Esther’s Story, Part One: The Whaler’s Log

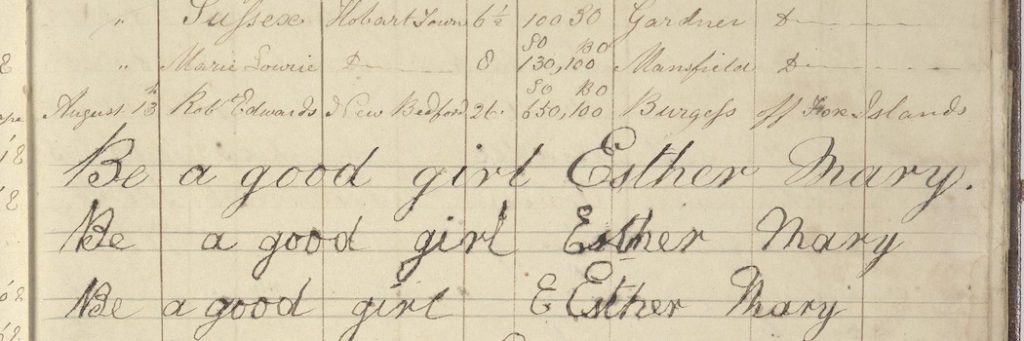

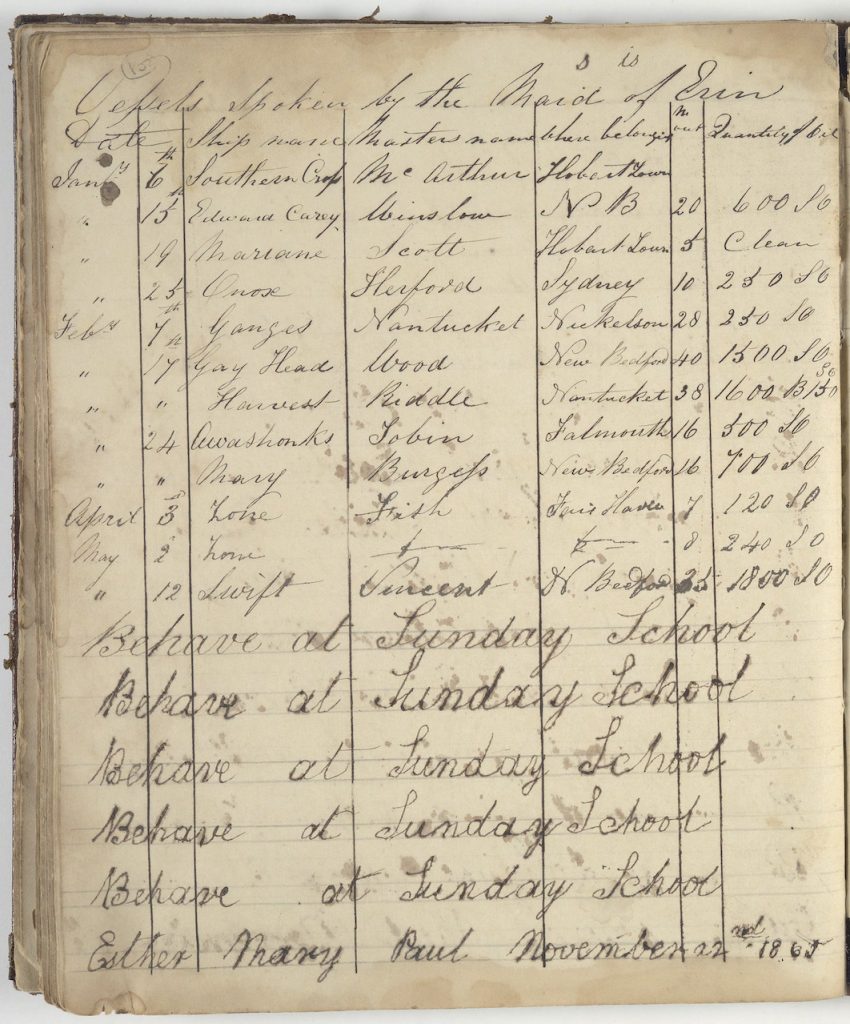

In November of 1865, a five year old girl named Esther sat in a house in Sandy Bay, writing lines in a small, leather-bound book. Some days, she had geography lessons. Some days, she was in trouble. Some days, she just needed to memorize her new address. Two months came and went, and the little girl wrote line after line. Her notebook had once belonged to her Uncle William, and recorded his whaling voyages to the Pacific Ocean and the Timor Sea. In the spaces in-between the stories of whales and gales, little Esther did her school work. So did her Aunt Charlotte, who copied out poems and ballads for the little girl to memorize. Aunt Charlotte knew that logbook well, for it was the record of her own honeymoon at sea, nine years earlier. Now it became a part of a different family story – of tragedy, loss, love, abandonment, and survival.

Esther’s Story is actually the story of three nineteenth-century women: Esther Mary Paul (Lithgow), her mother Cecilia Eliza (Rowland) Paul, and her aunt Charlotte Ann (Rowland) Jacobs. Over Family History Month, we’ll follow these women through three blogs and fifty years of their lives, using digital collections together with library and archival resources. It’s a tale of adventure, improvisation, and resilience, but it’s also something else. It’s a reminder – of how our own historical present can change how we think about the past. Read on to discover more.

Finding Esther – Family History Month, August 2019

A year ago, and in a different world, we found Esther in the archives. In August, 2019, we were looking for a story for National Family History Month that highlighted the Tasmanian Names Index, our online index of over a million records. My colleague Jessica Walters wanted to follow up on an old idea of ours – using the Names Index to track nineteenth century Hobart whaling families.

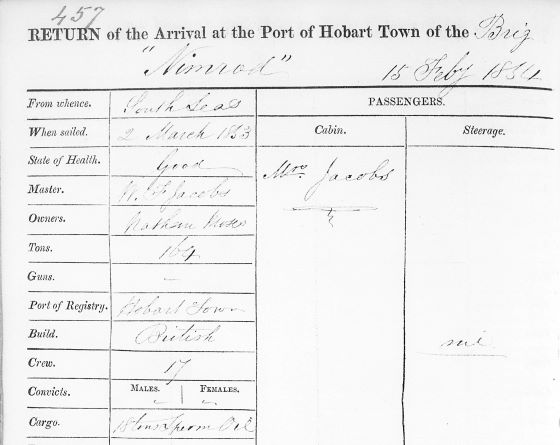

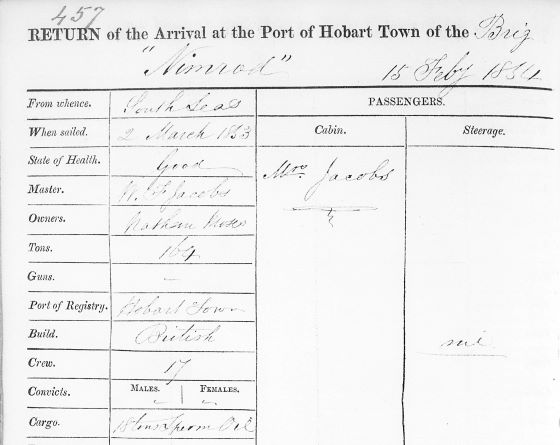

If you go through the records of ships arrivals in the port of Hobart (MB2/39), every so often you’ll find women and children listed as passengers on whalers, with the same surname as the captain. Once you start looking, there are lots of them, more than you would imagine – Mrs McArthur, Mrs Robinson, Mrs Reynolds, and many others – coming and going to and from the South Seas, New Zealand, Hawai’i, Timor, and further.

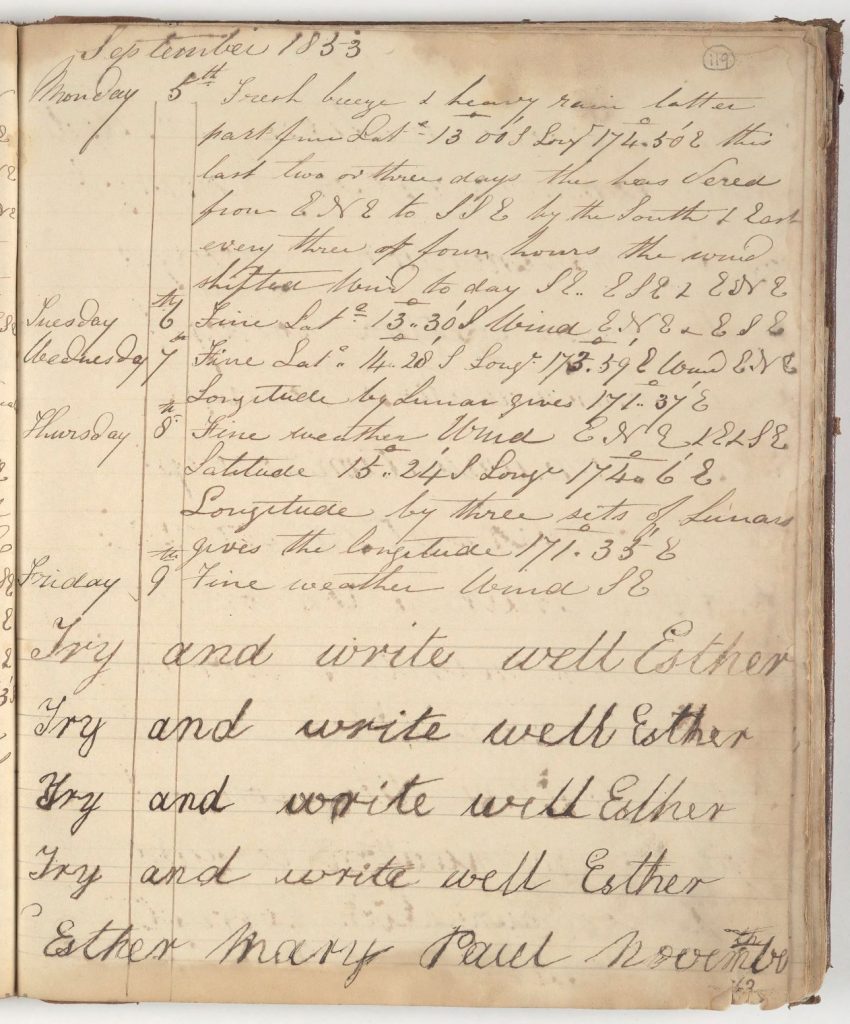

Luckily, the Reprographics team had just digitized some of the Crowther whaling logbooks (CRO82). I flicked idly through the list and one sprang out at me – a logbook that included both a voyage to Bering Strait and three voyages under Captain William Jacobs. In the log of the Nimrod in 1853, we found lines and lines of a child’s handwriting, crammed up against poetry, limericks, and accounts of the bloody business of hunting whales. Each page was signed by a little girl – Esther Mary Paul.

Who was Esther? How old was she? Why was she writing lines in this logbook? Was she being educated or punished? Or both? Was she on the voyage of the Nimrod ? There was no child listed on the ship’s arrival record or departure documents. So how did little Esther end up writing in the logbook?

Esther was a compelling little mystery, but one that I couldn’t pursue – until the pandemic hit, and the library closed, and the lockdown began. In April of 2020, I found myself educating my own five year old at home, with my own husband at sea for an unknown period of time. It seemed natural to return to the story of the logbook, and to track Esther and her seafaring family down, using the resources I had at hand. The story that I found was amazing, literally spanning huge tracts of space and time, and it’s difficult to know where to start. So let’s start at the beginning – long before little Esther was born. Let’s start with Uncle William’s logbook.

The “Hen Frigate” Nimrod: Captain Jacobs takes Mrs Jacobs to sea, 1853

In 1853, a wedding took place in Battery Point. Charlotte Rowland, spinster, and William Forbes Jacobs, master mariner, were married on 15 February at Charlotte’s father’s house in Kelly Street. If the newlyweds walked down the sandstone Kelly’s Steps, they would have stepped out onto New Wharf (now Salamanca Place), bristling with the masts of dozens of whaling ships. Among the vessels would have been the whaling barque Nimrod, and a few weeks later, the newly married couple would set sail in her for a whaling voyage to the South Seas. They would not return to Hobart for a year.

Why did Charlotte go to sea? Why did any women leave the safety of the shore for months aboard a whaling ship, exposed to gales, high seas, privateers and enraged whales? Theirs was a bloody, smoky, brutal world, as the paintings of William Duke (in the Allport Library and Museum of Fine Arts) attest.

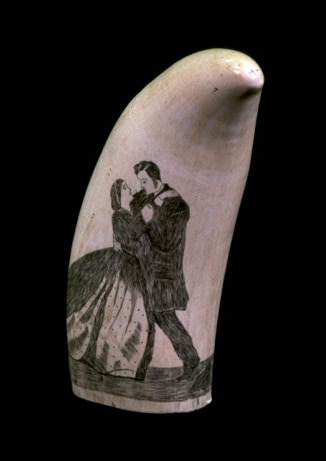

A woman on board a whaling ship was a rare thing in 1853. As whale stocks dwindled around the world, whaling voyages became longer and longer, and in some ports, like New Bedford, couples could be separated for up to five years. Our scrimshaw collections help tell that tale – the teeth, jaws, baleen and bones of dead whales, inscribed by unnamed men with the images of women they held in their minds. When and if they made it home, those pieces might be displayed for years in the family home – and perhaps there were some arranged around the room where little Esther copied her lines in her uncle’s logbook.

As the only woman aboard the ship, Charlotte Jacobs would have occupied a strange position – both as an adventurous soul and as a bastion of Victorian-era domesticity. Women like Charlotte walked the line of respectability, between being thought “unladylike” and being devoted wives compelled to go to sea by love and duty. Many women, however, decided that the chance of adventure with their husbands was better than waiting at home, with only their thoughts for company.

At sea, a whaling wife might experience a truly multicultural world, perhaps for the first time in her life. Tasmanian whaleships carried crew that included Tasmanian Aboriginal men and the sons of Tasmanian colonists, working alongside Maori, Pacific Islanders, Americans, British, Irish, and Scots and others. On the voyage of the Nimrod, Captain Jacobs shipped aboard at least four crewmen from Vanuatu (see below) – but without a crew list, we don’t know where the rest of the sailors hailed from. For some women, the experience of spending months at sea with dozens of men from around the world was shocking. For others, it was exhilarating. We don’t know how Charlotte Jacobs felt – and we also don’t know how the crew felt about her.

Wherever they came from, the crew did not always welcome the captain’s wife. “Having a woman aboard changed the lifestyle of the crew – their language, the tales they told, their dress, their manners…” according to the folklorist Horace Beck. Superstitions about women at sea bringing bad luck, even disaster to a boat, were prevalent and widespread in the nineteenth century – and many whalemen avoided shipping out on what were called “hen frigates.”

What is certain is that life for the new Mrs Jacobs, like many of her compatriots, would have been hard. While they would spend most of their time in the cabin, and away from the bloody business of ‘cutting in’ and ‘trying out,’ still their hair would have smelled of the greasy black smoke of the trypots, the smell of dead whale would have been lingering on every pore and surface, and they were still at risk of injury, storms, and shipwreck. Other whaling wives from Australia, New Zealand, America, and Britain had to act as surgeons, as midwives, and sometimes as diplomats during these long voyages. It must have been a deeply exciting, often terrifying experience – especially if you knew that you weren’t the first Mrs Jacobs to attempt it.

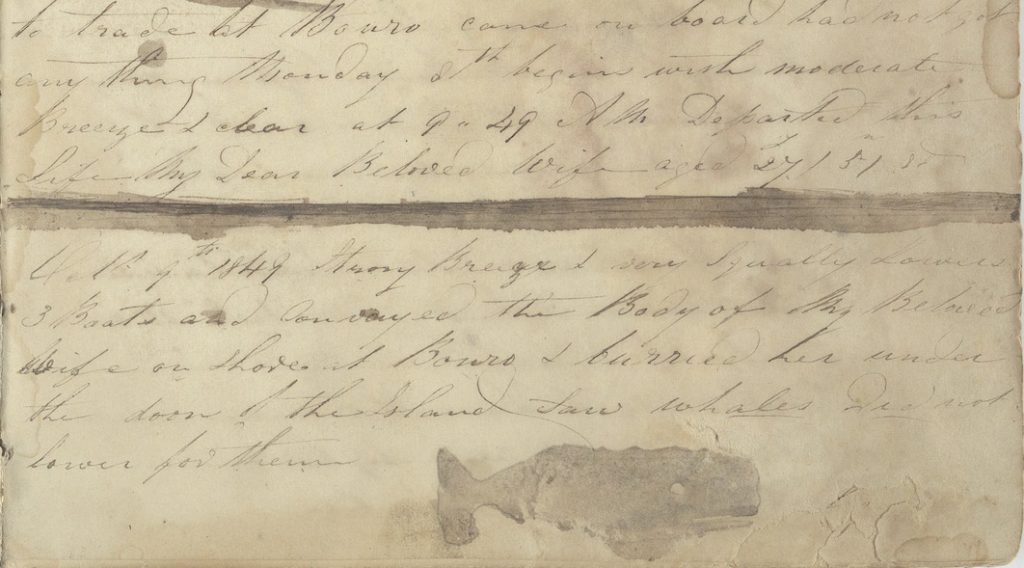

The Ghost of Amelia Jacobs

Captain William Forbes Jacobs was a man who liked to take his wife to sea. In 1846, he had married Amelia Holt in Sydney. She was 27 and had come out to New South Wales by herself five years earlier, after the deaths of her parents. Then William went whaling for a year – it’s impossible to know whether or not Amelia went with him. He left again in 1847 for a five-month cruise around the Bay of Islands in New Zealand. In 1848, he had to put down a mutiny on the Arabian. As soon as the court case was settled, William took Amelia with him to New Zealand and the Timor Sea, on what would be her last voyage.

After many months at sea, and on a page covered with drawings of sperm whales, Captain Jacobs wrote, “Monday 8th [October], begin with moderate breeze & clear at 9.49 AM Departed this Life My Dear Beloved Wife age 27. Oct 9th 1849, Strong Breeze and Very Squally Lowered 3 Boats and conveyed the Body of my Beloved Wife on shore at Bouro & buried her under the door of the Island saw Whales but did not lower for them.” In the four months that followed, ten more of his crew succumbed to dysentery, including the surgeon, who left behind a wife and two small children. The log of the Arabian ends with a lament – that “the last 16 Days saw Blackfish Porpoises Finback in great numbers the Ocean fairly covered with them but no Whales worse luck. To low spirited to write any further.” News of Amelia’s death was carried in newspapers in Sydney and in Launceston, as she was “deeply regretted by all who knew her.” Sixteen years later, William Jacobs would hand over the log to his second wife’s niece. He gave it to little Esther to do her homework.

“The Captain Not Expected to Live”: The Voyage of the Nimrod, 1853

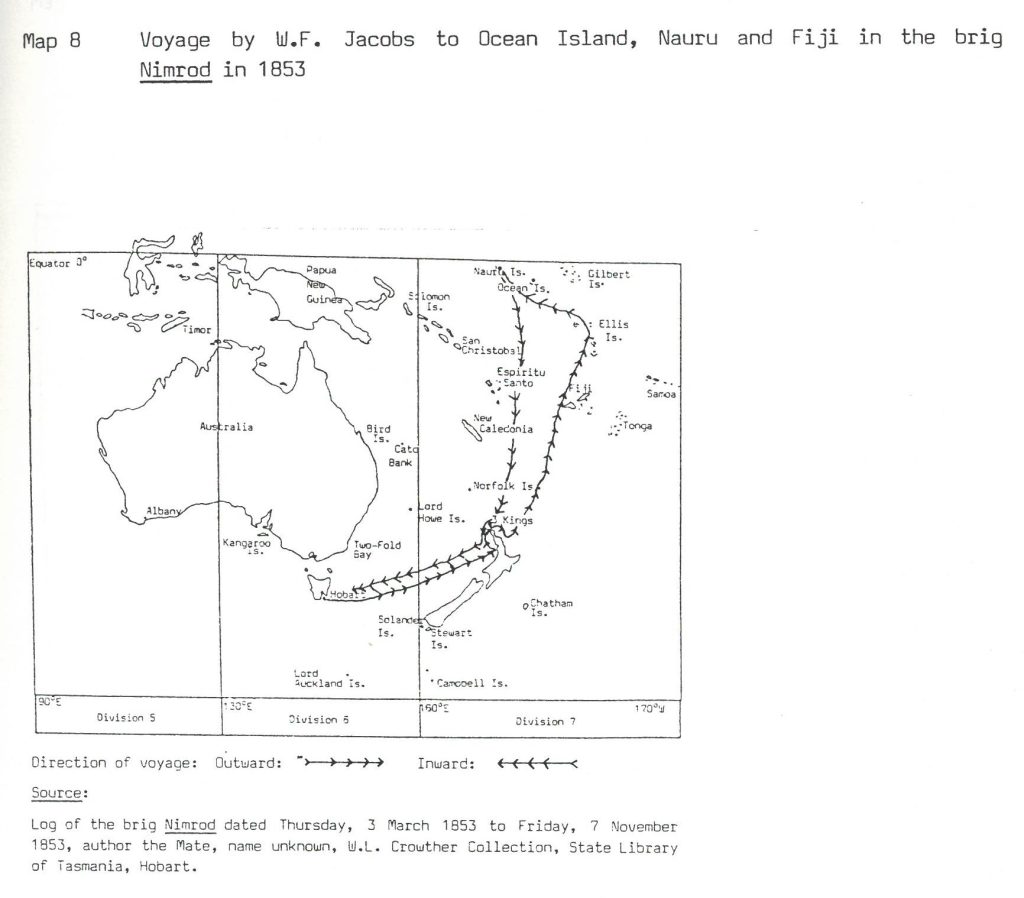

Four years after his wife Amelia died at sea, Captain William Jacobs married Charlotte, and took her to the South Pacific. In the same logbook that records Amelia’s death, you can trace William and Charlotte on their honeymoon voyage. Dr Susan Chamberlain reconstructed their track in her wonderful (and sadly unpublished) PhD thesis.

It would have been a difficult voyage, as the captain worked the crew through gale-force winds off the New Zealand coast to try out and stow down the oil from the whales they’d killed. In late May, the storms were so fierce that they put the tryworks out – the great iron cauldrons used to boil down the whale blubber before stowing it in barrels. They’re still dotted around Tasmania, relics of the old whaling days.

Whaler’s old trypot at ‘Maydena’ – Sandford – Elizabeth Wilson standing alongside. Tasmanian Archives, NS3195/1/1914

In June, the Nimrod was in Vanuatu, where they took on local men as crew, repainted the ship, filled her water casks and traded for boat loads of yams, coconuts, bananas, breadfruit, oranges, pineapples and “mummy apples.” We don’t know what else William and Charlotte might have been exchanging during these stops, but we do know that they were part of a much larger phenomenon – the transformation of the economies and ecology of the Pacific Islands (check out the marvellous work of Jennifer Newell for more on this fascinating topic).

The log also records a lost world – a world populated with whales, though their numbers were diminishing. Charlotte Jacobs would have seen “finbacks” or humpbacks, “killers” or orcas “in great numbers” and “blackfish” or pilot whales and sperm whales, but would have heard, too, how much fewer they were than in previous years. They saw no right whales, for by this time the southern population was virtually extinct because of commercial whaling. When they “spoke” other whalers, they would have heard of their long, multi-year voyages chasing after bowhead whales, as far north as the Kamchatka Sea and Bering Strait.

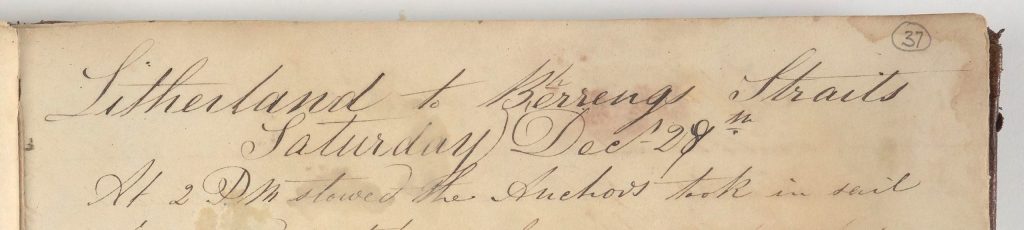

As a matter of fact, the log of the Nimrod is also bound together with the log of one of these other far northern voyages, the log of the Litherland in 1851 (it starts on page 37). Like most other Hobart whalers, though, the Nimrod didn’t go so far, and shifted her focus onto these other, dramatically declining, species.

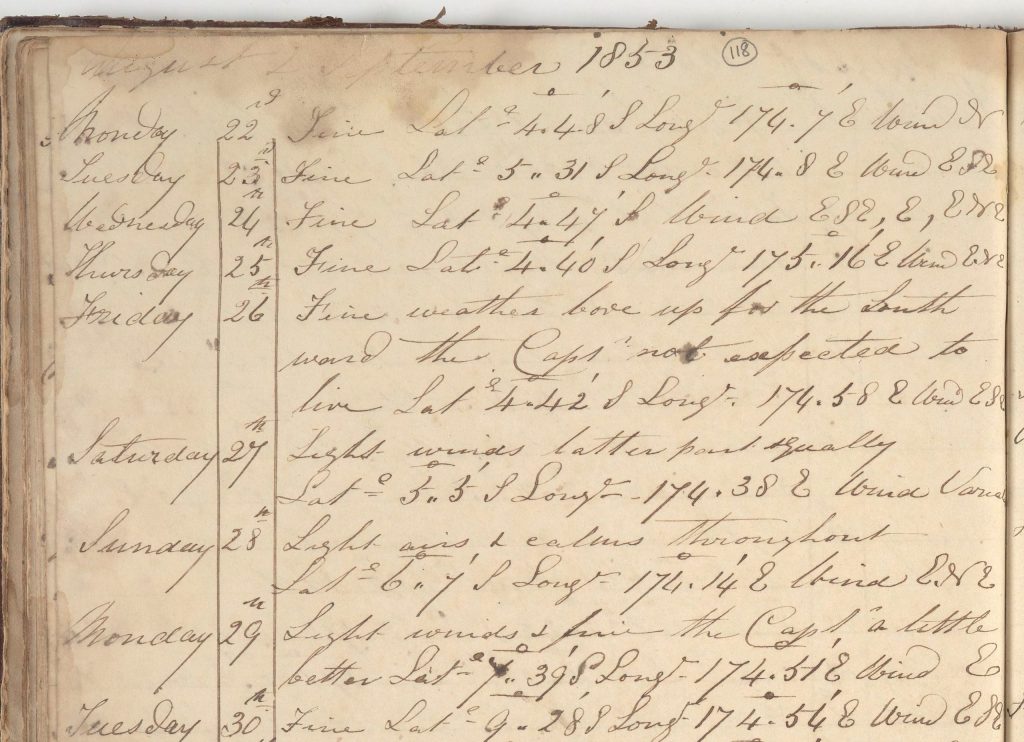

July and most of August passed as the Nimrod cruised the South Seas, while the mate recorded their position, the weather, and how many whales they saw and chased. But matters took a turn for the worse, for in the fine weather of the 28th August, he noted, “the Captn not expected to live.”

What had happened? There is no mention of an accident, the weather had been fine (for a change), but the Nimrod turned south, and within a few days, the mate noted, “the Captn a little better.” He writes nothing more about the captain’s condition, and on the very next page, the log breaks off, and little Esther takes over.

As to what happened, how Captain Jacobs recovered, we cannot and will probably never know. If the vessel was “spoken” by another whaler, news did not reach any Australian port before the Nimrod herself arrived in Hobart on the 15th of February, 1854. It was William and Charlotte’s first anniversary, and they were returning home with eighteen tons of sperm oil, and William Jacobs was at the helm.

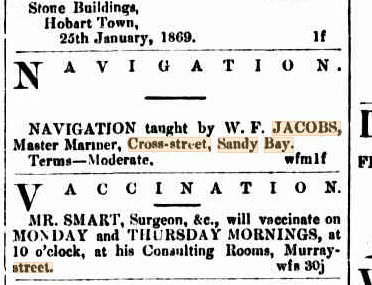

Nine years passed between the Nimrod‘s return in 1854, and when Esther began to write her lines in the pages of her uncle’s log. In that time, Captain Jacobs went whaling at least three more times – on the Nimrod (1854), the Maid of Erin (1854) and the Lady Leigh (1856). By the 1860s, you can find him taking the brig Union back and forth between Tasmania, the mainland, and New Zealand. Charlotte sometimes went with him, and in-between voyages, they stayed at her mother’s house in Cross Street, Sandy Bay. But then in 1865, his ship, the William Buchanan, was wrecked and burned to the waterline, and Jacobs was reported to be “much burnt.” Jacobs wrote a letter to the editor of the Sydney Herald to clear himself, the Captain and the crew “from imputations which, if true, ought to deprive us of our respective positions in the mercantile marine.” But he never went to sea again.

At the end of January, Mr and Mrs Jacobs returned to Hobart from Sydney. They moved in with Charlotte’s extended family in her mother’s house in Cross Street, Sandy Bay, where they had been living off and on since their marriage twelve years before. They didn’t have a home of their own. Perhaps it was because Jacobs had lost his savings paying off his crew when an owner shirked his duty in 1862. Perhaps it was because Charlotte so often went to sea with him, or perhaps it was simply because they chose to pool their resources with the family. For whatever reason, the Jacobses left the sea, and moved in with Charlotte’s mother Sisly Rowland and younger brother George (a shipwright). William eventually advertised as a navigation instructor on moderate terms.

And that takes us back to the logbook. Ten months after William and Charlotte returned to Hobart, scarred in perhaps more than one way by the sea, one of them pulled out the logbook that recorded their honeymoon voyage, and the ghost of the first Mrs Jacobs. Someone dusted it off, opened it up, and gave it to little five year old Esther to practice her writing and learn her lessons. But why was Esther living in her grandmother’s home, with her uncles and aunt? Where were her parents? That part of the story is coming up in the next installment, so please stay tuned!

Further Reading:

The State Library of Tasmania, together with the Tasmanian Archives, the Allport Library and Museum of Fine arts, and the Crowther Collection hold an absolute treasure trove of material on whaling, not just in the Southern Oceans, but around the world. Below are just a few of the highlights (you’ll find more than 1500 entries for “whaling” in the catalogue). If you are interested and would like further information or a longer bibliography, please put in a reference enquiry, we’ll get back to you with suggestions.

CRO82: Ships’ Logs, 1813 – 1931. This is one of the largest collections of whaling logbooks in the Southern Hemisphere, and it’s partly digitized. The Log of the Nimrod is in CRO82/1/3.

If you’re interested in whaling, then you should make the Allport Library and Museum of Fine Arts one of your first ports of call! There’s a fabulous collection of whaling artwork on display, some of which features in this blog.

While the wonderful Maritime Museum of Tasmania is currently closed, their collection database is online, and their team are responding to research inquiries. Visit them online here: http://www.maritimetas.org/

There are many more fascinating stories to be uncovered by looking at the crew manifests of whaling voyages (MB2/33: Official Agreements, Accounts and Logs for Masters and Crews Signed on at Hobart). We have many of these on microfilm, and you can have a look at them yourself in the Microspace at 91 Murray Street. If you can’t make it to Hobart, we can check a ship for you – just put in a research request for an hour of free research by one of our experienced staff.

Here are just a few of the books in our collection or available via interlibrary loan if you’re interested in colonial whaling and whaling families. This is just the tip of the iceberg, so please get in touch if you’d like other suggestions.

Susan Chamberlain, “The Hobart Whaling Industry, 1830-1900” PhD Thesis, LaTrobe University, 1988.

To hear the author talking to Joel Rheinberger on ABC Local Radio Tasmania (back in 2019 – at the beginning of this research!), check out the link here: https://www.abc.net.au/radio/hobart/programs/statewideweekends/the-story-of-esther/11577546

Hi Anna, I have just come across this! Esther is my great great grandmother. I wear a locket of hers that was given to her on the occasion of her christening. I will read the rest of the blogs, and hopefully get in touch with you.

Louise

Hi Anna

I’m coming to this a bit late having only just discovered & subscribed to the blog. Great stuff and thanks for all the juicy links to follow.

It immediately reminded me of another chance discovery of a story of little girls, their copy books & a maritime connection. I wonder if you have seen it?

https://www.batterypointhall.org.au/the-two-little-girls-in-our-attic/

Lisa

Lisa, what an absolutely astonishing connection! I had not seen the article, but this is truly incredible. Thank you ever so much for sharing!

Absolutely awesome story. I came across this on the ABC website and wondered if Esthers uncle William Jacobs was Williams Forbes Jacobs who was my 3rd great grandfathers brother. It is! Your investgations revealed a lot more than what I knew about William Forbes Jacobs however it is Esthers story that shines!. You have done a marvellous job taking dry historical facts and weaving them into a well fleshed-out story. I cant help but think that it would make a lovely ABC TV series. I can see a lot of home learning kids really connecting with Esther.

Hi Shay, I am so delighted that you liked it – especially as it featured a relative! Thank you so much for your very kind words, and I am just so pleased to have helped you fill in some pieces of your puzzle, and that the story connected with you so much. I would love to know more about the family connection – there was so much more, of course, that I wanted to weave into the story – William Forbes Jacobs and his first wife Amelia, how he went to sea, what he did before he went whaling, how he came out to Australia – some of which I was able to discover and some of which is still elusive. Would you mind if I sent you a message separately so I could follow up?

Anna, yes please contact me however I expect you have revealed far more than I know.

Hi Anna, I am not sure whether you have discovered this genealogy page, with a photo of

Esther Paul? The image is about half way down the page. I stumbled across this site when I googled Esther’s name. http://www.chestnut-blue.com/Chestnut%20Blue-o/g0/p836.htm?fbclid=IwAR0WkX8V3IrQFqemca5prNCqxBke8t5YFDwJP-h3g0iLn98AC1wY_Eafdkk

Hi Sandra – I have seen that website and the photograph of Esther! I was actually planning to link to it in the next installment of the blog – but you’ve anticipated me! I’m so glad you’ve gotten inspired and done some digging of your own – there is so much left to investigate in her story. The next chapter should be up soon!

Fascinating story. Thank you Anna. Impressive research, bringing Esther’s story and her family to life. When is the next instalment coming out? Kate Eagles

By the way when I try to post this, I get:

Warning: Use of undefined constant j – assumed ‘j’ (this will throw an Error in a future version of PHP) in /home/customer/www/archivesandheritageblog.libraries.tas.gov.au/public_html/wp-content/plugins/math-comment-spam-protection/math-comment-spam-protection.classes.php on line 70

Warning: Cannot modify header information – headers already sent by (output started at /home/customer/www/archivesandheritageblog.libraries.tas.gov.au/public_html/wp-content/plugins/math-comment-spam-protection/math-comment-spam-protection.classes.php:70) in /home/customer/www/archivesandheritageblog.libraries.tas.gov.au/public_html/wp-includes/comment.php on line 560

Hi Kate, I am so glad that you enjoyed it! New instalments of Esther’s Story are coming out each Friday, and I’ve just posted a new one We have to manually approve each of the comments, so perhaps that’s why you’re having those weird messages? Sorry about that!

Fascinating story. Thank you Anna. Impressive research, bringing Esther’s story and her family to life. When is the next instalment coming out?

Thanks so much, Kate, I really appreciate that! New instalment is out today!

Loved your talk today, Anna! And congratulations on your research, putting it all together. I can’t wait for the next instalment!

Kate Eagles

Thank you! I’m so glad you enjoyed it. It will also be posted on our YouTube channel, I think, so stay tuned (forgive the pun!).

Fascinating story!

I think so, too! So glad you enjoyed it.

Hi Anna. Thanks for this intriguing story! Where was Cross Street? The only one I can find near Sandy Bay is the street that is now McGregor St, Battery Point.

Hi Felicity, so glad you are enjoying it! I have been struggling and struggling to find Cross Street myself – I thought it was McGregor Street, too, but there’s other evidence to suggest it wasn’t. There’s a bit more about that in next week’s installment!

What a fascinating (and well documented) story. I’m looking forward to the next installment.

I am so glad you enjoyed it, Sally!