Two forgotten bushranger plays

For more than 200 years, bushrangers have captured the imagination of storytellers and audiences alike. Their exploits have inspired songs, books, and, of course, plays. Read on to find out more about two forgotten bushranger plays that span the centuries and the globe, from the floorboards of the Royal Coburg Theatre in London to the airwaves of Tasmanian radio.

The bushranger is a central figure in Australian folklore. In the early years of penal settlement, convict shepherds were able to range freely in the bush. As some of them turned to robbery, the word ‘bushranger’ became synonymous with ‘bandit’ or ‘highwayman’. By the time Ned Kelly (son of an Irish transportee to Van Diemen’s Land) told Judge Redmond Barry that he would ‘see you there where I go’, 19th-century Australian bushrangers had acquired the dark, ambiguous glamour of 17th-century Caribbean pirates: defiant of authority, sometimes overtly political, living by their wits in an alien environment, often driven to crime by injustice or desperation, they commanded both fear and admiration.

Michael Howe (1787-1818) and Martin Cash (1808-1877) embody two contrasting stereotypes of the bushranger: Howe the violent sociopath, Cash the chivalrous rebel. Of course, the truth has more shades.

Howe was cruel and ruthless, and he terrified people. But the government of his day was cruel and ruthless too. In year that Howe was killed, British troops executed Ceylonese ‘rebels’ without trial; the following year, a peaceful protest in Manchester was crushed by armed cavalry. Howe’s adoption of the title ‘Lieutenant-Governor of the Woods’ implies a vision of an alternative government like the Caribbean pirate republic a century earlier.

As for the gentlemanly Cash: after avoiding execution for the murder of a policeman, he became a brothel-keeper in New Zealand. Later in life, he returned to Hobart and settled on an orchard at Glenorchy. His cottage still stands, and the orchard is now being revitalised by its new owners.

Howe’s atrocities, and his own gruesome death, were recounted in the optimistically titled Michael Howe: the last and worst of the bushrangers of Van Diemen’s Land (Hobart, 1818). Cash lived to publish his autobiography, The adventures of Martin Cash (Hobart, 1870). Both books are Australian classics and have been published in numerous editions (we have the original editor’s manuscript of The adventures of Martin Cash, and you can read it online here).

Howe and Cash were also the subjects of two very different plays, unique survivals of which are held in Libraries Tasmania collections.

The first play about Tasmania

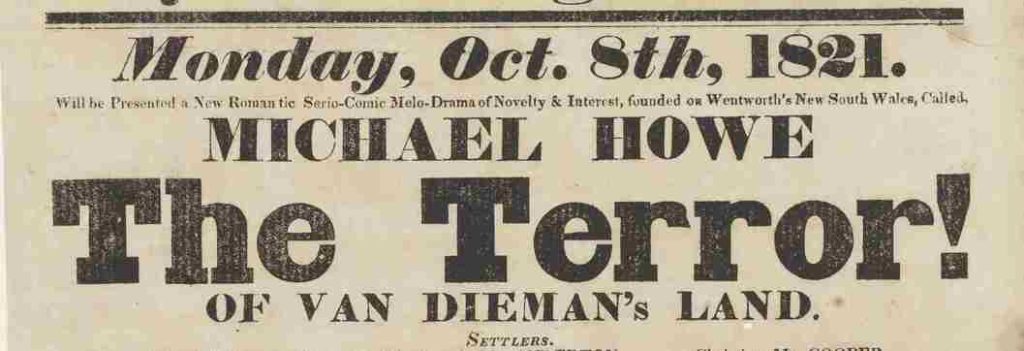

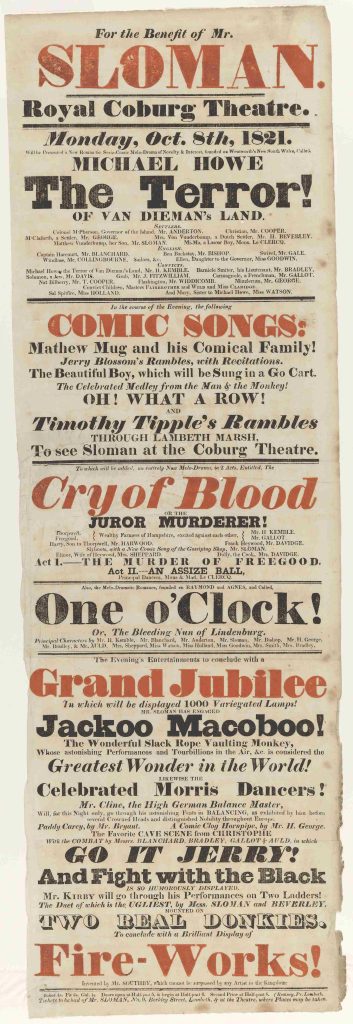

Barely three years after his death, Howe’s exploits formed the basis of a melodrama by the prolific, popular and now-forgotten Anglo-American dramatist John H. Amherst (1776?-1851). Michael Howe the terror! of Van Diemen’s Land premiered at London’s Royal Coburg Theatre in April 1821. It is noted as the first play to be produced about Tasmania. Although panned by the critics, it must have been commercially successful. It was revived in October 1821 as a benefit for the actor Henry Sloman (1793-1873). The Royal Coburg was one of London’s leading theatres. Opened in 1818, it became the Royal Victoria Theatre in 1834. By the 1880s it was known as the Old Vic.

Only a handful of Amherst’s plays were ever published. ‘Michael Howe’ was not one of them; no surviving manuscript is known. The State Library of New South Wales has a poster for the April production, the Allport Library and Museum of Fine Arts has one for the October revival. Both these posters are unique survivors. When they are read carefully, they yield substantial information about the play. The names of the characters, and the exclamation mark after ‘Terror!’, indicate that it was typical of Amherst’s melodramatic style. The October poster identifies the source of the play: not The last and worst of the bushrangers, but W C Wentworth’s Statistical, historical, and political description of the colony of New South Wales (London, 1820), which drew on reports published in the Sydney Gazette.

The posters also give a vivid picture of a night out at the theatre in Regency London. And what a night it was. Most of the crowd were probably more-or-less sober for the first show, Michael Howe. After that, a light-hearted song and dance act, colour and movement: time to head for the bar. Then another over-the-top melodrama designed for booing and cheering, followed by another even gorier (the title One O’Clock may indicate its starting time). Towards sunrise, the stage was graced with ‘Jackoo Macoboo the wonderful slack rope vaulting monkey’, Morris dancers, a boxing match, donkeys, and fireworks. By then, it is safe to assume, the audience was making its own fun.

Armed with all that information, it must be possible to devise a plausible reconstruction. Okay, maybe not the donkeys and the fireworks. But the first play about Tasmania! Go to it.

Shadows alive

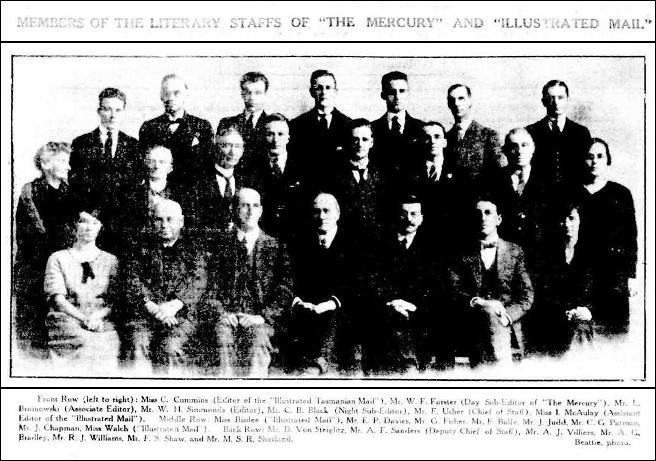

The ABC Library recently transferred to Libraries Tasmania the only known copy of Shadows alive, a radio play about Martin Cash written by Hobart journalist Frederick Stanley Shaw. Little was known about Shaw. According to Austlit, he was a journalist at the Hobart Mercury, and author of The victory of life and other poems (London, 1931). Libraries Tasmania’s copy of The victory of life is inscribed to Fred Usher, editor of the Illustrated Tasmanian Mail.

Trove newspaper searches revealed that ‘Shadows alive’ was broadcast in Hobart in August 1933 (Mercury 28 August 1933, p.4), and nationally in June 1935. Frederick Shaw and his wife Hilda appeared frequently in the social pages from the early 1920s to the late 1940s, hosting social events at their home in the affluent suburb of Sandy Bay. Frederick joined the ‘literary department’ of the Mercury around 1924 (Mercury 5 July 1924, p.20), and was a regular public speaker on historical subjects including the history of the press in Tasmania. In 1925 an F S Shaw formed a company with Professor T T Flynn (father of Errol) to revive the fish cannery at St Helens (Mercury 19 November 1924, p.4; Daily Telegraph (Launceston) 15 September 1925, p.4).

At a 1946 ABC-sponsored public debate on military training in peacetime, held at the State Library, Frederick Shaw was one of the proponents of the ‘yes’ case (Mercury 12 Dec 1946, p.18).

After Hilda’s death in 1951, Frederick abruptly disappeared from view. She was buried at Cornelian Bay, he was not.

So where did he come from, and where did he go? Twentieth-century records are difficult and frustrating to search, but Trove newspapers gave enough clues to enable fruitful searches of family history resources Ancestry and Find My Past (both of which you can access for free at the library). Gradually, as false leads were eliminated, a picture emerged.

Frederick Stanley Shaw was born in 1878 in Alton, Staffordshire, the fifth child of school teachers Edward and Benedicta Shaw. In 1888 Edward and Benedicta were appointed Superintendent and Matron at Bradwall Reformatory School, Cheshire, and remained there until their retirement in 1913. Frederick followed his parents’ career and became a school teacher in Liverpool. He married Hilda Moore-Williams in 1909. Their son Wellesley Raymond Moore Shaw was born in 1913. In December 1917 Frederick was initiated into the Abercromby Lodge of the United Grand Lodge of England. By then he was a Lieutenant in the King’s Liverpool Regiment, and had seen active service in France.

In 1920, with several of Hilda’s relatives, the Shaws emigrated to Tasmania. Before turning to journalism, Frederick managed an orchard at Glenorchy, near Martin Cash’s property, with Hilda’s brother Graham (Mercury 20 April 1921, p.8). Shadows alive was presumably conceived, if not written, at the orchard.

After Hilda’s death, Frederick moved to New Zealand to be with their son. Wellesley had emigrated to Dunedin in the 1930s, married there, and served in the New Zealand Army (supplement to the London Gazette, 13 October 1942). Frederick Stanley Shaw died in Wellington on 29 June 1964.

Further reading

James Boyce, Van Diemen’s Land (Melbourne: Black Inc, 2008)

After Hilda’s death, Frederick moved to New Zealand to be with their son. Wellesley had emigrated to Dunedin