Sewing for freedom: clothes production at the Cascades Female Factory

This blog is one of a series that explores in greater depth some of the fascinating stories that we uncovered while researching Duck Trousers, Straw Bonnets, and Bluey: Stories of fabrics and clothing in Tasmania, an exhibition currently on display in the State Library of Tasmania and Tasmanian Archives Reading Room in Hobart. These blogs are designed to complement the exhibition, expanding some elements of the exhibition story walls to provide more context and different perspectives.

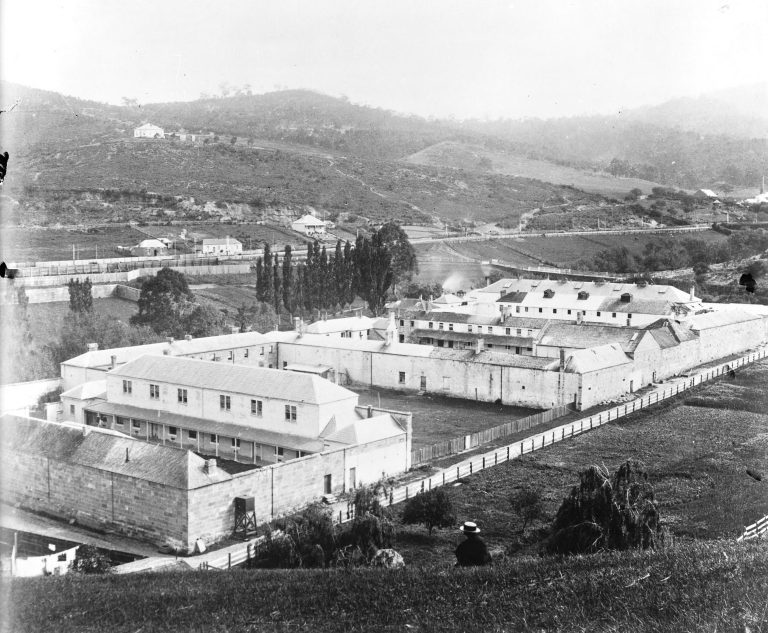

Female Factories in colonial Van Diemen’s Land were arrival and hiring depots, as well as somewhere to house those who were unfit for service outside, whether ill, rebellious, or pregnant with nowhere else to go. They were also the instrument of systematic and severe punishment of convict women for often minor offences and were also known as a ‘Female House of Correction’. Thanks to the Convict Department’s aims of strict discipline, control and reform through hard labour, which it was hoped would earn enough money to help to cover costs, women worked long hours at tasks including standing for hours in the cold at outdoor laundry tubs, picking apart old tar-laden ropes, spinning wool, and sewing and clothes-making.

When penal policy was revised in the early 1840s and the Probation system took effect, the focus shifted to reforming and preparing inmates for freedom, keeping them hard at work to learn useful life skills. However, harsh, overcrowded and often chaotic conditions in the Female Factories throughout the convict period meant that only unskilled tasks such as laundry work were a constant. It was not until the final years of transportation that there was a steady flow of clothes production in any of the Factories. At the largest establishment, Cascades Female Factory, this was most successful during the regime of one zealous administrator.

Charting Success

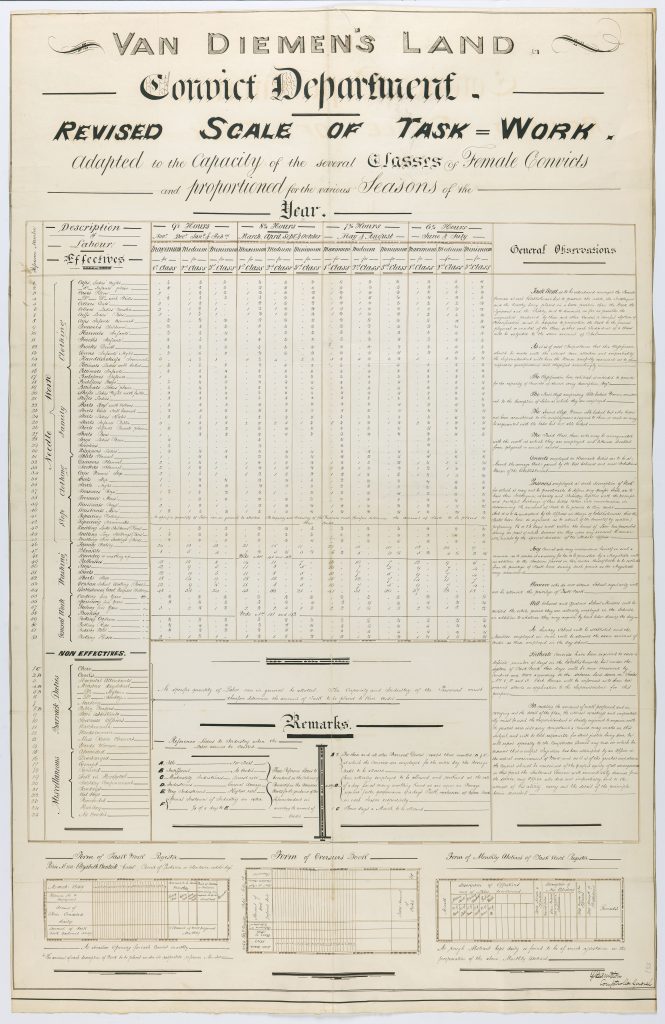

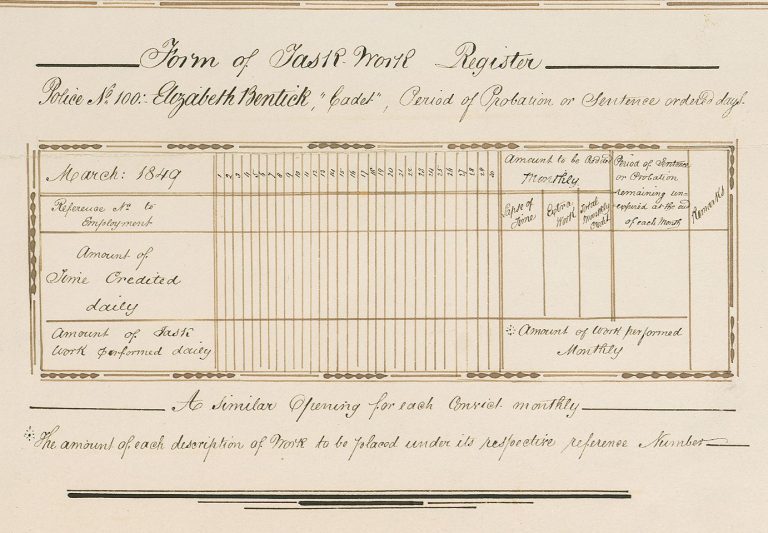

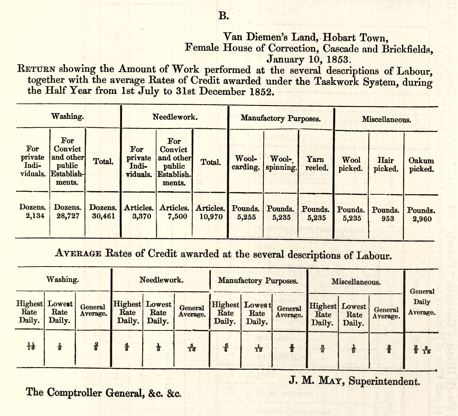

In his office above the forbidding entrance to Hobart’s Cascade Female Factory in early 1852, Superintendent J. M. May added a handsome new item to his tools of trade – a large, meticulously detailed wall chart entitled, in highly decorative scripts, “Van Diemen’s Land Convict Department Revised Scale of Task Work Adapted to the Capacity of the several Classes of Female Convicts and proportioned to the various Seasons of the Year” (Tasmanian Archives: GO33-1-100) Signed by the Comptroller-General of Convicts, J.S. Hampton, the content of the new chart was a revision of the scale of task work of 1849, when a more formalised system of labour was introduced in those female factories still operating — Cascades, Launceston and Ross. In this new system, each convict had a daily work target with credits allotted. If she exceeded her target, extra credits earned her a faster road to freedom.

The 1845 Probation system regulations for female convicts had included around 20 different garments that could be sewn or knitted and purchased by the general public (Regulations of the Probationary Establishment for Female Convicts in Van Diemen’s Land, 1845, Tasmanian Archives: GO33-1-52, p763-784) but the task work scales of 1849 and 1852 more than doubled that number and added such ‘fine needlework’ items as “shirts gents’ full bosomed” and “shifts ladies’ night with frills”. The long hours of work prescribed on the scale were adjusted to each season, and each garment or other type of task earned a fixed amount of credit for each class of convict. Any inmate who chose to “misconduct herself” might be excluded from “the privilege of Task Work during such period as the Magistrate may recommend.”

The Revised Scale of Task Work appeared to be scrupulously fair in allowing those allocated to general tasks in running the Female Factory to also earn credits, and ensuring that:

“The ‘active, the intelligent and the healthy’ were not placed in a better position to gain Task Work credits than ‘the weak, the ignorant and the sickly and to diminish as far as possible the inequalities produced by these and other causes’ “

A detailed monthly credit register was recorded for each convict according to this model:

An Appetite for Severity

However fair the task work system may have been, Superintendent May’s strong feelings on penal reform closely reflected those of British reformers of the time: “encouragement to good behaviour by enforcing silence and self-control”, constant surveillance and the strictest discipline. His severity in enforcing these principles was “possibly even more than British reformers would have approved”.

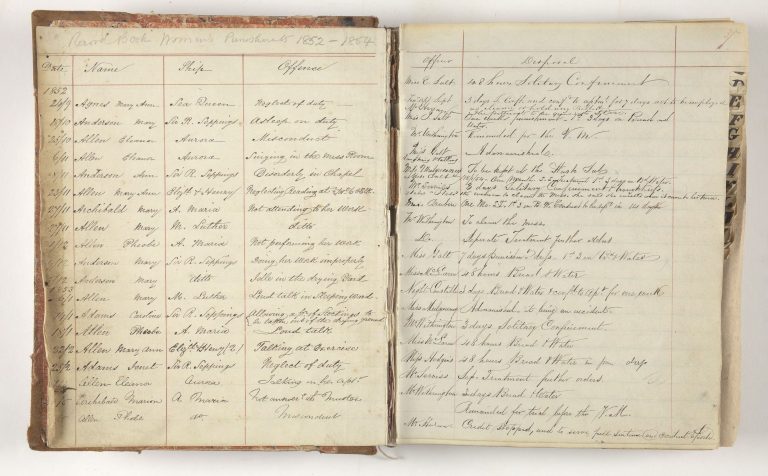

Life at the Cascades Factory had always been hard, with harsh regulations, constant overcrowding, insufficient food and the relentless cold and damp environment of a high-walled compound in a sun-starved valley. Now, talking amongst inmates in virtually any circumstances – at the mess table, at muster, at work, in the dormitories – was a punishable offence. It’s endearing to see that high-spirited behaviour such as ‘singing and dancing’ and ‘making signs and laughing in Chapel’ persisted, despite the looming risks. Other offences included untidiness, neglect of work and the absurdly minor act of “sleeping in her cap” (Alexander, ed. Repression, reform & resilience, 2016, p. 156-160). At the Sunday muster of all inmates, the names, offences and sentences of the latest offenders were read out as an additional humiliation.

Punishments included demotion to the laundry tubs, a spell on bread and water, days or weeks in the total darkness of a solitary cell (with reduced rations) or locked in a very small, isolated ‘separate apartment’ or ‘light working cell’, with just enough light to work by (even sewing was expected). May proudly reported in 1853 that during the past 6 months: “the whole of the separate apartments have been constantly in use”, providing “favourable opportunity for inculcating new principles in the mind” (Correspondence and returns relating to convicts in Van Diemen’s Land and to convict discipline and transportation, 1851/54, 1969, p. 341). And of course, the “privilege” of task work might be withheld.

Impressive Outputs

May stated in his extensive 6-monthly Superintendent’s report of January 1853 that the Cascades Factory and the Brickfields Hiring Depot had been extremely productive in garment making: 10,970 articles of needlework. Apparently “demand for every description of work for private individuals, arising from the general scarcity of labour” had increased to the point that “large quantities of every description of work (had) been refused” so that they could keep up with demand for washing and needlework from several public establishments. May stated that he could not ‘overrate the beneficial influence… produced on the minds and habits of the women” by the task work system.

In his report May included no less than 29 glowing compliments from the “Strangers Visiting Book”, including: “…from the system and cleanliness, (we) consider great credit is due to the Superintendent” and “I have visited, I may say, every penal establishment in the island, and have never found any so efficiently conducted” (Correspondence and returns relating to convicts in Van Diemen’s Land and to convict discipline and transportation, 1851/54, 1969).

It seems May was also riding a wave of success begun by his predecessors at the Cascades Factory, as two months before he began the role of Superintendent, a visitor to the Factory had reported: “We next had a glimpse of a room full of sempstresses, most of them employed on fine work.” (Mundy, Our antipodes, 2006 (abridgement of three-volume 1852 edition), p. 219).

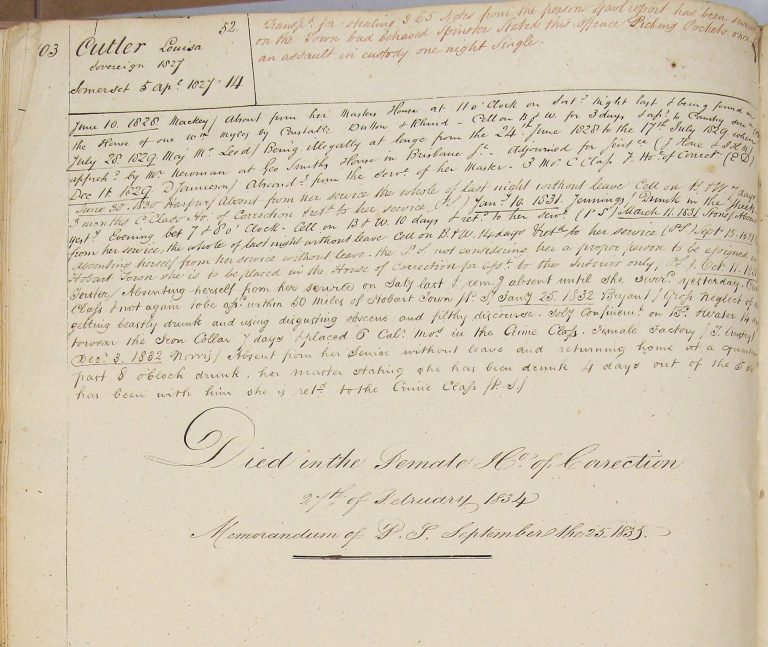

Extra staff including a needlework teacher had been appointed to the Factory in mid-1851 (Rayner, The female factory at Cascades, Hobart, p. 38), which no doubt helped support the impressive output of 1852, for those female convicts who already had needlework skills were not always able to contribute them. Take the tragic case of Louisa Cutler, a dressmaker and needle-woman sentenced to transportation for picking pockets: her Conduct Record shows a sad tale of absconding from assignments, extreme drunkenness, sentence after sentence to harsh punishments, and finally an early death at the Factory (Alexander, ed. Repression, reform & resilience, 2016, p. 41). You can view Louisa’s convict records in the Tasmanian Names Index.

Freedom by Default

Only three months after May’s impressive report, the last ship carrying convict women arrived in Hobart, and convict transportation to Van Diemen’s Land ended (Rayner, Female factory female convicts, p. 173). From a slow grind towards freedom via task work credits, inmates of the female factories were suddenly fast-tracked through their sentences by an administration that had lost interest in how to manage or even think about convict women. The focus was to “get the final pass-holders through the system and off the account books as quickly as possible” (Frost, Footsteps and voices, p. 44). Numbers dropped dramatically at the three remaining female factories and in 1856 part of the Cascades Factory complex was declared a gaol. By early 1857 there were less than 900 female convicts still under sentence left in the entire colony (Rayner, The female factory at Cascades, Hobart, p. 38).

Systematic clothing production at the Factory may have come to an abrupt close, but if some of the women who’d toiled away took with them a new set of needlework skills, then the convict Probation system had, in some measure, done its job.

Out with Mr May

In 1856, the energetic Mr May’s career took a downward turn when a government enquiry found that despite the much-promoted productivity, cleanliness and efficiency of the Cascades Factory under his regime, “recklessness and mismanagement” by himself and Comptroller-General Hampton in allowing constant exposure to cold, and insufficient clothing and food, had led to “excessive mortality” of infants in the nursery (Courier, 7th Feb. 1856, p.2). (May had casually referred in his 1853 report to the deaths of 57 children in the second half of 1852 as a “trifling increase” over deaths in the previous year.)

May and other officials were also found to have exploited convict labour and misappropriated Government owned stone, bricks and timber for their own use. May was dismissed (Alexander, ed. Repression, reform & resilience, 2016, p. 264) and Hampton “made an ignominious escape from the colony” rather than face the charges (Cornwall Chronicle, 22nd Sept 1858, p. 4).

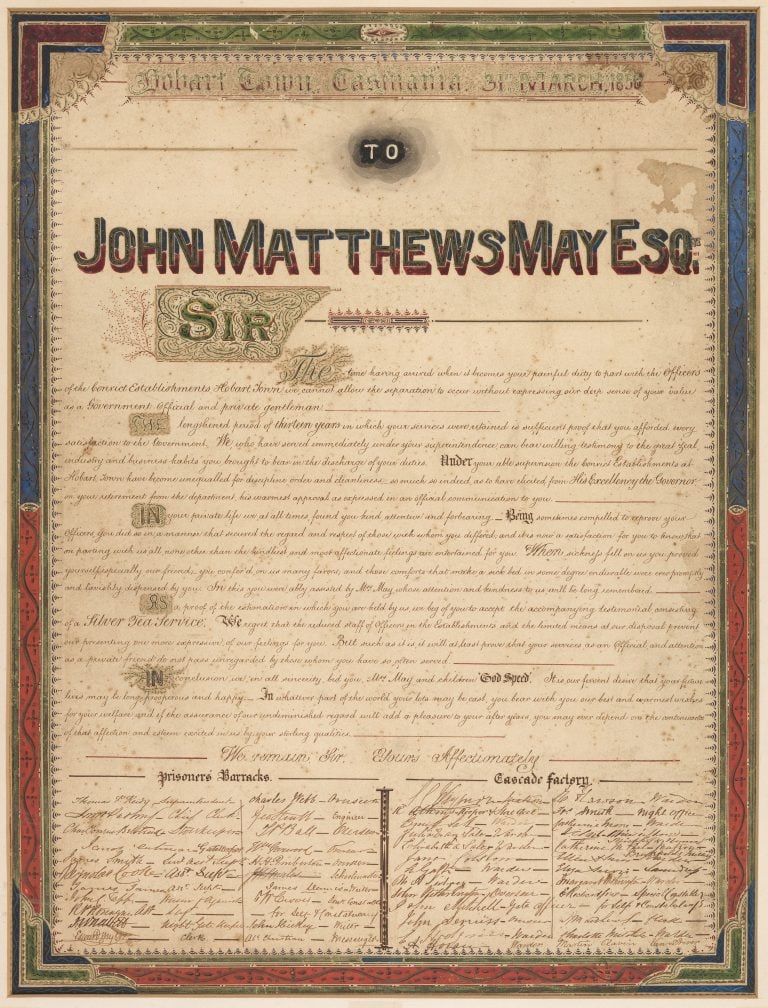

Despite his disgrace, in March 1856 May was presented with an elaborate and highly complimentary farewell “Illuminated Address”, signed by staff of both the Cascade Factory and the male Prisoners’ Barracks (which had been added to May’s duties in 1854):

Given May’s talent for self-promotion, some were clearly suspicious that this document was:

Tasmanian Daily News, April 28, 1856, p. 2

References

State Library of Tasmania

Alexander, A., ed. Repression, reform & resilience : a history of the Cascades Female Factory, 2016

Frost, L. Footsteps and voices : a historical look into the Cascades Female Factory, c2004

Mundy, G.C. Our antipodes, 2006

Rayner, T. Female factory female convicts : the story of the more than 13,000 women exiled from Britain to Van Diemen’s Land, c2004

Rayner, T. The female factory at Cascades, Hobart, 1981

Correspondence and returns relating to convicts in Van Diemen’s Land and to convict discipline and transportation, 1851/54 Shannon: Irish University Press in co-operation with Southampton University, 1969

Tasmanian Archives

Tasmanian Archives: Plan/Map – Oversize Chart of Convict Department Revised Scale of Task Work Adapted to the Capacity of the several Classes of Female Convicts and proportioned to the various Seasons of the Year, GO33/1/100

Tasmanian Archives: Photograph – Female Factory, Cascades from the East, NS1013/1/48

Tasmanian Archives: Register of offences and punishment ordered at the Hobart Female House of Correction, CON138/2/1, Index A- Page 37 (1852) in Duplicate Dispatches, GO33/1/52, p763-784 (Regulations of the Probationary Establishment for Female Convicts in Van Diemen’s Land, 1845)

Tasmanian Archives: Illuminated Address to John Matthews May Esq. on his departure as Superintendent from the Convict Establishment, Hobart Town, signed by the staff of the Prisoners Barracks and the Cascade Factory, NS402/1/1

Newspapers

Courier, 7th February, 1856

Tasmanian Daily News, 28th April, 1856

Cornwall Chronicle, 22nd September 1858

Online resources

Convict Institutions (femaleconvicts.org.au)

Van Diemen’s Land, Convict Department, Revised scale of task work adapted to the capacity of the several classes of female convicts & proportioned for the various seasons of the year (1849) https://www.femaleconvicts.org.au/convict-institutions/task-work