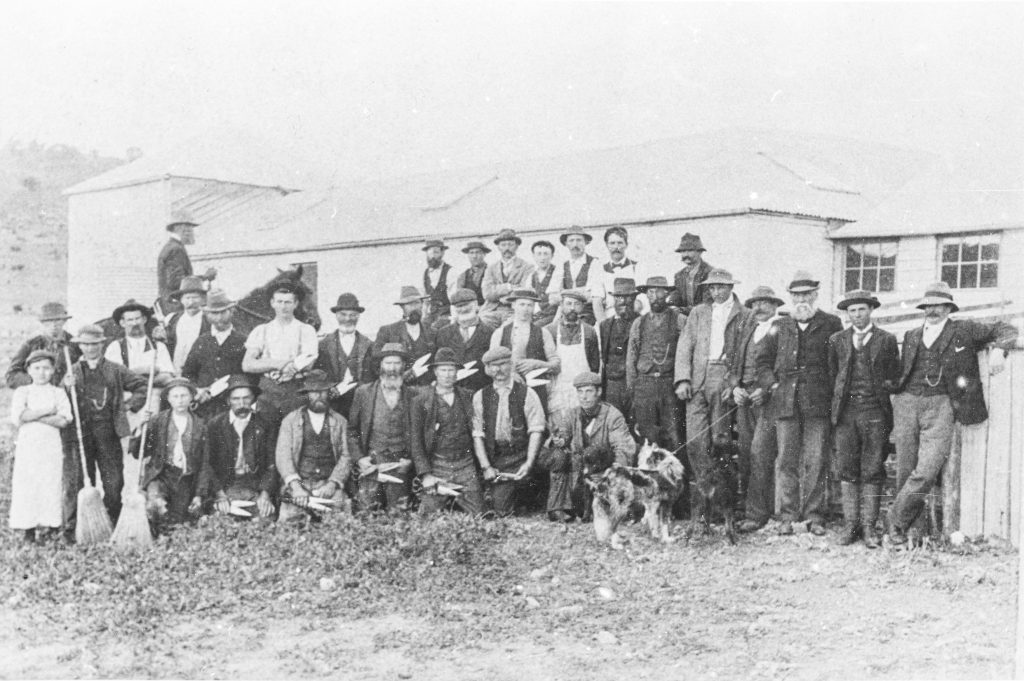

Reading, Writing & Arithmetic: The Public School Curriculum 150 Years Ago

What would you have learned at a Tasmanian public school in 1869? Mostly, just reading, writing and arithmetic, from a teacher not much older than yourself, in a class of 40-60 students, and in a textbook that your grandfather might have read in Ireland thirty years earlier. The texts might have been boring and out of date, but the reasons why are fascinating. That’s because the public school curriculum in 1869 was deliberately designed to be bland and uninteresting, in order to avoid social conflict. What follows is the story of a journey – from the idea that education needed to reform and contain children, to the radical idea that children in public schools should be inspired to learn, and to become curious and informed citizens. Read on to discover more!

For an audio introduction to this story, check out our interview with ABC Radio!

Transcript of the interview

00:00:00 Speaker 1

ABC Radio Hobart and across Tasmania as your afternoon. If you were in a classroom in this state in the late 1800s. You probably would have studied from an Irish textbook.

00:00:13 Speaker 1

You also might have picked up a brutal chest infection from the coal fire, but that’s another matter. It’s not quite a tablet device for every student, is it?

00:00:22 Speaker 1

This year marks 150 years of public education in Tasmania and the Department of Education has a series of events to commemorate that, like a travelling exhibition, visiting libraries around the state, to talk about the history of education and the ABC’s Georgie Burgess has sat down with archivist Anna Clayton to go through some textbooks. Which were used in Tasmanian schools from when education became compulsory in 1868, and she found out why exactly they were Irish ones.

00:00:53 Speaker 2

The greatest part of the settlers are men who were wicked in their own country and become still more so here from the influence of bad examples amongst them. Hi, I’m Anna Clayton, and I’m an archivist at the state library and archive service here in Hobart.

00:01:07 Speaker 3

Anna, you and I whispering to each other at the moment. Why is that?

00:01:12 Speaker 2

That is because we are in the history room at the state library, and we’ve got a couple of researchers doing research at the far end of this wood panelled room with all of our beautiful books and priceless paintings in it, so we’re trying not to bother them too much.

00:01:30 Speaker 3

So we’re having a bit of a chat about what was on the curriculum in Tasmania 150 years ago and what do we have in front of us at the moment.

00:01:41 Speaker 2

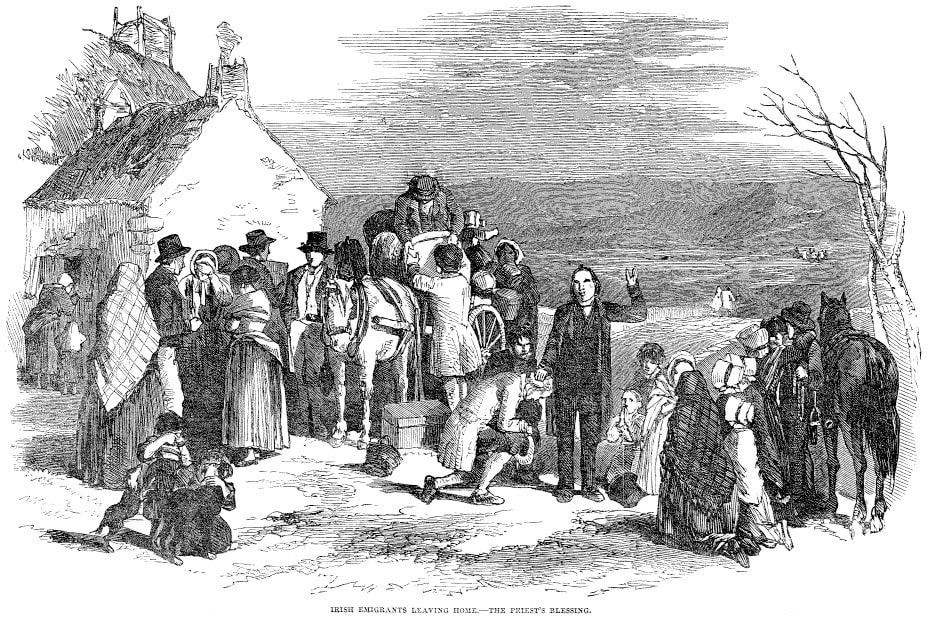

Well, we have a variety of textbooks in front of us that would have been used in Tasmanian public schools, including those that would have been used when public schooling became compulsory in 1868 and those are called Irish national readers. And if you are at all curious about why Tasmanian public schools are using Irish national readers, the first reason is because they were cheap and they were plentiful and they were very widely circulated throughout the British Empire, and most of the English speaking colonies. And the reason for that is that they’re designed to be non sectarian. And to understand why that’s important, we had to kind of walk back a little bit and to not think about Tasmanian public schools in 1860 but think about Ireland in 1831 because the fact of the matter is that lots of school children, all public school children in Tasmania who were of Irish descent in 1868, would have been reading textbooks that their grandfathers and grandmothers would have been reading in Ireland 40 years earlier, possibly before they were transported for theft, for maybe stealing a loaf of bread during the height of the potato famine.

00:02:57 Speaker 2

And the reason for that is that the British government instituted a programme of national education in Ireland in the 1830s to try to solve some of the bitter sectarian conflicts that were roiling the island. They saw public schooling as a way to institute a kind of morality, the object wasn’t to make children curious. It wasn’t to make them excited about learning. It was to teach them morality, and the only way that they could think of to do that was to appeal to Christianity, to teach fundamental moral concepts. But of course the problem was that the majority of the Irish population were Catholic, and the British ruling class were Protestant. And to avoid conflict they tried to make these textbooks as bland and as unobjectionable as possible to make them non sectarian and then what happens is that as a result of conditions in Ireland and particularly as a result of the potato famine, you have this mass diaspora of Irish people around the British Empire and you then end up with populations of Catholics and Protestants living together.

00:04:14 Speaker 2

Outside of Ireland and Canada in Australia and in New Zealand, a lot of those tensions between Catholic and Protestant populations get transported with them.

00:04:24 Speaker 2

So the end result is that in Australia and in Canada and in New Zealand, You see people using these Irish national readers in an attempt to instil drive morality into the skulls of the youth, and to do so while avoiding social conflict.

00:04:44 Speaker 3

And this would have been all throughout the colonies in Tasmania that they were being taught this?

00:04:49 Speaker 2

Yeah. So the Irish national readers are the textbook of choice for all public schools in in Tasmania. And there actually a couple more reasons for that.

00:04:59 Speaker 2

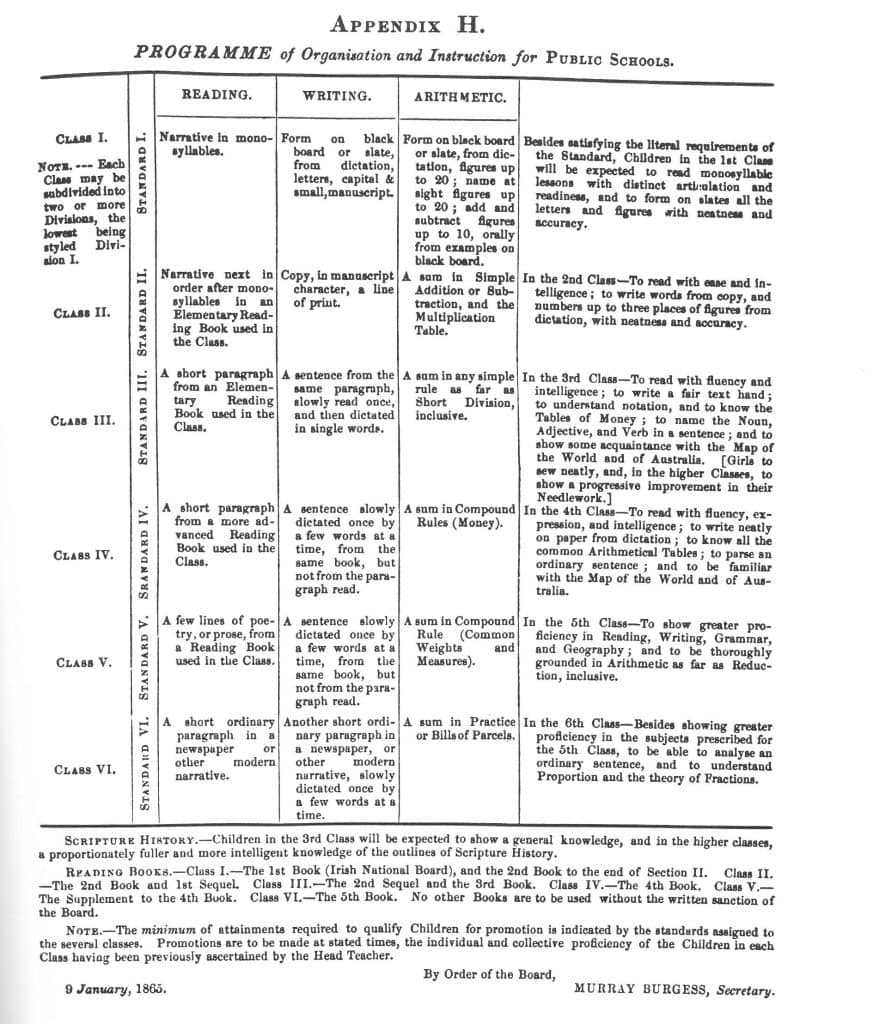

Partly, it’s to avoid sectarian conflict between Protestants and Catholics. But it’s also partly because they are really clearly graded from infants to grade 6, and it’s really clearly marked out like how you get from one grade to the next grade. They’re also really easy to teach from, and that’s important because most people who are doing the bulk of the teaching were teenagers, most kids in public schools in Tasmania would have been taught in a room of 40 to 60 students.

00:05:27 Speaker 2

And they would have been taught by a pupil teacher who was between the ages of 13 and 18, and the only reason that only way that kid is going to be able to teach other kids is if he’s teaching to the textbook.

00:05:36 Speaker 3

And it’s quite a plain looking publication. It’s, I mean, I’m not sure what colour it would have been originally, but it looks like it would have been quite cheaply bound.

00:05:46 Speaker 3

Yeah. What do you make of it?

00:05:48 Speaker 2

Ohh it is totally cheaply bound. There’s barely any illustrations in it. This is one that is for.

00:05:53 Speaker 2

The 4th class. So you this would be for like an 11 year old. There’s no illustrations at all. This is the generic 4th book of Lessons. So this was on Natural History, descriptive geography, miscellaneous lessons, practical economy. And there’s just like, virtually there’s not really a single picture in here.

And there’s no maps for Geography.

00:06:15 Speaker 3

And what would they have been learning about their own country, Australia at this point in time?

00:06:22 Speaker 2

Very, very little. There is a tiny section here on New Holland, which is what Australia is called. Let’s see what the publication date is.

00:06:31 Speaker 2

OK. So the publication date is 1849 and there’s a tiny section on New Holland. And so if you were an 11 year old child reading this, you would have read that in Van Diemen’s Land and in NSW, the greatest part of the settlers are men who were wicked in their own country and become still more so here from the influence of bad examples amongst them. And then you would have read the children of such parents are not likely to be brought up to any Good.

00:07:00 Speaker 2

And the consequences? We are told that it is quite a rare thing to meet with an honest, well conducted man in the colony and that robbery and murder and all the most horrible crimes are constantly being committed. So all you would learn is that your parents are bad, that you were bad and that you were doomed to badness?

00:07:18 Speaker 3

How long did they use these textbooks for?

00:07:20 Speaker 2

They were in use actually to prior to the establishment of compulsory public education. There’s accounts in Jane Franklin’s journals of going to pick these up to bestow upon deserving young children. You could imagine how grateful they would have been for that.

00:07:35 Speaker 2

And that would have been in the 1830s and 1840s. So they were being used until 1885. So that’s 50 years.

00:07:43 Speaker 3

Let’s have a look at another one. So now we’ve got the Tasmanian readers. So what sort of a year are we talking about now?

00:07:50 Speaker 2

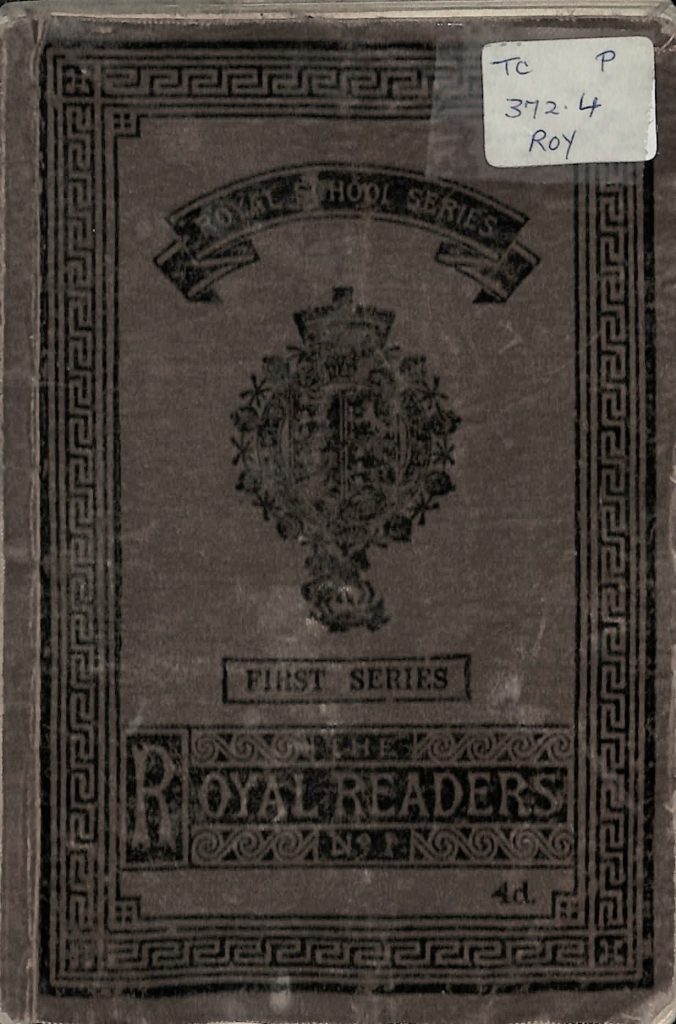

Now these ones were being produced until the early 1940s, but they started, these are A version of what called the royal readers and the royal readers replaced the Irish national readers they came into use in the 1880s.

00:08:04 Speaker 2

We don’t have a lot of copies of the royal readers here, but the Tasmanian readers are basically the royal readers printed with Tasmanian end papers. So these were again, these were produced in Britain. They were ordered from Britain, but they were printed with special covers and printed with special end papers to say they were for Tasmania. This one is great because it has the names of the boys who used it.

00:08:24 Speaker 2

One’s Richard Cook and one is I Engliss, so that they’ve stamped their names.

00:08:31 Speaker 2

All over the front.

00:08:31 Speaker 3

It looks it looks very loved.

00:08:33 Speaker 2

I’m not sure if it’s so much loved as it is abused.

00:08:36 Speaker 3

And interesting to note on the first page is a a nice big crown.

00:08:41 Speaker 2

And these ones, like the Irish national readers, these were still intended to to instil in children like a a basic sense of morality. And the idea is is still to sort of drill into especially.

00:08:55 Speaker 2

Little boys the.

00:08:56 Speaker 2

Proper way to behave, and there’s a lot of anxiety if you read the Tasmanian newspapers about.

00:09:01 Speaker 2

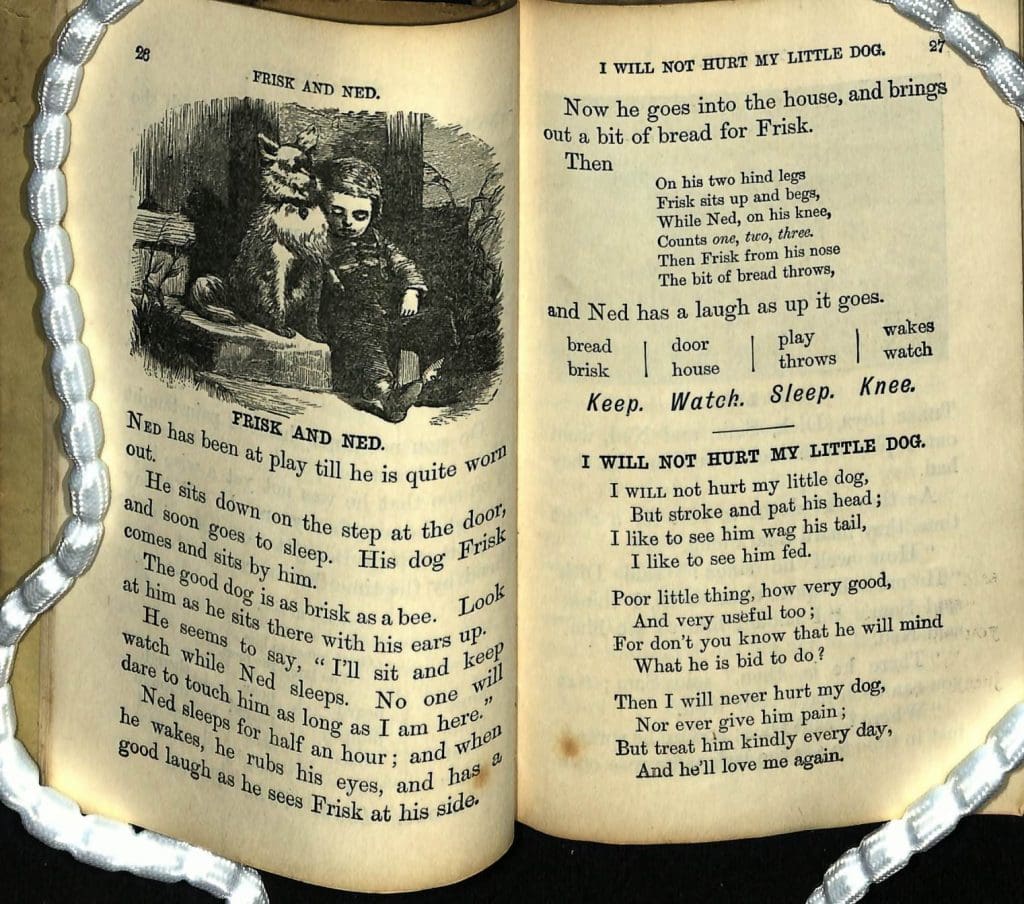

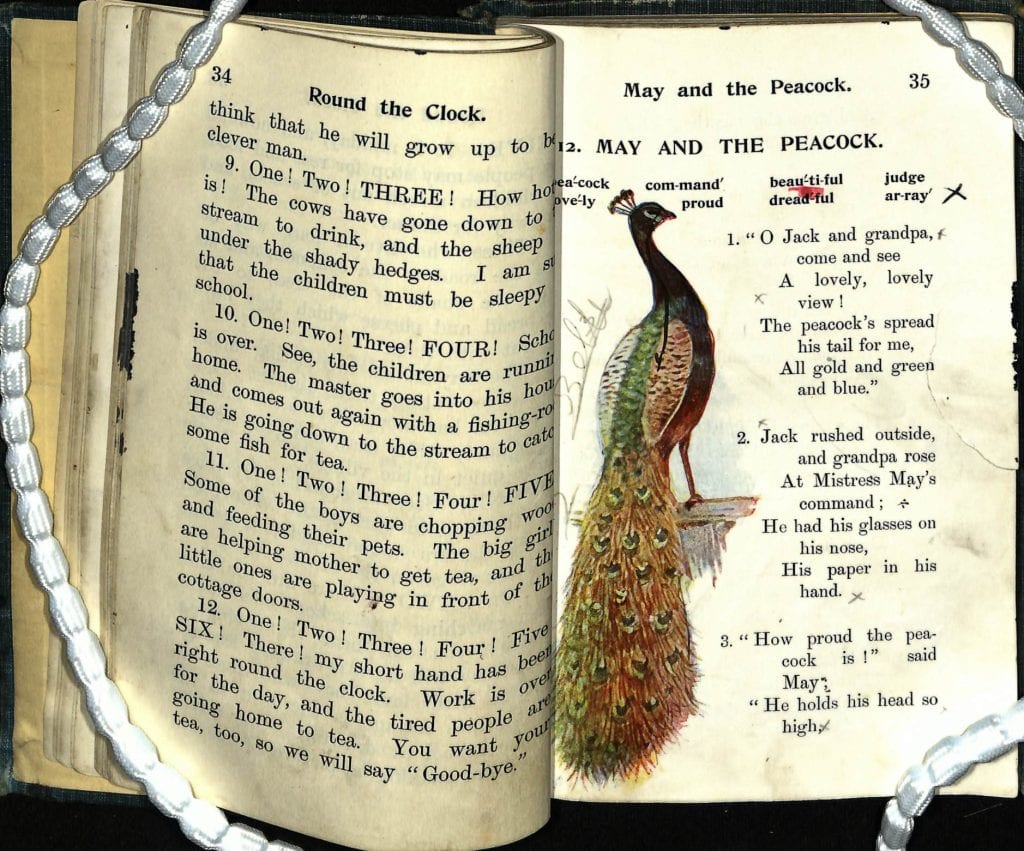

Wild school children roaming the streets and they need to be corralled and brought into the schools and taught manners. This is this is a good one and the great thing about this book too is that you can actually see where the little boy has marked it up so you can see where he would have stopped reading out loud in the class.

00:09:16 Speaker 2

These are targeted towards younger children, so you have lists of vocabulary at the front of each lesson. Instructions how to on how to pronounce words. If you were to do a history of Tasmanian childhood through these books, be a fairly pretty fascinating account of of.

00:09:35 Speaker 2

What children were taught was important in the public schools.

00:09:39 Speaker 3

And again not.

00:09:41 Speaker 3

Encouraging independent thinking at all or learning about their own country.

00:09:47 Speaker 2

Well, you get there. There’s a there’s a real arc that you get later on at the end of the 19th and the early 20th century, there’s a push towards more progressive education and teaching children to think for themselves a little bit more. And part of that is also making the textbooks more beautiful to look at.

00:10:07 Speaker 2

But what’s interesting there is that you actually see the influence of European educational thinkers who are still being used today.

00:10:16 Speaker 2

So you get more influence. People like Joseph Freud Bull and Maria Montessori, and people were talking about the the children need to be encouraged to learn, instilled with the love of learning. So you’re getting more of that at the beginning of the 20th century and the early 1900s. And you’re getting away from the idea that children need to be warehoused and reformed.

00:10:38 Speaker 2

And there is a push to have more Australian content reflected in the books. But what’s interesting is that the way that that content is presented to children.

00:10:50 Speaker 2

And it’s presented very much as Australia is part of the British Empire and that your loyalty and your affinity should really rest with Britain first and foremost. And that’s not at all unusual. That’s the whole purpose of public education throughout Europe, throughout Britain, throughout America.

00:11:09 Speaker 2

In the late 19th century, it is to make children citizens of a nation or an empire.

00:11:16 Speaker 2

And Australia is an interesting case after federation because it’s a separate country, but it’s still part of the Commonwealth and expected to go fight British Wars. So you do end up with books like the royal readers. And then like, for example, the Longmans British Empire, readers, all of which have this, really.

00:11:36 Speaker 2

Not so subtle message behind them, which is that the British Empire is a force for good in the world, that it’s normal that it’s natural that certain peoples should be subjected to it and that small children should grow up to love it and defend it.

00:11:51 Speaker 1

The ABC’s Georgie Burgess with archivist Anna Claydon in the History room, speaking softly in Hobart’s library, having a look through some textbooks using classrooms during the late 1800s, and you’ll hear more from that next week.

“Boisterous Rudeness” and “the Fiercest Wild Beasts” – Irish National Readers and the Tasmanian Curriculum, 1869-1885

The Tasmanian curriculum in 1869 was not supposed to excite children’s curiosity, or to spark their creativity, or even to foster a love of learning. In the eyes of some Tasmanians, the main purpose of public education was clear: to warehouse rowdy working-class children, keep them away from respectable people, and teach them some manners. As the Tasmanian Times pointed out on the 7th of July,

“…a boisterous rudeness is the characteristic of most school-children in and around this city, and it is not difficult to perceive how habitual ungentleness … in the child may grow into the offensive ruffianism which makes our streets dangerous at night.”

“THE COLONIAL BOY.” The Tasmanian Times, 7 July 1869: 3

Nineteenth-century administrators looked to religion to turn boisterous children into respectable citizens, but that presented its own problems. Tasmania was a multi-ethnic community with a large Catholic population, largely descended from Irish convicts. Sectarian tensions between Protestants and Catholics ran deep, sometimes bubbling out into violence. One of the biggest episodes was the Chiniquy Affair in 1879, when the Southern Tasmanian Volunteer Artillery was called out to suppress a riot outside the Hobart Town Hall sparked by visit of a controversial ex-Catholic priest from Canada, Charles Chiniquy. If public schools were going to reform “habitual ungentleness” and erase “offensive ruffianism,” then they were going to have to bridge this divide.

The solution in Tasmania was one that had been adopted in many other British colonies –to use Irish National Readers. The Irish National Curriculum, put together in 1831, was supposed to help solve the bitter sectarianism in Ireland under British rule. The majority of the Irish population was Catholic, but power, land, and wealth were concentrated in the hands of a Protestant Anglo-Irish elite. Most Irish Catholics worked as tenant farmers and were forced to pay rent, often to absentee Protestant landlords. The idea of the Irish National Curriculum was that if Catholic and Protestant children learned together, they might learn to live together. The cheaply printed Irish National Readers were very careful to favour neither Catholics nor Protestants – they were designed to be bland, uniform, and so basic that nobody could object to them.

Sadly, the curriculum alone couldn’t solve what came to be known as the “Irish Question,” as poverty, starvation, mass emigration, political dissent, rebellion and sectarian violence defined nineteenth-century Irish history. Millions left Ireland aboard emigrant and convict ships in the Irish Diaspora (especially during the Great Hunger of 1845 – 1849 which killed a million people) and thousands of convicts came to Tasmania, transported for everything from raising revolution to stealing food. But fascinatingly, almost everywhere within the British Empire that the Irish landed, the textbooks followed, and they formed the basis of the curriculum in Australia and in Canada – because they were cheap, they were available, and they were non-sectarian.

So what did children actually learn?

The curriculum from 1869 to 1885 was strictly the three “Rs” – reading, writing, and arithmetic. Spelling, grammar, geography, history, singing and sewing (for girls) were eventually added. Children were separated into classes from I to VI based on their accomplishments, and teaching was strictly “to the test.” There were annual exams, usually around Christmas, and they were reported on in the newspapers. These reports made the schools sound positively idyllic, such as this account of the examinations for New Town Public School in 1870:

After cheers for the providers of prizes, visitors, teachers and successful competitors, the children retired to their respective play-grounds, and having amused themselves by indulging in cricket &c, till evening, a pleasant day’s proceedings were brought to a close by a tea party in the school-room, which was tastefully decorated, and the children were dismissed for the holidays.

“CHRISTMAS EXAMINATIONS.” The Mercury (Hobart, Tas. : 1860 – 1954) 29 December 1870: 2.

The reality was probably much less fun. Much of the instruction was done by pupil-teachers – teenagers between the ages of 13 and 18 who were put in charge of up to 60 students (and our next blog, by librarian Anthony Black, will examine this in greater detail). According to Derek Phillips and Michael Sprod’s landmark history of Tasmanian education, this system “regimented the lives of children and made the task of the teacher one of unremitting misery.”

To make matters even worse, the children were probably exhausted all or part of the time. They went to school six days a week (Monday to Saturday) from 9 am to 4 pm, with a 2 hour break at lunch. In Hobart and Launceston, children had half holidays on Wednesday and Saturday. Outside of school, they were often expected to work – on family farms, in the home, minding children, helping neighbours, or working for wages (e.g. fruit and apple picking in season with their mothers, or harvesting with their fathers and uncles).

In any event, the readers themselves were basically unreadable – most students never passed out of Grade IV. You can have a look for yourself – Deakin University has digitized a number of the Irish National Readers, and there are several in our collection in the State Library (all of which came from the Prisoner’s Barracks in Hobart).

I was looking for a good excerpt to share with you – just to show how dense and difficult the textbooks were for children to read – and I stumbled across this passage in a geography lesson in the Fourth Reader. It describes Van Diemen’s Land and New South Wales as ,

“neither a pleasant nor a safe country to live in, for the greatest part of the settlers are men who were wicked in their own country, and become still more so here…. The children of such parents are not likely to be brought up to any good … It is better to live among the fiercest wild beasts than amongst wicked and hard-hearted men.”

One can’t help wondering what effect that passage would have had on a twelve-year old Tasmanian child – to find your home described as unsafe, your family as wicked, and yourself as ‘born bad.’

“Make them delight to exercise their power of reading” – Royal Readers, 1885-1904

Tasmanians were all too aware that the public education system needed improvement. In fact, the systems and curricula adopted elsewhere were regularly reported on in the local newspapers, because public education was a hugely important question around the world, as new systems were trialled from Great Britain to France to Russia. While all these systems were different, they shared a single goal – to use public education to make individuals into citizens of the nation, with an emotional attachment to their country that would trump class, religious, regional, and ethnic identities.

When the Tasmanian Board of Education replaced the Irish National Readers with the new Royal Readers in 1885, they also adopted this agenda. The Royal Readers were more accessible, with more illustrations, and excerpts from literary and historical texts. The biggest difference was that they deliberately tried to get children excited about reading, pointing out to teachers that their goal was to get “children to take a real interest in what they read, and to make them delight to exercise their power of reading.” Natural History and the “incidents and common things of daily life, by which children are most likely to be attracted” formed key parts of the curriculum. Books for young children had songs to be memorised, samples of handwriting, guides to pronunciation of new words, all of which were wrapped up in moral lessons (such as “I will Not Hurt My Little Dog.”)

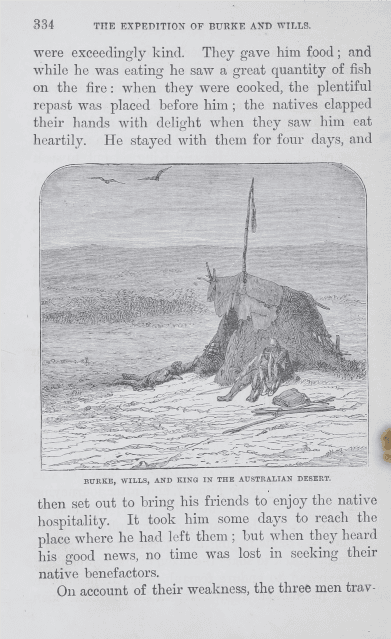

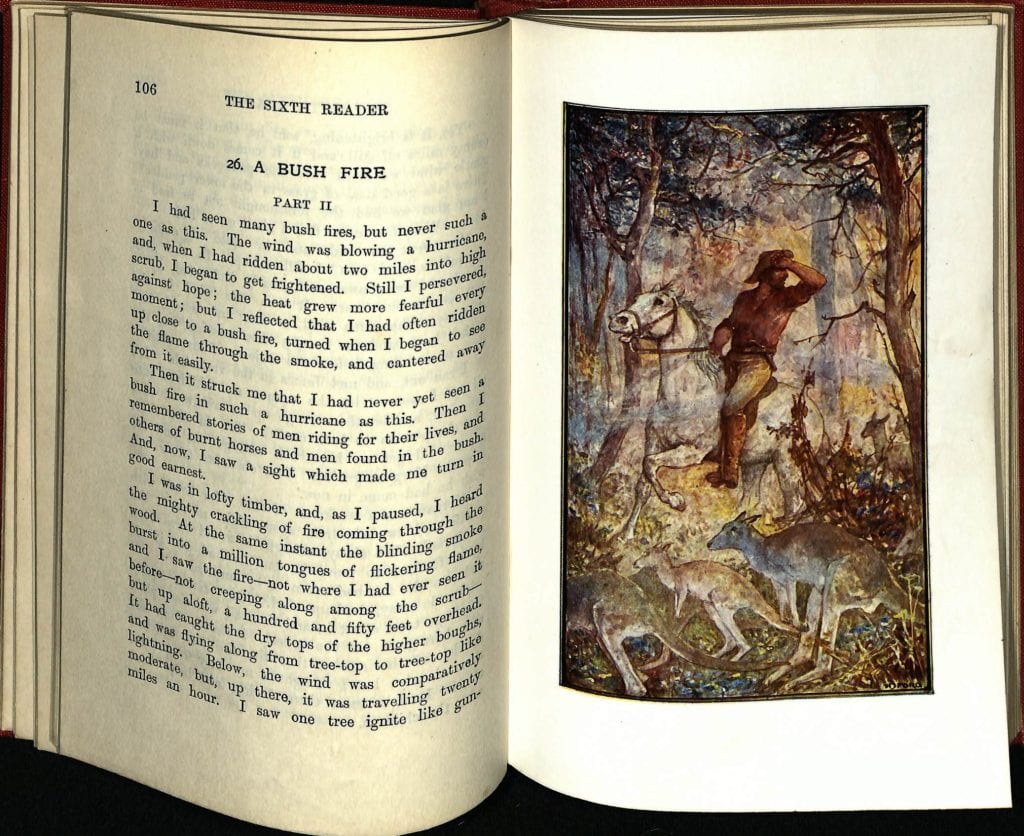

The readers had another agenda: they also taught children to believe that the British Empire was normal, natural, and inevitable, to take delight in its triumphs and to learn moral lessons from defeat. History was presented as a series of adventure stories that took Britons around Europe and the world – as this online exhibit from Deakin University points out, “The Royal Readers were unabashed in their celebration of war and the expansion of the British Empire.” As Australian content was added, it fit into this agenda. By the end of the century, the readers included a whole final section on Australian exploration, using explorers as examples of intrepid heroes of a new nation, from Matthew Flinders to Burke and Wills (and in which Aboriginal people were caricatured, marginalised, or erased).

Despite the shift to the Royal Readers, between 1885 and 1895 little else seemed to change in Tasmanian public schools, though the curriculum did expand to include history, elementary science and drill. The Inspectors’ reports made it very clear – Tasmanian public schools had a long way to go. Grammar was taught in schools, but poorly, and the emphasis was still on rote learning. Most singing was taught by ear, and very few students learned how to read music. Most schools didn’t attempt drill or physical education of any sort (though they were compulsory parts of the curriculum after 1887), and there was almost no instruction in elementary science, though history, geography and physical geography were improving.

W.L. Neale and the ‘Wonderful Possibilities of the Human Soul’

In 1904, a man named William L. Neale (an inspector of schools in South Australia) wrote a scathing report which claimed, as one newspaper summarized, , ‘our teachers can’t teach, our inspectors can’t inspect, our Director can’t direct, our copybook contractor cheats us, and our Public Works can’t build schools.’ Neale was appointed by the Premier W.B. Propsting as Director of Education in 1905, which marked a turning point in Tasmanian educational history – and a radical new idea that education should unlock children’s potential and excite their curiosity.

Neale started many reforms to Tasmanian education, including teacher training, early childhood education, public health and physical education – all of which we’ll talk about in later blogs. But he was also committed to improving the curriculum as a whole. Neale was a “New Educationist,” inspired by the work of European educators like Josef Froebel and Maria Montessori, and by the new science of psychology. His goal wasn’t to contain wild children or to erase convict stains, but to make children into independent, critical and creative thinkers – a truly radical idea. As Neale put it, a “real education” system,

‘must develop every side of a child’s nature… it prepares him for all his ethical, moral, social and civic relationships. It gives him the power to think rightly on all questions and to act rightly in all relationships…..’

Quoted in Phillips, Making More Adequate Provision, p 86-87

On 29 October, 1906,Neale wrote a long article in the Mercury on the “Insufficiency of School Books.” both to clear up a number of myths about his various proposed reforms, and also to make it clear that he was pursuing funding for new textbooks, and also to make them free to poor children. This prompted some parents to write to Neale with suggestions. Mrs Ida McAuley wrote in October of 1906 that she’d ordered some books from England for her own children (“Home and Abroad,” “Gateway to History,” and “Steps to Literature,”) and she told Neale, “I am delighted with them…. All the books are lavishly and beautifully illustrated…. I think they should be more widely known.” (ED9/1/213, Ida McAuley to W.L. Neale, 29 October, 1906).

The books were ordered from the UK and printed with special Tasmanian endpapers and covers. These included the Tasmanian Readers, which were basically Royal Readers with different covers. We have a couple in our collection – and you can see how this one, (owned by Richard Cook and D. Sutherland), was used by at least a few children in its long life! This particular book is fascinating, because you can see the evidence of this little boy’s lessons literally written into the book – the ticks against new words that he learned, the marks to separate words into syllables, or perhaps to mark where he was to stop reading out loud.

The curriculum also included the British Empire Readers – which, the publisher Longman’s & Co told Neale, needed to be ordered through their local agent in Hobart “as it is our policy to support local booksellers wherever possible.” These were brightly illustrated, sturdy copies with attractive covers – with the clear message that the British Empire was a force for good in the world, which Tasmanian children should admire and protect. So the British Empire Reader – which was locally printed and beautifully produced – were packed with stories of imperial battles and intrigues in South Africa, Afghanistan, and India, written by Arthur Conan Doyle, H. Rider Haggard, Charles Dickens and Robert Louis Stevenson. If Neale’s goal was to create free-thinking young people, it’s not likely that a solid diet of Boy’s Own Adventures did the trick. As for Australian content, it was surprisingly limited, though this particular volume did include a rather exciting account of a bushfire.

Neale’s educational reforms were not welcomed with open arms in Tasmania – his own personality was his worst enemy. He was determined to modernize Tasmanian education, but he was also often rude and disrespectful. Between 1907 and 1909, he was the subject of three royal commissions, prompted by complaints from teachers whom Neale had censured. While Neale convinced two of the three commissions that the complaints were unjustified and vindictive, ultimately, he was forced to resign in 1909. The historian Betty Jones argued that, “his resignation was a tragic blow to Tasmania where education was forgotten as personality and prejudice were allowed to preside.” (School Days, School Days…. p 92), while Derek Phillips suggested that Neale saw himself, and should be seen, as a zealous missionary whose views on education ‘betray[ed] the missionary’s intolerance of those who cannot keep up and who fall by the wayside and … the self-assurance of the spiritually blessed.’ (Making More Adequate Provision, 109) .

Within the first fifty years of compulsory education in Tasmania, there had been a huge change in the books children read – from the Irish National Readers designed to bore the exhausted students into a kind of bland social uniformity, to specially produced and attractive volumes that tried to excite children’s natural curiosity and foster a love of reading, of learning, and of the British Empire. Each shift in the curriculum reflected its own historical moment, its preoccupations, its goals, its blind spots.

Stay tuned for more blogs on the history of 150 Years of Public Education – on Teachers & Teaching, Public Health in Schools, Kindergarten, and more! If you’re interested to learn more about anything you’ve read here, check out these suggestions!

Further Reading

Explore 150 years of public education in Tasmania

What’s Online? Nineteenth Century Children’s Education and Children’s Literature

For a terrific overview of the history of education, check out this fabulous article in the Encyclopedia Britannica on Western Education in the nineteenth century, which covers the developments in state education in Germany, France, Britain, Russia, the US, and the British Dominions (including Australia and Canada).

The State Library of Victoria has an amazing Guide to Children’s literature, and a wonderful Children’s Literature Research Collection. You can also watch a video about their collection with the Research Librarian Dr Juliet O’Conor here.

The State Library of Victoria also has a dedicated guide to Readers and Textbooks: School and Education History in Victoria: https://guides.slv.vic.gov.au/education/readers

Deakin University has a collection of digitized nineteenth century school readers, which you can find here as a part of the Australian Schools Textbook Collection. There are also great short articles and timelines. The content is focused on Victoria, but there are a few Tasmanian examples as well: http://fusion.deakin.edu.au/exhibits/show/textbook/intro

Education in Tasmania

Michael Sprod, ‘Education’ in Alison Alexander (ed), Companion to Tasmanian History. Centre for Tasmanian Historical Studies (2005), University of Tasmania (2017) http://www.utas.edu.au/tasmanian-companion/biogs/E000320b.htm

ED31: Inspectors’ Reports on Staff, Teaching and Organisation of Schools, 1890-1970

ED9/1/213, General Correspondence (3), Education Department, “887/1906. New readers.”, 1906-1914

The Irish in Australia and Tasmania

If you’re keen to learn more about the Irish Diaspora in the nineteenth century and the many ways in which it shaped Tasmania (and the world) you can start with some of these great books – and also check out the link at the bottom for all the Irish History resources we have at Libraries Tasmania.

R.F. Foster, Modern Ireland, 1600-1972 New York: Penguin Books, 1989

Plus these resources on Irish History across Libraries Tasmania

Good Afternoon

My 5 year old grandson is having a grandparents day soon and the theme is their grandparents early schooling

I started school in 1958 -does the library have any copies of the early readers school used in the period 1958 to 1965

Kindest regards

Darien Males

Dear Darien, I am so sorry that we were not able to reply to your query more quickly. I have found some examples of early readers from various time periods in our collections. The following search contains several examples from the 1960s. https://librariestas.ent.sirsidynix.net.au/client/en_AU/library/search/results?qu=SERIES%3D%22Teaching%22&qu=SERIES%3D%22Aids%22&qu=SERIES%3D%22Centre%22&qu=SERIES%3D%22publication%22&qu=SERIES%3D%22%3B%22&rw=12&te=ILS&lm=RTA-OS&isd=true

There is also a series called ‘the Tasmanian readers’, which was published between 1900-1940. The archival series AB713 – ‘Teaching aids centre prints’ may also be of interest. It includes a lot of imagery of schools from the 1950s-1970s, as well as photographs taken for use in lessons during this time period.

I hope this is helpful to you. If you need further assistance, you can send a question to our research service using our research request form: https://sltas.altarama.com/reft100.aspx?key=Research