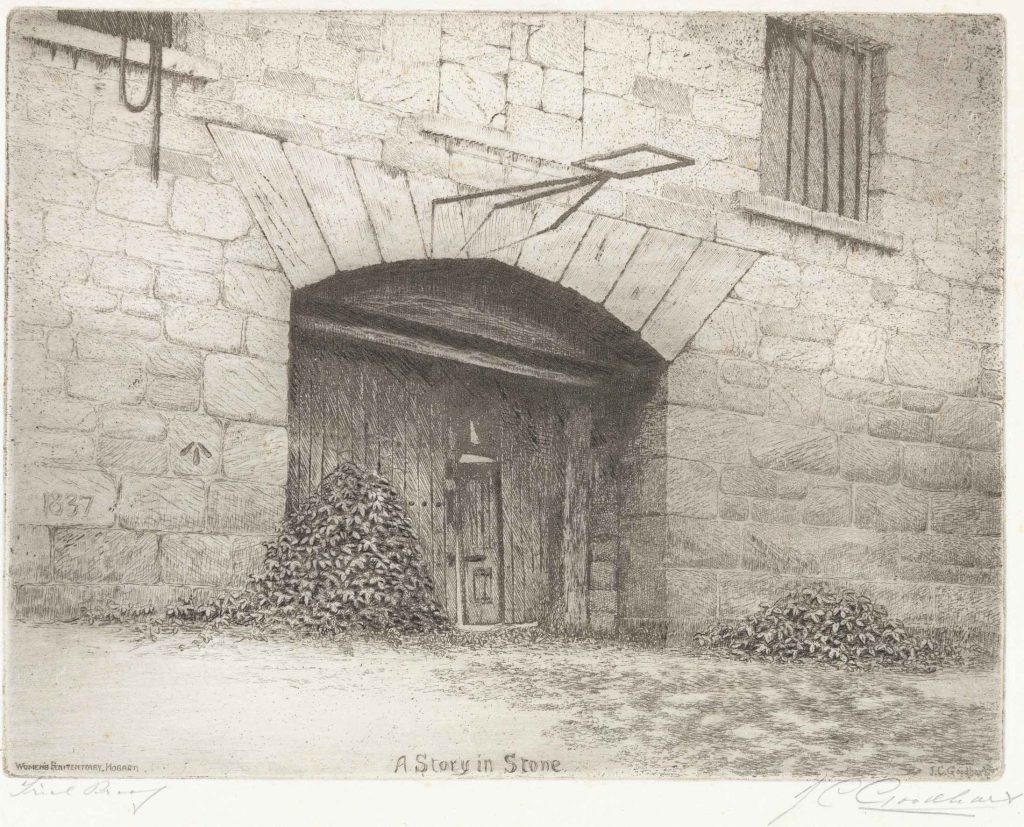

Esther’s Story, Part Three: The Cascades Female Factory and Brickfields Invalid Depot, 1870-1877

In 1870, a horrific assault took place at the Cascades Female Factory. At eight o’clock in the morning on the 13th of July, a woman named Eliza Osborne beat an elderly woman named Ellen Conway with the iron dinner bell. She hit her in the head so hard that the bell cracked. Ellen Conway was a 73 year old ex-convict who had been sent to the depot for begging. One of the people who rushed to her side to help her was the nurse, Mrs Cecilia Eliza Paul. A few kilometres away (about 25 minutes’ walk), the nurse’s daughter ten year old Esther Mary Paul was also a witness – to her uncle George’s marriage at the family home at Cross Street, Sandy Bay.

This week in Esther’s story, we break away from the whaling logbook where we first found her as a five year old girl. Now we’ll trace her and her parents through two institutions which housed the most vulnerable people in Hobart in the 1870s – the Brickfields Invalid Depot and the Cascades Establishment. To piece that story together, we have to jump forward and backward in time a little bit, but I promise it is worth the journey!

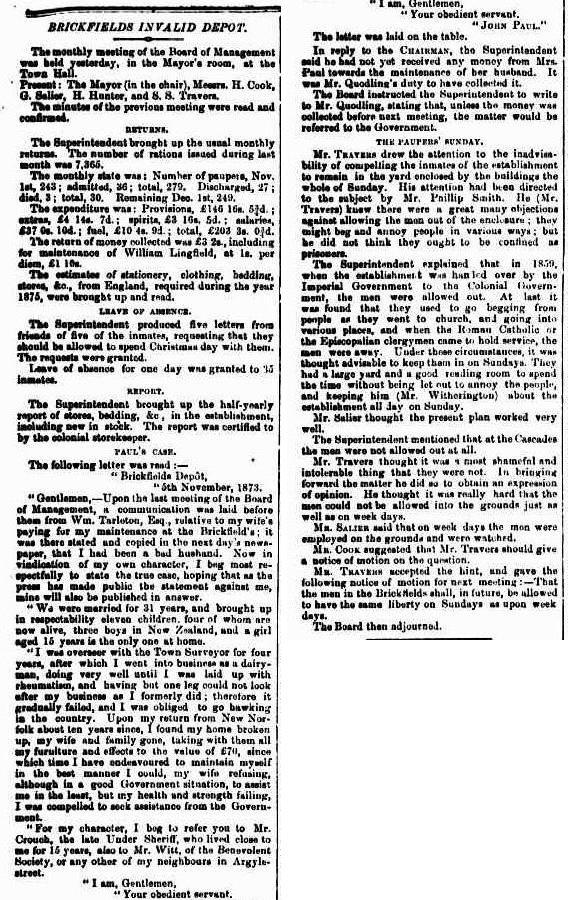

‘The Maintenance of a Husband’: Cecilia and John Paul go to war, 1873

A few weeks ago, I was idly searching through Trove at about 11 pm (the common lot of the curious insomniac). I don’t remember which of Esther’s parents I was looking for, but I stumbled across them both. It was a letter from December, 1873, written by John Paul. He was inside Brickfields Invalid Depot, defending himself from accusations made by his wife Cecilia in the newspaper that he had been a bad husband. What he wrote sheds light not only on Esther’s young life, but also on her teenage years, and how her two parents came to be on two different sides of an institutional wall – one an inmate, and one a keeper.

In his letter, John Paul claimed that he had been married for 31 years, that he and his wife had had eleven children (seven of whom had died, and three of whom had emigrated to New Zealand). One teenage girl – Esther? – was left at home. He went on, making the case that he was a respectable family man, but had been abandoned by his wife around 1863, and fallen on hard times as a result:

“I was overseer with the Town Surveyor for four years, after which I went into business as a dairyman, doing very well until I was laid up with rheumatism, and having but one leg could not look after my business as a I formerly did; therefore it gradually failed, and I was obliged to go hawking in the country. Upon my return from New Norfolk about ten years since, I found my home broken up, my wife and family gone, taking with them all my furniture and effects to the value of 70 pounds.”

John Paul, “Paul’s Case: Brickfields Invalid Depot.” The Mercury 04 December 1873: 3.

Was this the same John Paul? The dates seemed to match, and yet other things didn’t – he had signed his own marriage record with a cross, so I couldn’t understand how he could have worked with the Town Surveyor, still less have written this letter. But the claim to be a dairyman fit with his occasional profession as a “cowkeeper.” Then there were the number of children – I couldn’t find birth records for eleven children (but an eagle-eyed reader of an earlier blog, Robert Poole, has! See his comment on Part Two). But John Paul had Esther’s age nearly right, and he referenced living in Argyle Street – and most of all, the dates seemed to match, especially the crisis in 1863. According to John Paul’s letter, “I have endeavoured to maintain myself in the best manner I could, my wife refusing, although in a good Government situation, to assist me in the least.” He was forced, he said, to seek relief in the Brickfields Invalid Depot in New Town – a place that was seen by many as the place of last resort.

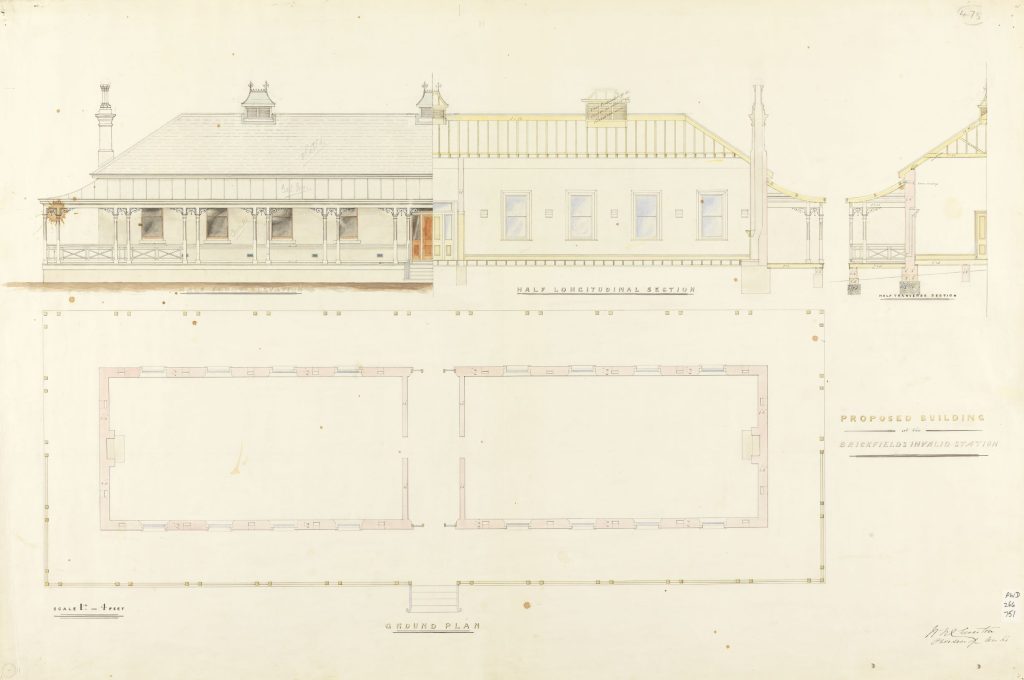

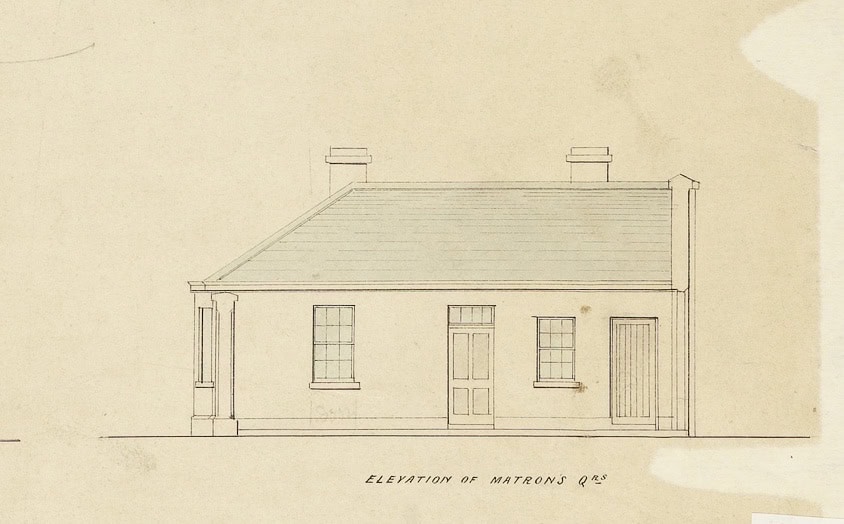

PWD266/1/751: Plan-Brickfield Buildings, Hobart. Architect, W.H.Cheverton, Overseer of Works, 1870

In Poverty Is Not a Crime, Joan Brown wrote that many of the “respectable poor” like John Paul “declared they would rather starve in the streets than be admitted to the Institution (105).” Those who ended up at Brickfields were at the end of the line – chronically ill, elderly, and “with a total lack of relatives willing (or compellable) to support the applicant.” Most of the men there, Brown writes, would have been “friendless ex-convicts” or “the immigrant who had not had time to build up a network of family ties (Brown, 122-123).” When he arrived, Esther’s 66-year old father would have been stripped, searched, and placed into institutional clothes (Piper, “Mind Forg’d Manacles,” p 1049). Any money he had would have been taken off him. Their lives were regulated, Andrew Piper writes, by the sound of a bell, marking when they were to rise, when they were to wash, and when they were to eat. The same was the case at Cascades – where that bell became an instrument of violence as well as of discipline on a July morning three years earlier.

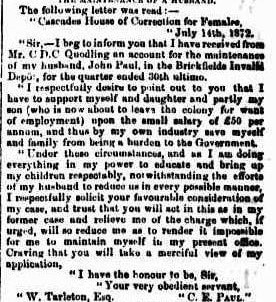

That brings us to Cecelia’s letter, written almost two years to the day after Ellen Conway was nearly beaten to death with the dinner bell. On 14th July, 1872, Esther’s mother wrote to the administrators of Brickfields that she had received a bill for her husband’s maintenance. He had been in Brickfields for at least the three months that was generally allowed. She flatly refused to pay. “I am doing everything in my power to educate and bring up my children respectably,” she wrote, “notwithstanding the efforts of my husband to reduce us in every possible manner.” The police magistrate, William Tarleton, was sympathetic. On the one hand, Mrs Paul was being paid 50 pounds a year, plus housing and board, and she “should be in a position to pay something,” he wrote. That said, “on the other hand, the man has been a bad husband to her, and she has been maintaining herself and her family for years by her own exertions.” Considering that she was a “good and trustworthy public servant,” she should be given some leeway, and pay as little as possible towards the maintenance of the man who had abandoned her.

These are astonishing letters – but I am especially struck by that reference to the education of her children. Was Cecilia thinking of the whaling logbook where Esther wrote her lines as a five year old in 1860? Is it evidence of that struggle to hang onto respectability, using every means within the family’s power, and every scrap of paper to stay above poverty line? Cecelia’s letter, of course, leads to more questions. It implies that Esther was at Cascades with her, and it begs the question – how long had Cecilia been at Cascades? Was Esther with her or not? If so, were they living on site or nearby? And what had happened to the multigenerational household at Cross Street?

The Cascades Nurse: Cecilia Eliza Paul, c. 1868 – 1877

If you’re walking beside the Hobart Rivulet on a cold winter morning, feeling the icy breath of the mountain rushing down the valley and directly down the back of your neck, spare a thought for all those people who lived, laboured, and died at the Cascades Female Factory. This is where Esther seems to have spent some of her teenage years, while her mother Cecilia Eliza Paul worked there as a midwife and a nurse. Cecelia was unlikely to have had any specialized training (trained nurses weren’t employed in the General Hospital until 1876) and indeed, her only qualifications were likely to have been her respectability, her middle-age, and her status as a matron. What Esther did, and whether she even crossed the threshold of the institution, we cannot know. But we can put together something of her mother’s life, and how she came to figure in the lives of so many others who found themselves inside the stone walls of Cascades.

Both the Cascades Female House of Correction, where Cecilia Paul worked, and the Brickfields Invalid Depot, where her husband was interned, were part of the same late nineteenth century institutional system. In it, convicts, invalids, and the poor were on the same plane: people to be kept apart from respectable people, who needed to be reformed and remade behind walls. The fear was that poverty and ‘infirmity’ led to vice, and that vice could be spread like a disease to others who were precariously perched on the boundary between respectability and dissolution. John Paul’s case, as he stated it in his letter to the newspaper, was exactly what administrators were afraid of – a respectable family man and a shopkeeper who had slipped, had fallen through the cracks, and who was now dependent upon the government. Cecilia Paul’s case was that her husband had tried to drag her out of respectability too, but that she had clawed her way out, bringing her daughter with her.

Sometime around 1868, though perhaps before, Cecilia Eliza Paul took a job at the Cascades Female House of Correction as a nurse and a midwife. I know that she was at Cascades by 1868 because she was listed on an inquest in 1868 – one that Colette MacAlpine found in her research into inquests in the Female Factory (see Repression, Reform and Resilience, p 81).

Having lived in Hobart for 26 years, Cecilia would have known the reputation of the institution (see our earlier blog). The nursery where she worked was marred by infant mortality – in some years, more than a third of the babies who were born there died. Cecilia was no stranger to this, having lost seven children of her own. Esther was her only surviving daughter. Whether or not that made her more or less sympathetic to the women and babies under her charge, we can’t know. She had been struggling for years to avoid the very cliff that awaited so many women whose husbands abandoned them. But whether that experience hardened her heart or opened it, we cannot tell.

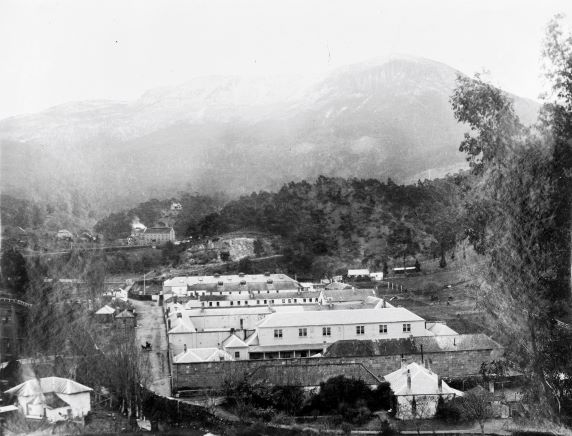

The Cascades Establishment (also known as the Female House of Correction) was a different institution by 1870 than it had been just two decades earlier when it was the Cascades Female Factory. Between 1828 and 1856, it was a place of secondary punishment for convict women. But in 1856, after the end of transportation, the introduction of Tasmanian self-government, and an 1855 inquiry into the substandard conditions (to put it mildly), the institution shifted its focus. Instead of housing convict women and their youngest children, the re-named Cascades Establishment would house a number of different institutions to house a wide section of Hobart’s underclass – from criminals to the poor, from prostitutes to the mentally ill, and pregnant women and their babies. It’s not impossible that John Paul might have ended up there himself. To learn more about it, check out Repression, Reform and Resilience: A History of the Cascades Female Factory.

As the nurse and midwife at the Establishment, Cecilia would have been in charge of the chronically ill and the elderly, mainly ex-convicts who ended up in the invalid ward (Alison Alexander, 175). She was also in charge of the babies and young children, sometimes (according to the newspaper) up to 60 at a time, all crammed together in the cold, forbidding place. She worked alongside prisoners, who had been given what some considered a plum position. When Martha Hill died in 1868, one of the other witnesses (along with Cecilia) was Jane Turn, both a nurse and a prisoner (MacAlpine, p 81).

We don’t know for sure when Esther joined her mother at the Factory, but I suspect that it was around 1872, when Esther’s grandmother died and left the family home to Esther’s uncle George. The whole household broke up around that time. Esther’s older brother headed to New Zealand, according to their mother. William and Charlotte Jacobs moved out to New Town, where William became the operator of the Augusta Road Toll Booth (see below). Esther, perhaps, joined her mother – because certainly by 1872, her mother wrote that she was supporting Esther by herself.

In 1874, when Esther was fourteen, a visitor to Cascades described it as a grim, cold, and overcrowded place. The hospital and nursery were paired with the dairy, which contained seven or eight cows to provide milk for the children. One can’t help but wonder if Esther, whose father was a “cowkeeper” when she was very little, ended up in the dairy for any length of time, but I rather doubt it. As the visitor described it, “The occupants are either the children of prisoners, foundlings, or the offspring of young mothers who are there with them, and callous fathers who are not…. The children all look healthy and happy, and do credit to Mrs. Paul, the head nurse, who has the superintendence of them.”

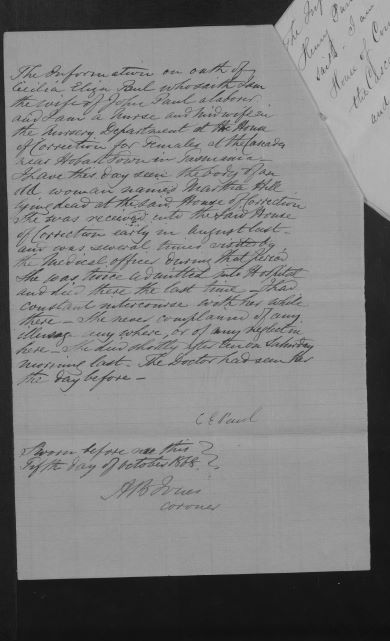

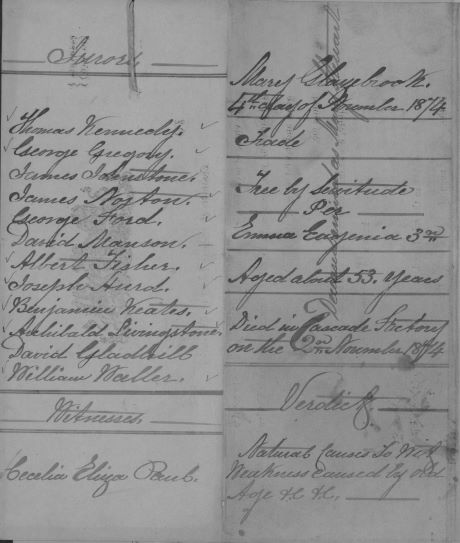

Mrs Paul had heavy responsibilities. She appeared often at inquests, such as this one in 1874 into the death of another aged woman, Mary Glaisbrook. Colette McAlpine and others have shown how incredibly useful these inquest records can be in painting a picture of life at the Factory – and we have indexes from 1828-1927 incorporated into the Tasmanian Names Index (though unfortunately you can’t search by witnesses!)

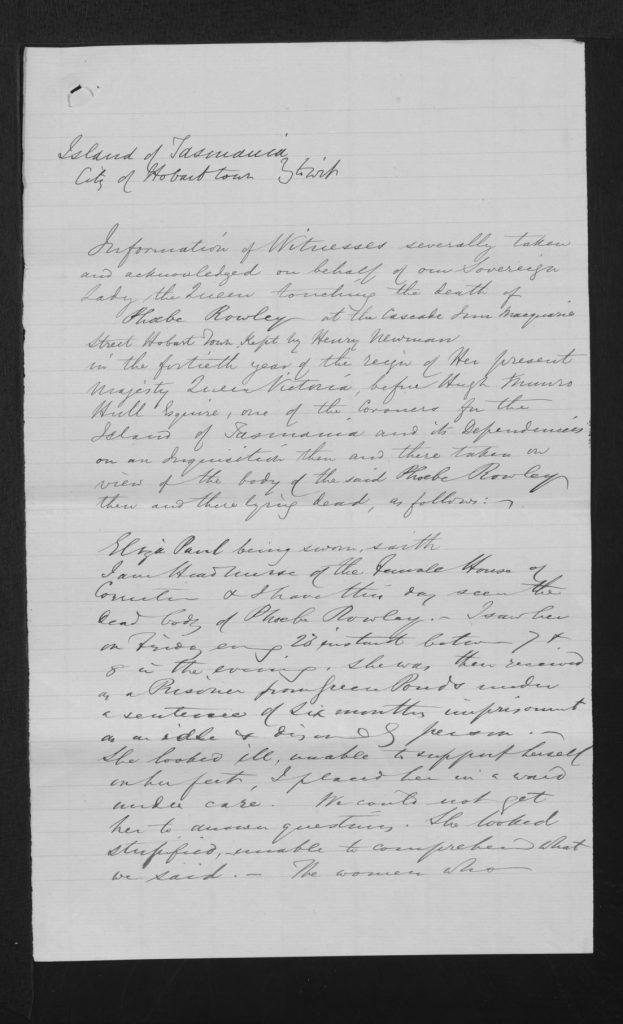

Inquest into the death of Phoebe Rowley, 28 February, 1877. Testimony of Eliza Paul, Head Nurse at the Female House of Correction. AGD20/1/2/6223, Tasmanian Archives

How long were Esther and Cecilia living in (or near) Cascades? I haven’t been able to find out definitively when they left, or even that they lived onsite (though the fight over John Paul’s maintenance in 1873 indicates that they were given food and housing). I know that Esther’s mother was still there by 1877, when she gave evidence in another inquest, the death of a prisoner named Phoebe Rowley from apoplexy, a 31 year old woman who left behind two little children, whom Mrs Paul sent to the Orphanage. This was just a year after the Female Factory had been condemned as a “complete bog” by the architect Henry Hunter, who wrote, “I endeavoured to sink holes in several places, but failed on account of water rushing in when only about two feet below the surface (quoted in Brown, Poverty is Not a Crime, p. 98).”

In 1877, the Cascades Establishment closed and its inmates were scatted to other institutions, before it was put to a new purpose as an asylum. We don’t know what happened exactly to Cecilia and then-seventeen year old Esther as the institution changed. But it’s possible that they might have returned to Cecilia’s sister, Esther’s Aunt Charlotte Jacobs.

The Augusta Road Toll Booth

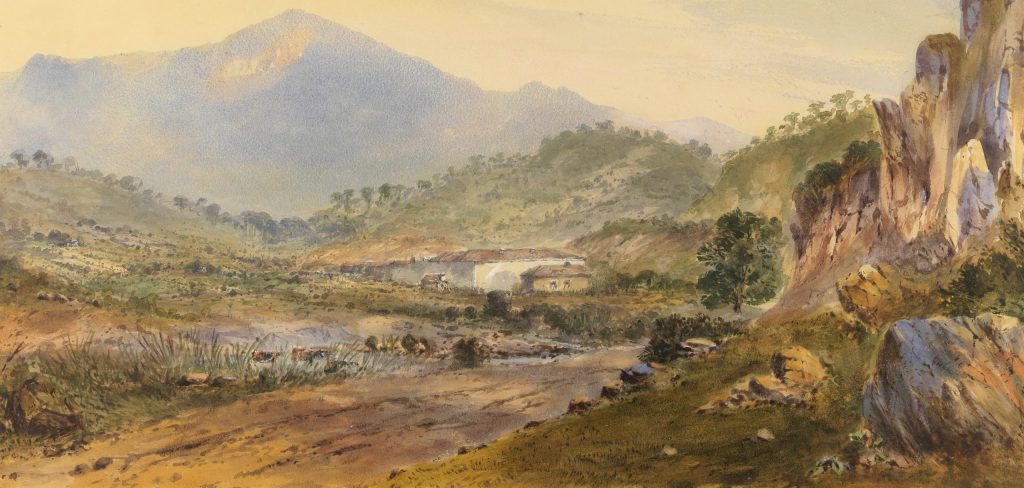

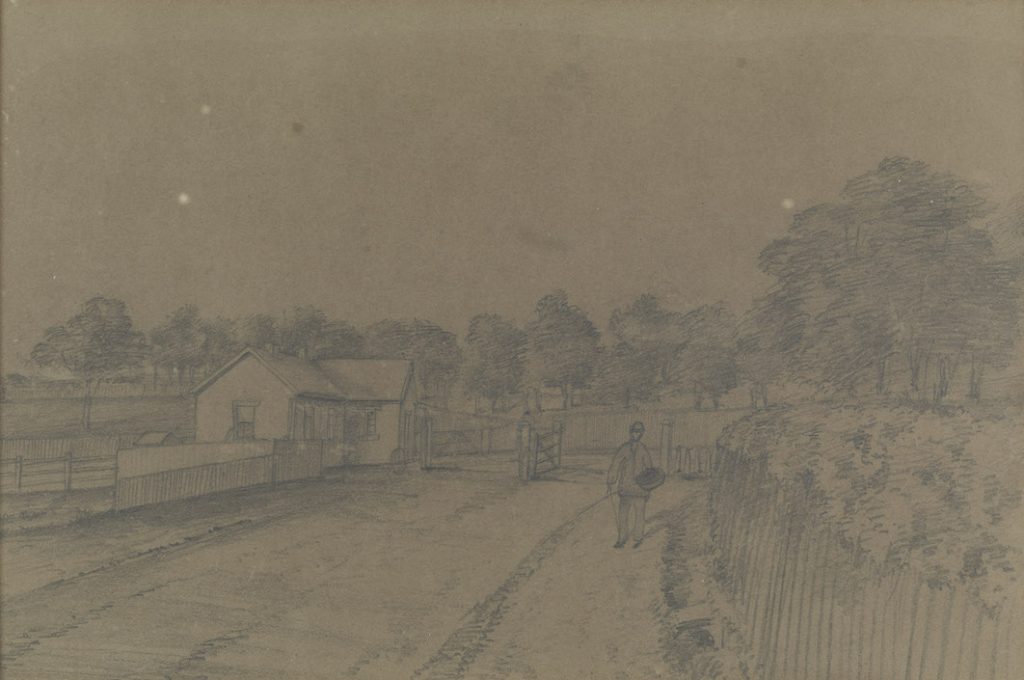

At the same time as she drew the Brickfield’s Invalid Depot in 1865, Miss Shoobridge also sketched the Augusta Road Tollbooth. Less than ten years later, both places would harbour members from the same extended family. While John Paul was at Brickfields, the Jacobs family – Captain William Jacobs and Charlotte Rowland Jacobs – had taken over management of the Augusta Road Toll Booth. In January of 1873, William Jacobs was appointed postmaster at the Toll Booth. He and Charlotte were only a few minutes’ walk away from Brickfields. A little over thirty years later, when the toll bar was removed, an article in the Mercury reminisced about how “at this spot, fees were exacted from drivers before they were allowed to pass on, and strange stories are told of the different methods of evading payments.” Four years after they took over the toll booth, Captain Jacobs died of cardiac disease, at 59 years old, in January 1877. A few days later, his widow Charlotte took over the job as postmistress.

Cecilia was still at Cascades in early 1877, for she was present at an inquest at the pub at the end of February, but when the establishment wound down, did she and Esther rejoin Charlotte? Did they move in with Cecilia and Charlotte’s brother in Sandy Bay? Or did they end up elsewhere? Did Cecilia stay on at Cascades as a nurse, or even as a matron when the institution became an insane asylum? At this point, I do not have those answers. But what I do know is what happened in 1880 – Esther got married.

In Hobart, Esther married at the age of 20 to John Henry Lithgow on May 11, 1880, in the Free Presbyterian Church in Hobart. He was a young chemist. The young couple immediately moved to Launceston and began having children. Their daughter Vera was born in February 1881, their first son Harry in 1884, and their second son Vincent in 1886. For the story of their life together in Launceston, and Esther’s tragic early death, please tune in next week for the final chapter (really!) in Esther’s Story.

Further Reading:

I spent a lot of time cross-referencing newspaper articles in Trove with our digitized inquests for this piece. The inquests are invaluable sources of information, but the tricky thing is to find them. They’re digitized and incorporated into the Tasmanian Names Index, but you can’t search them by the names of the witnesses or jurors. The best thing to do is to search in Trove first, and if you find a likely case reported in the newspapers, then you backtrack and see if you can find the full report on the website. Need help? Just ask us. You can always file a free research request and we can spend up to an hour doing research for you.

You can discover a great deal about the lives of convict women from the Female Convicts Research Centre. You can find them online here: https://www.femaleconvicts.org.au/

Also check out these excellent sources, which were invaluable in preparing this blog:

Lindy Scripps and Audrey Hudspeth. The Female Factory historic site, Cascades : historical report. [Hobart, Tas. : Dept. of Parks, Wildlife and Heritage], 1992.

Dear Anna, what a fascinating and compellingly-written tale! Did you ever publish the final chapter of Esther’s story? I am invested now! 🙂

Hi Philippa, Anna has moved on from Libraries Tasmania to work on her publishing career. She has since published one book, which is now out (https://libraries.tas.gov.au/Record/Library/SD_ILS-1424822) and I believe has another one in the works.

Unfortunately for us this means that Esther’s story remains unfinished. However, if Anna ever finds the time to return to this story, we will happily publish it.