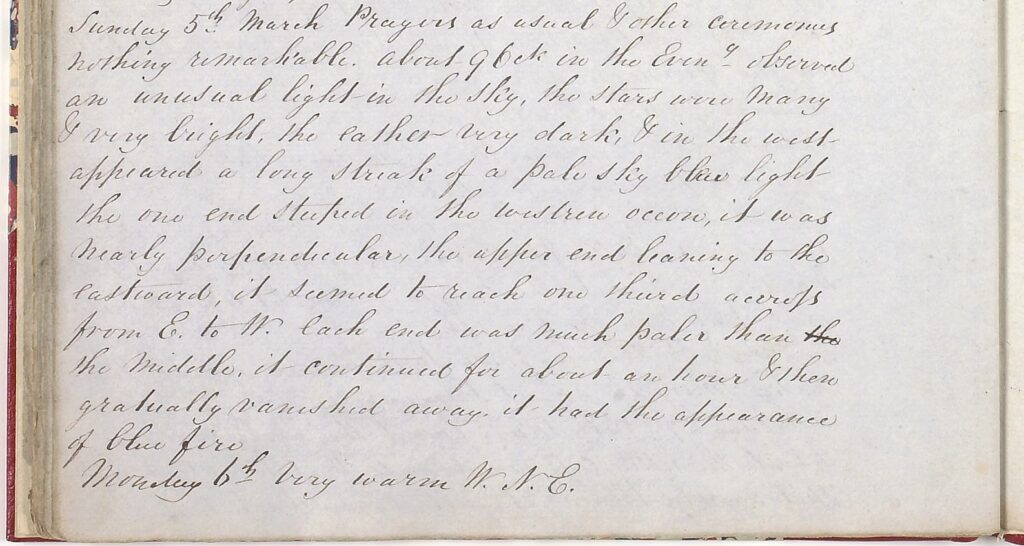

John Scot / Scott (c. 1780s – 1843)

John Scott (or Scot – his surname is variable) lived on King Island and kept a journal (NS1612). Like George in Glenorchy, John was, at the time, occupied by agricultural concerns. A plague of grasshoppers had destroyed thousands of potato, cabbage and turnip plants. Yet John’s eyes were also drawn to the remarkable phenomenon in the sky. On Sunday 5th March he wrote:

Prayers as usual and other ceremonies, nothing remarkable. About 9 o clock in the evening observed an unusual light in the Sky, the stars were many and very bright, the eather very dark. In the west appeared a long streak of pale sky blue light, the one end steeped in the western ocean it was nearly perpendicular, the upper end leaning to the eastward, it seemed to reach one third across from E. to W. Each end was much paler than the middle. It continued for about an hour and gradually vanished away. It had the appearance of blue fire.

Joseph Henry Kay (c. 1815 – 1875) Captain, R.N., Royal Magnetical Observatory, Hobart Town

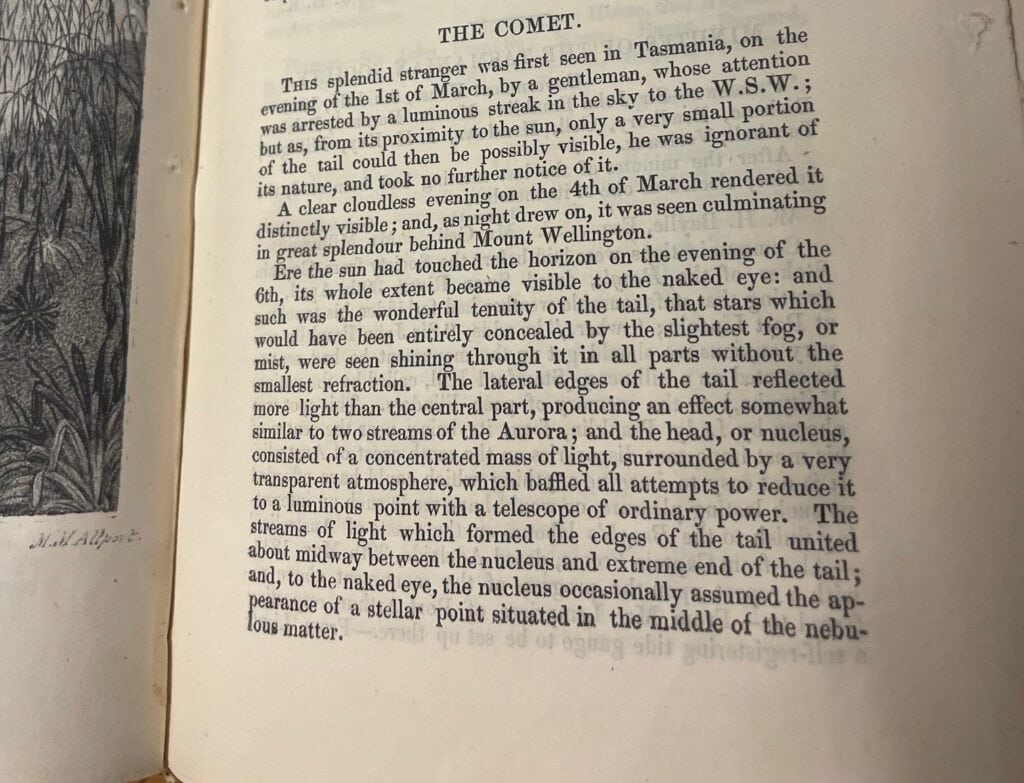

George Hull and John Scott weren’t the first to spot the comet. According to Joseph Henry Kay in his 1846 article ‘The Comet’ published in the Tasmanian journal of natural science, agriculture, statistics, etc:

This splendid stranger was first seen in Tasmania , on the evening of the 1st of March, by a gentleman, whose attention was arrested by a luminous streak in the sky to the W.S.W.; but as, from its proximity to the sun, only a very small portion of the tail could then be possibly visible, he was ignorant of its nature, and took no further notice of it. A clear cloudless evening on the 4th March rendered it distinctly visible; and, as night drew on it was seen culminating in great splendour behind Mount Wellington.

Mary Morton Allport (1806 – 1895)

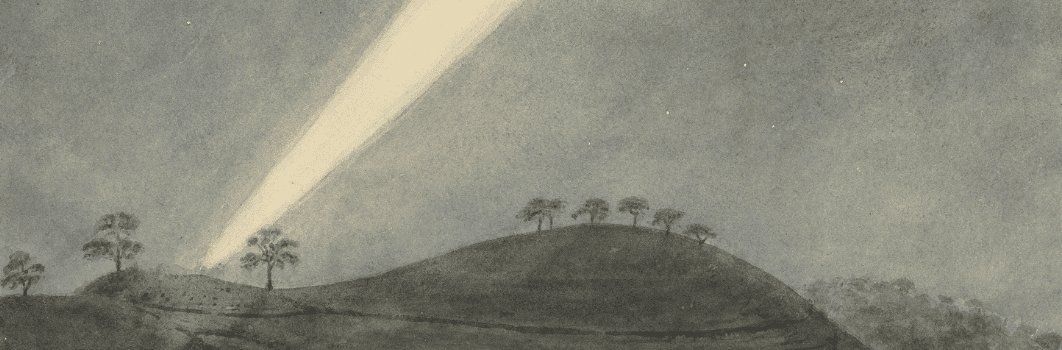

Published alongside Joseph Henry Kay’s article was an image of Mary Morton Allport’s lithograph, Comet of March 1843 : seen from Aldridge Lodge, V.D. Land.

Mary Morton Allport, widely regarded as the first professional female artist in the Australian colonies, sat on the balcony of her home to sketch the historic event. Originally from Staffordshire, she had lived in Van Diemen’s Land for 12 years at that point and was at her creative peak, before her eyesight began to fail.

Her original, striking monochrome lithograph is held in the State Library and Archives of Tasmania’s Allport collection.

Mary sent her lithograph to the London Illustrated News, which published it the following year, stating they were “indebted to a Staffordshire correspondent…the scene has been effectively lithographed by Mrs Allport”.

Allport was among the first artists to produce Tasmanian lithographic prints, a technique discovered in 1798 and widely adopted after the 1820s. Lithography appealed to both artists and printers because it allowed them to create images on stone with the same ease as drawing on paper.

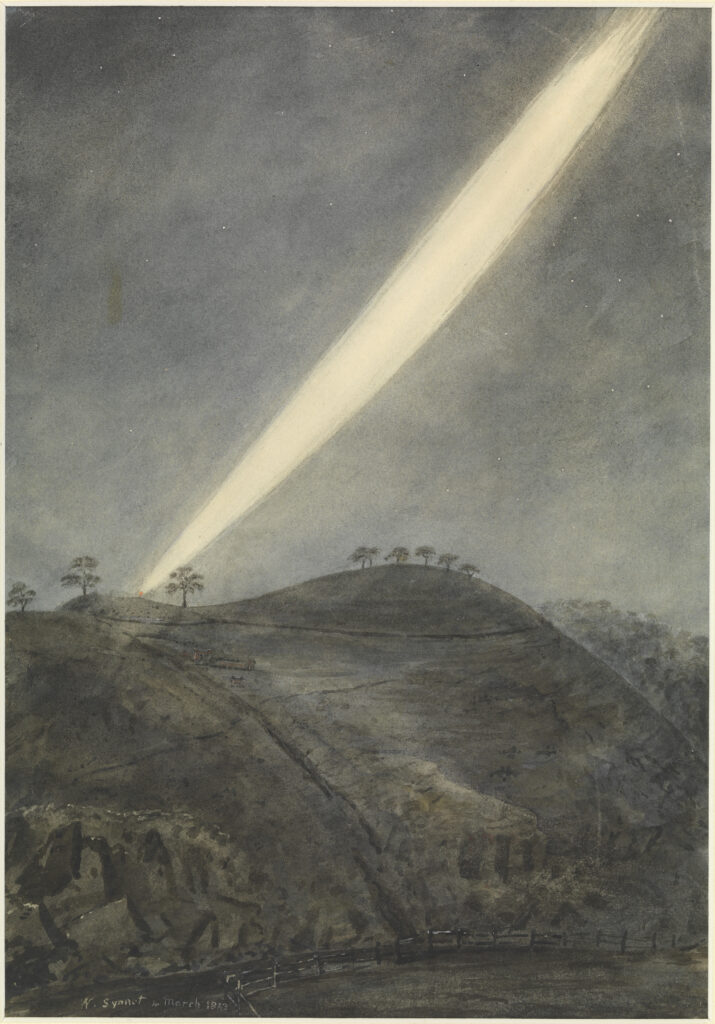

Walter Synnot (1773 – 1851)

Artist Walter Synnot made his career in the British Army. He became an ensign in the 66th (Berkshire) Regiment of Foot in 1793 and was promoted to the rank of captain. In 1836 Walter (then aged about 63), his third wife Mary Jane and eight of the children from his second marriage emigrated to Tasmania.

While much of his work was dedicated to botanical illustrations, he too painted the 1843 grand astronomical event. He completed the work at or near his house in Canning Street, Launceston. He inscribed the back of his watercolour with the following notes:

“Sketch of a comet as it appeared on the evening of the 4 March 1843 7 o’clock pm bearing nearly west from Launceston Van Diemen’s Land. The body of the comet was set before 8 o’clock pm. The tail formed an angle of about 60 degrees from the plain of the horizon and was of astonishing brilliancy. The view is a part of the Cataract Hill from Canning Street.”

Newspaper accounts

At the time, newspapers described the spectacle as “One of those mysterious and, in the estimate of some weak-minded persons, portentous phenomena, comets, has been whisking its fiery tail for several nights past in our hemisphere.”

The article went on to describe how unexpected the astronomical event had been, catching many off guard. It stated:

“to the evident alarm and surprise and amazement of many more, since no mention is made in WHITE’S Ephemeris or in the Nautical Almanack for the present year of the probable appearance of such an erratic wanderer, or of the predicted return of one whose period of revolution is ascertained…Much less were our fellow-Colonists prepared to receive so unexpected a visit from a celestial meteor, whose approximity [sic] to our earth is considered, by vulgar minds, to presage all sorts of bad omens…”

THE COMET. (1843, March 4). South Australian Register

Other articles took comfort in knowing that the comet had been seen across the whole globe, to have:

“their observations upon it, of the scientific men of England and of other countries. For ourselves we must plead a very superficial knowledge of Comets, or other bodies which appear in the heavens, and be excused from offering an opinion of our own about the present phenomenon, which naturally causes so much interest.…the largest of all Comets then seen, appeared in 1680, and is calculated to reappear in the year 2254.”

The Comet. (1843, March 11). The Cornwall Chronicle

And indeed, there was a certain amount of shame and embarrassment in the astronomical community for failing to predict the event. On 21st March 1843 editors wrote:

“Murray’s Review affirms for a fact, that the comet is now visible…and blames the observatory people at Hobart Town, for not giving timely notice of its intended appearance. The Review ought not to omit in its censure all the other astronomers in the world; they are equally culpable with our Van Diemen’s Land friends.”

Local, (1843, March 21), The Hobart Town Advertiser

The comet loomed large in the conscious and subconscious minds of the community and was a hot topic of discussion. Many letters were written to the newspapers about it. At the end of March, editors wrote:

The Comet appears to be the engrossing topic of conversation, the different papers teeming with letters addressed to the Editors from private individuals, anxious, it would seem, to afford to their less enlightened brethren some knowledge of the mysteries of this interesting phenomenon…

…the ladies complain that their husbands are in the habit of starting from their sleep, shouting, “Have you seen the Comet?”

PORT PHILLIP. (1843, March 31). The Courier

Global Phenomenon

Artistic depictions and vantage points varied widely across the globe. Astronomer Charles Piazzi Smyth captured the view of the comet from the Royal Observatory, Cape of Good Hope, South Africa:

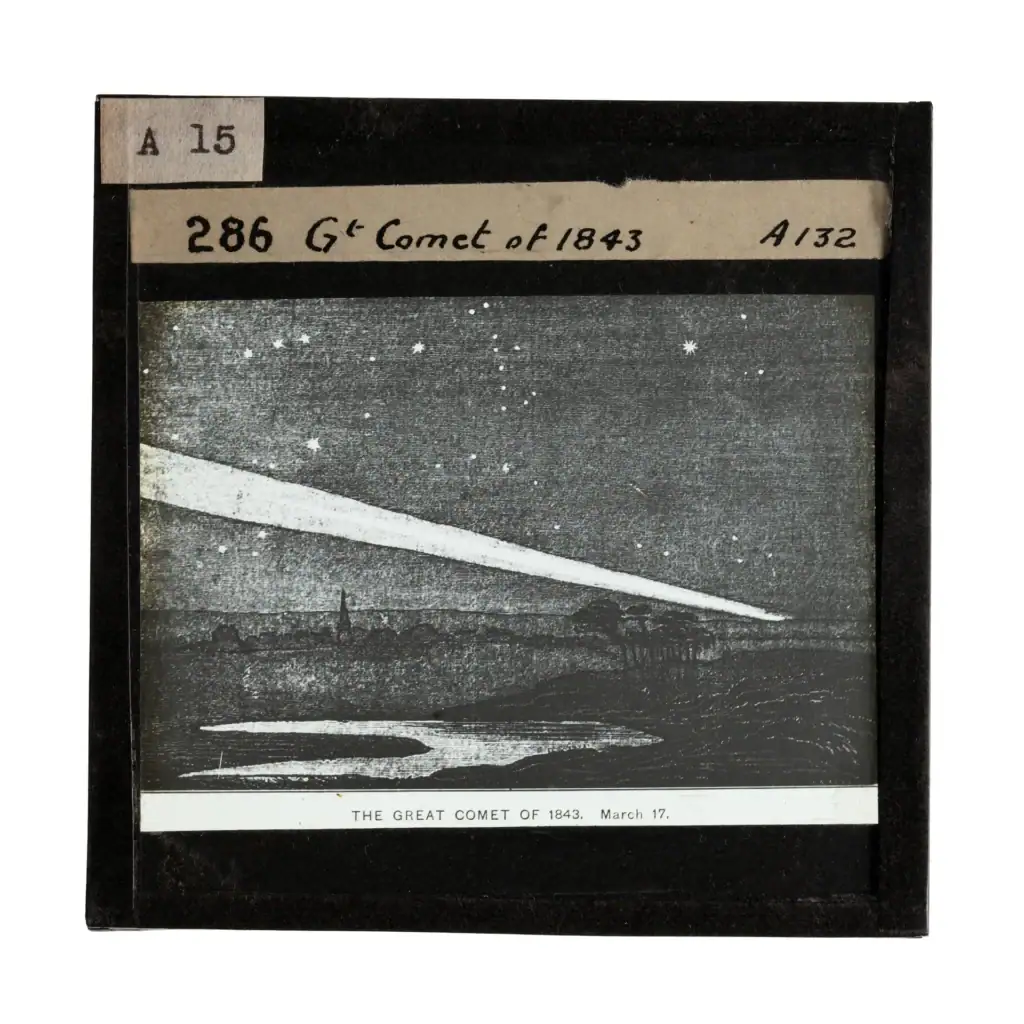

As the Great Comet of 1843 has become known as one of the most spectacular comets in history, it isn’t surprising that images of it have been used to educate people about astronomy. An example is the lantern slide below, used as an educational tool at the Sydney Observatory in the early to mid-twentieth century:

From 1843 to the present

George Hull’s diary pages and sketches were inherited by a grandson, John Lock Munro Hull who, perhaps inspired by his grandfather’s account, co-founded the Astronomical Society of Tasmania in 1934. The diary pages were then passed on to his distant cousin Lucille V. Andel for safekeeping. Our sincere thanks to Lucille for transcribing these pages back in 1989, and for then donating the original pages to the Tasmanian Archives this year.

To bring the story of the Great Comet full circle, we asked the Astronomical Society of Tasmania to tell us more about the science underlying this event.

The Great Comet according to the Astronomical Society of Tasmania

The Great Comet of 1843, which has a formal name of C/1843 D1, must have been a magnificent sight, even in daylight hours. In fact, the name Great Comet is only given to comets that are exceptionally bright. It was discovered in February of 1843 when it became visible as it approached the Sun.

For those not familiar with comets, they are a body of ice, dust and rock with a radius of tens of kilometres that were left over from the birth of the solar system. As a comet approaches the Sun, an atmosphere of gas develops, called a coma, and sometimes a tail of gas and dust is blown out from the coma which can extend up to 15 times Earth’s diameter. These phenomena are due to the effects of solar radiation (i.e. heat) and a continuous stream of charged particles called solar wind plasma. Nearly all comets orbit the Sun and have elliptical (egg-shaped) orbits. The orbits of comets range from just beyond the planets to half way to the next star.

What we know about the Great Comet of 1843 is that it passed very close to the Sun at a distance of 827,000 kilometres which is closer than any other object observed up until that date. The close proximity of the Sun caused a long tail due to the substantial disruption of the coma. The tail was measured at about 300 million kilometres long which is twice the distance from the Sun to the Earth. Also, the vast amount of material released by the comet as it passed the Sun meant that the comet and its tail were very bright due to the massive amount of reflected light.

The comet was easily visible in daylight, as evidenced by the sketches and paintings of the time. Only the very brightest celestial objects, such as Venus and the Moon, are visible in the daylight. The comet came closest to the Earth 6 March 1843 at a distance of 120 million kilometres and was at its brightest the following day. The best views of the comet were from the southern hemisphere, hence the widely published sketches and paintings from Tasmania and South Africa.

There are various estimates of the amount of time for the Great Comet of 1843 to return past the Sun, but most are in the range of 600 to 800 years. So unfortunately, we won’t see it again in our lifetime.

I am sure the astronomers of today would love to get the opportunity to observe first-hand a comet like the Great Comet of 1843.

Can you add to this story?

Do you have any records that document the great comet of 1843? Or perhaps other astronomical events in Tasmania? The Tasmanian Archives would love to add to our collections in this area so please get in touch via our collections offer form or email communityarchives@libraries.tas.gov.au.

References

- Earl, C. & Riley, M. (2020, October 31). From daguerreotypes to glass plates: Australia’s oldest images – photo essay. Retrieved from The Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2020/oct/31/from-daguerreotypes-to-glass-plates-australias-oldest-images-photo-essay

- State Library and Archives of Tasmania, Hull Family (NG300), Diary – George Hull’s account of the Comet of 1843 (NS7882-1-1)

- State Library and Archives of Tasmania, John Scott (NG1612), Copy of journal by John Scot [Scott] recording details of his life on King Island with Mary and

Maria, Aboriginal women (NS1612-1-1) - Joseph Henry Kay in his article ‘The Comet’ published in the Tasmanian journal of natural science, agriculture, statistics, etc. Vol. II (1846), p. 155-156

- Comet of March 1843 : seen from Aldridge Lodge, V.D. Land / Mary Morton Allport (SD_ILS:91720), lithograph, Allport Library and Museum of Fine Arts, State Library and Archives of Tasmania

- “The Illustrated London News.” Illustrated London News, 3 Feb. 1844, p. 80 – Gale Primary Sources

- Rowse, D. (June 2011) Captain Walter Synnot and his book of Cape plants and flowers, University of Melbourne Collections, Volume 8, 27-31

- Sketch of a comet as it appeared on the evening of the 4 March 1843 7 o’clock pm bearing nearly west from Launceston Van Diemen’s Land / W. Synnot (SD_ILS:80077), watercolour on paper, Allport Library and Museum of Fine Arts, State Library and Archives of Tasmania

- THE COMET. (1843, March 4). South Australian Register (Adelaide, SA : 1839 – 1900), p. 3. Retrieved September 19, 2025, from Trove

- The Comet. (1843, March 11). The Cornwall Chronicle (Launceston, Tas. : 1835 – 1880), p. 2. Retrieved September 19, 2025, from Trove

- LOCAL. (1843, March 21). The Hobart Town Advertiser (Tas. : 1839 – 1861), p. 2. Retrieved September 23, 2025, from Trove

- PORT PHILLIP. (1843, March 31). The Courier (Hobart, Tas. : 1840 – 1859), p. 4. Retrieved September 19, 2025, from Trove

- Royal Museums Greenwich. (n.d.). The Great Comet of 1843. Retrieved from Royal Museums Greenwich

- Charles Piazzi Smyth, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons File: Smyth The Great Comet of 1843.jpg – Wikimedia Commons

- Warner, B. (1980). The Great Comet of 1843. Monthly Notes of the Astronomical Society, Southern Africa, Vol. 39, 69

- Powerhouse Collection. c 1900-1950, Lantern slide used at Sydney Observatory. Retrieved from Powerhouse

- Scientific background of the Great Comet of 1843 provided by the Astronomical Society of Tasmania, Sept 2025

Thank you for a fascinating article. I have forebears ( McDowall and Garrett) who lived in Bothwell at the time. They must have observed this.

Hi Rosie,

Thank you for your message. The comet was apparently very hard to miss – so I am sure they did. Hopefully some of your forebears kept diaries or correspondence that records their observations of this time.

Rachael Gates

Archivist