Tasmania Reads: Reading an Account of the Voyage of a Convict Transport (Part Two: The Answer and Historical Background)

The State Library and Archive Service is issuing a challenge to Tasmanians to read five different examples of nineteenth-century handwriting from our Heritage Collections, each featuring a different set of records held in the State Archives.

Just to recap:

Your Transcription Challenge

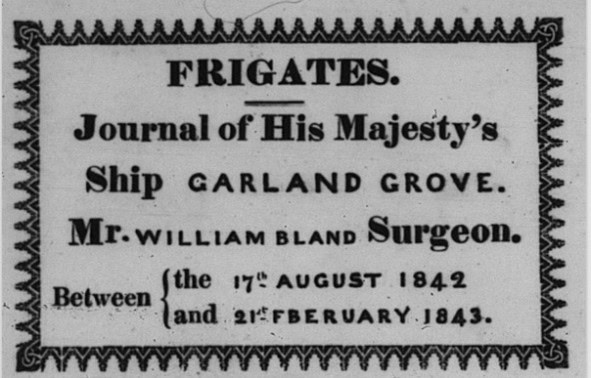

Your first challenge is to transcribe a passage from the account of the voyage of the Female Transport, Garland Grove (2) in 1842/1843:

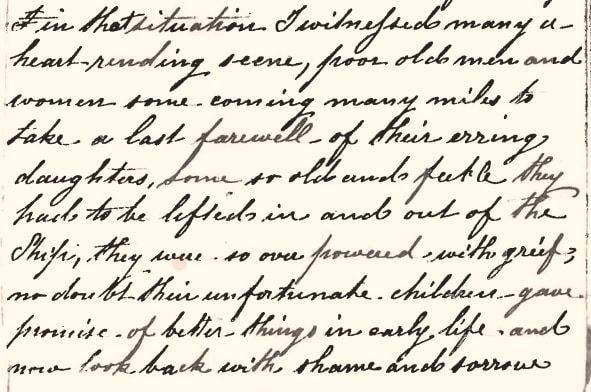

The Answer

…in that situation I witnessed many a heart-rending scene, poor old men and women some coming many miles to take a last farewell of their erring daughters, some so old and feeble they had to be lifted in and out of the Ship, they were so overpowered with grief, no doubt their unfortunate children – gave promise – of better things in early life, and now look back with shame and sorrow …

Historical Background: The ‘Erring daughters’

The “erring daughters” referred to by Abraham Harvey were among the 1350 female convicts transported to Van Diemen’s Land between 1803 and 1853. The number of men transported for the same period was five to six times that amount. These women were in high demand, as marriage partners for the younger transportees, and as domestic servants for the older or less genetically blessed. Marriage, the authorities believed, encouraged stability, and had the added benefit of any children resulting from the union being future labourers and servants for the Colony.

Without women, the men of the Colony were in danger of partaking of “the dreadful crime … the importation of these young women meant the vengeance of Heaven [could be] averted.” (The Cornwall Chronicle, 28 Nov 1846, p.917)

Because of the gender imbalance in the Colony a young female convict had options. She could marry a convict still under sentence, a convict whose sentence had expired, a free born son of an ex-convict, or a free settler.

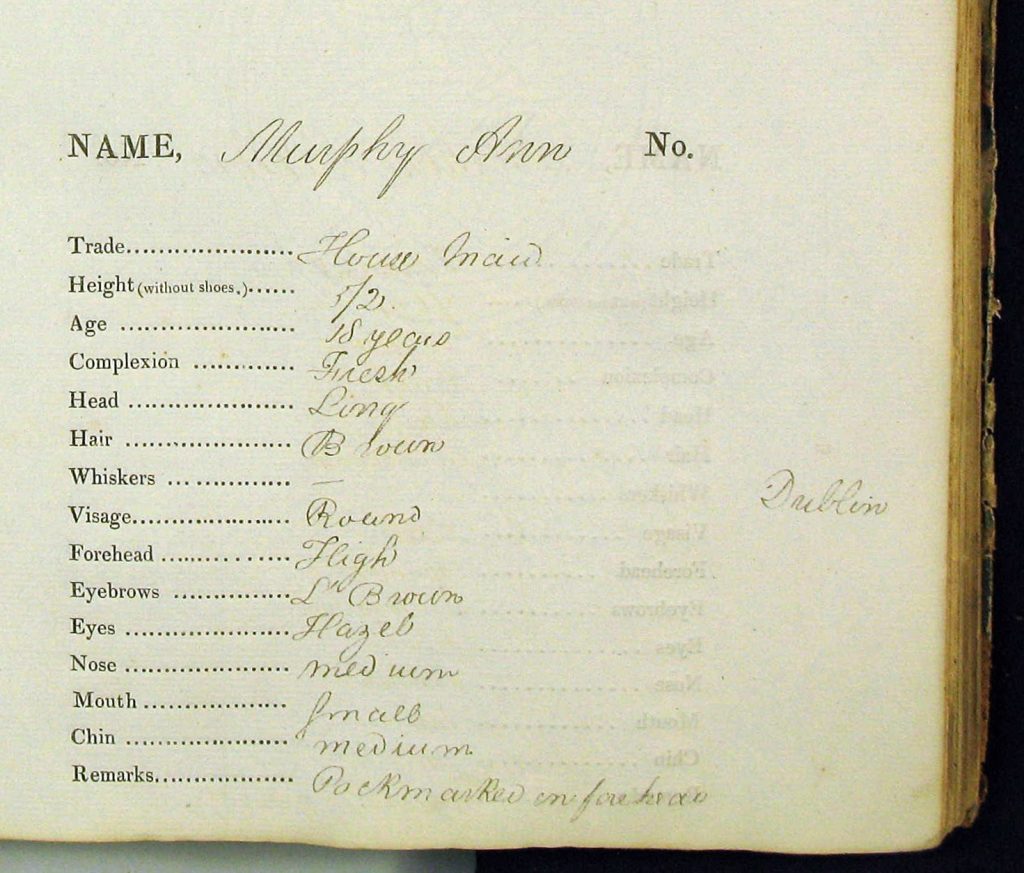

Marrying a free settler was the best option. For example, this was achieved by Ann Murphy a convict nursemaid who arrived in 1840 aged 16.

A few years later in July 1844 she married Roger Pitt a free 21-year-old Coachmaker.

Marrying a free man who had not been a convict and had a valuable trade was a step up for a convict woman.

But it was more likely that a woman would marry a man still under sentence or one who was emancipated, or a free born child with convict parents. The man’s necessary qualifications were an ability to earn sufficient income to provide a home for a wife and any future children and to be able to demonstrate this to the Governor’s satisfaction.

The approval of the Governor was required before convicts could marry, with marriage regarded as an indulgence to be granted at the Governor’s discretion. The indulgence came via the Principal Superintendent and required character references attesting to the convict applicant being deserving and eligible.

Convicts soon realised if they wanted to be granted the privilege of marriage, they needed to have a good conduct record. It was not unusual for first applications to be denied and the applicants told to reapply after a period of consistent good behaviour.

Some of the early applications to marry include wonderfully informative letters from family back in England. These were kept with the Colonial Secretary’s records as news in the letters included statements about the death of a spouse, providing the proof that the recipient of the letter was free to marry.

The number of convict arrivals of both sexes peaked in the early 1840s, a period known as the Hungry Forties, when the Garland Grove (2) arrived. Many young people had been forced to leave their families in rural England and Ireland for the overcrowded cities in search of work. Low wages and lack of employment tempted many into crime. Opportunistic theft of items from their employers accounted for many transportees with 91% of convicts transported for petty theft. While many women were described as “on the town” (a euphemism for prostitution), it was for most a necessary part-time occupation to supplement a meagre income.

Years of deprivation on the streets and in workhouses resulted in poor health for many of the convict women who were leaving on the Garland Grove (2).

The “poor old men and women” who came to wave their loved ones goodbye had cause for concern. Those being transported were checked and deemed healthy enough to survive the voyage, but the reality was some came on board in such a debilitated state of health that they were not fit to sail and did not survive the voyage.

The long sea voyage was especially hard on frail mothers nursing children. Abraham Harvey counted 25 children on board with their mothers. The official records don’t mention them, except when they died, and then not by name.

It was the 2nd of October 1842 when the Garland Grove (2) left Woolwich carrying its cargo of female convicts and their children. The voyage was to take 109 days, with a total of 179 women and some children arriving at Hobart Town. The voyage from Woolwich to Hobart must have been hellish for these women.

A typed transcript of the Abraham Harvey’s account of the entire voyage has been made available online by the Female Convicts Research Centre. The Surgeon Superintendent on the voyage was Robert William Bland whose task was to look after the health of the women and children on board and to write a full report on any illnesses.

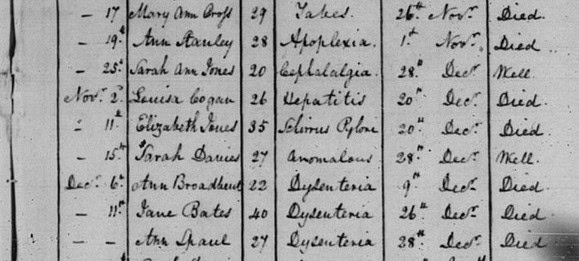

Unfortunately, within days of the ship leaving port women started to fall sick. For many it was sea sickness and they recovered, but others did not. Eight women died on this voyage making this the second equal highest number of fatalities on a female convict transport, barring shipwrecks. The highest number of fatalities was yet to come with seventeen on the East London in 1843, but the average number for the women over the entire period was two or less. In this regard the female transports fared slightly better than the men, but generally only a couple of deaths occurred on the voyage for either sex.

Of the eight women who died five were still feeding their infants when they came on board. One mother died shortly after giving birth and her baby followed her after a few days. As the mothers got sick and lost their milk other women, nursing mothers themselves, attempted to feed the babies of the sick. However, all the babies whose mothers died, also died making the real number of fatalities thirteen.

Surgeon Superintendent Bland wrote in his report, “it is almost impossible to keep one of this age [an infant] alive without milk and a good nurse when at sea in a ship.” No nursing mother would give her milk to another baby at the expense of her own infant.

Bland is not sympathetic in his accounts of the some of the sick women, describing them as filthy and indolent, and having led desolate lives. Of Louisa Cogan he remarked she had a “peevish and troublesome temper” and suffered from “violent hysteria.” She was 26 when she died. The cause of death was “hepatitis”. He treated her “hysteria” by cutting her hair off and applying cold compresses regularly to her head. Misbehaviour was not to be tolerated even in the dying.

Ann Stanley had attempted suicide in prison, and “would not feed her [newborn] child.” Her head was shaved, and cold lotions applied constantly. She was 28 when she died of “apoplexia” [a stroke] following childbirth and her baby died a few days later. She had been complaining constantly of headaches. Surgeon Superintendent Bland writes contemptuously, “this woman for want of a stimulant drank vinegar pure.”

Second Officer Abraham Harvey’s account of Ann Stanley’s funeral shows he stills experienced some sympathy for the fate of the women although he doesn’t seem to know Ann’s name and corrects himself from calling her one of the ..convict women presumably.. to “a poor woman.” He writes:

![Second Officer Abraham Harvey’s account of Ann Stanley’s funeral. it reads: “Hereabouts occurred our first funeral, it was that of [“one of the” crossed out] a poor woman, who died the night before 6 o’clock in the evening the Ship was hove too, the body brought to the gangway placed on a grating in presence of most of the women, and the Ship’s Crew – covered with the Union Jack, for a pall it was a solemn and affecting sight the burial service was read by the Commander and I officiated as Clerk, when we came to ‘We therefore commit her body to the deep, to be turned into corruption, looking for the resurrection of the body, when the Son shall give up her dead, and the life of the world to come through our Lord Jesus Christ’, the body was launched into the deep, a universal shudder came over all present.”](https://cdn.shortpixel.ai/spai/q_glossy+to_auto+ret_img/libraries.tas.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/NS816-1-1-p10.jpg)

“Hereabouts occurred our first funeral, it was that of [“one of the” crossed out] a poor woman, who died the night before 6 o’clock in the evening the Ship was hove too, the body brought to the gangway placed on a grating in presence of most of the women, and the Ship’s Crew – covered with the Union Jack, for a pall it was a solemn and affecting sight the burial service was read by the Commander and I officiated as Clerk, when we came to ‘We therefore commit her body to the deep, to be turned into corruption, looking for the resurrection of the body, when the Son shall give up her dead, and the life of the world to come through our Lord Jesus Christ’, the body was launched into the deep, a universal shudder came over all present.”

Surgeon Superintendent Bland’s physical description of Ann as “a short fat figure with a very thick neck and small skull, and she is mentally weak,” suggests that she may have had Downs Syndrome. But no allowances were made for this in her treatment.

More deaths were to follow: on the 26th of November, on the 9th of December, two on the 20th of December, one on Boxing Day, and the last on the 28th of December 1842.

Harvey does not mention the convict cargo again in his journal, except on the 9th of December: “shipping much water on M [Main] deck. The women had to go on to the poop and that would have given you a good idea of a slave ship of the old time. The difference being ours were huddled together on deck and theirs in the hold.”

This was the day that Ann Broadbent aged 22 died of dysenteria (sic). Her death is not recorded by Harvey.

The Garland Grove anchored at Hobart Town at 9pm on the 20th January, ending what must have been a nightmarish journey, with four women dying within an eight day period over Christmas.

However, the suffering wasn’t over for them yet. Many of the 179 women who landed at Hobart still had their children. Those with babies were able to keep them at the Female Factory until they were two years old and then, unless they could get a placement where they could take their child, the toddlers were placed in the orphanage.

Children off the ship over two years old were admitted to the Queens Orphan School within a few days of landing. It is notable that most of the women who had children with them were very well behaved on the voyage out. One exception to this was Margaret Bouchier, who had another child within two years of arriving.

These are the names of some of those children and their mothers report cards from the Surgeon Superintendent:

Ester Howell aged 8, the daughter of Esther Howell. Surgeon’s report: very good and industrious

William Bouchier aged 4, the son of Margaret Bouchier. Surgeon’s report: bad temper

James Moore aged 8, the son of Ann Williams.

Louisa Moore aged 8, (twins?) the daughter of Ann Williams. Surgeon’s report: assisted in the hospital

William Hunt aged 10, the son of Sarah Ann Hunt. Surgeon’s report: very kind to the sick

James Parker aged 5, the son of Jane Parker. Surgeon’s report: very good

Mary Ann Tapp aged 14, the daughter of Ann Tapp. Surgeon’s report: good.

Elizabeth Tapp aged 7, the daughter of Ann Tapp

Ann Tapp had either two or three children, and was either married or single (both are written on her conduct record- but this could mean she was in a de facto relationship and perhaps only two of her three children came with her). She was convicted of stealing mutton. Her gaol report was “Bad”, and presumably she had her children with her in the gaol. Her conduct on board the Garland Grove was good. When she arrived, she stated she was 45 years old.

A year after she arrived, she applied to marry Samuel Haynes who was free. Then her stated age was 34 and she said she was a widow. The marriage took place in May 1844, and in October 1844 the Haynes welcomed a baby boy, Samuel. Ann has no transgressions recorded on her conduct record, nor do we know where she was living when she met Samuel. As the marriage took place in New Town, it is most likely that they were both living there. The Orphan School was also located in New Town.

In February 1844, fifteen-year-old Mary Ann Tapp was apprenticed from the orphanage to G.F. Read Esquire of New Town and on the 6th October 1844 Elizabeth Tapp, now 8 years old was discharged to the care of her mother.

At least for the Tapp family this sad voyage had a happy conclusion.

Bibliography

We have too many resources to list them all here so please follow these links for further reading:

All Resources

Women Convicts (Tasmania) and Convict Ships

Online (including eBooks)

Women Convicts (Tasmania) (online only) and Convict Ships (online only)