Colonial Cunning Folk, part two: Moses Jewitt and Benjamin Nokes

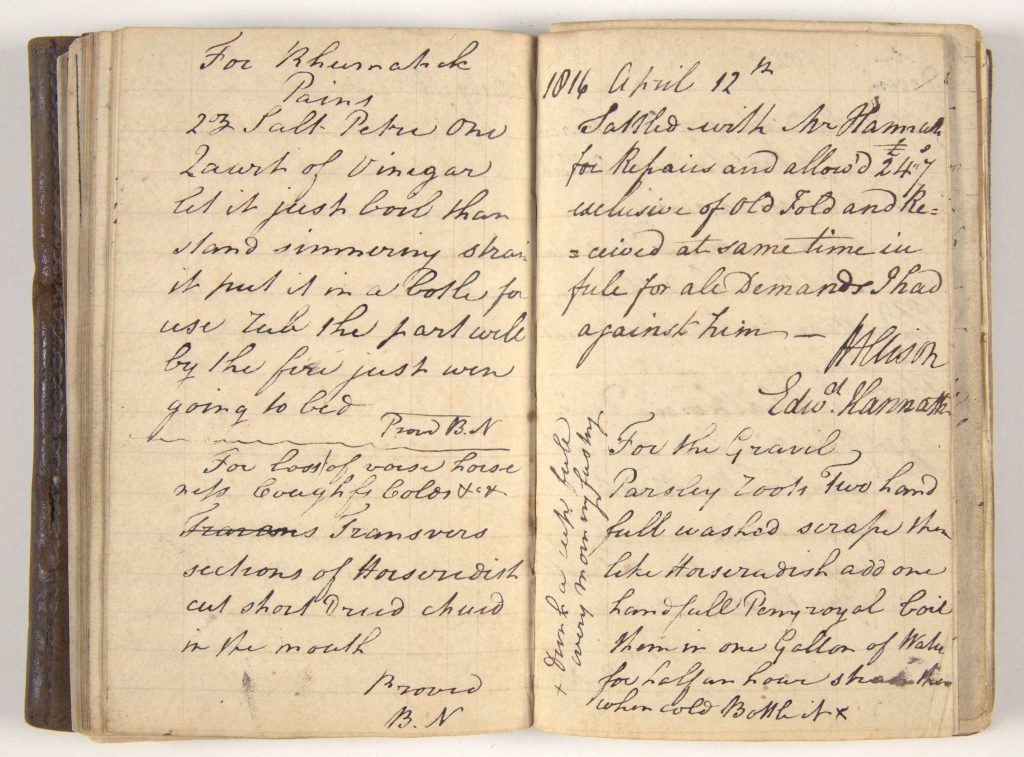

Our previous post described the notebook of William Allison, a cunning man or traditional healer active in Van Diemen’s Land during the 1830s and 1840s. Survivals of such documents are extremely rare, and unheard of in colonial Australia. Besides recording Allison’s activities, his notebook sheds light on his network, naming two other practitioners from whom he obtained recipes: Moses Jewell or Jewitt, and Benj Knokes also noted as ‘BN’.

One recipe, which appears to be for a ‘witch bottle’ (a protection against malign magic), is credited to Moses Jewell or Jewitt, of Durham. So far, nothing concrete has been established about him: he may be the publican Moses Jewitt mentioned in the Yorkshire Gazette 12 April 1828, but this identification is speculative. Allison was highly mobile, regularly travelling between Lancashire and Yorkshire, and it is reasonable to assume that other practitioners were too.

‘Dr Nokes’

The life of ‘Benj Knokes’, by contrast, is well-documented. Like Allison, he was widely known and respected in Van Diemen’s Land.

Benjamin Noke or Nokes (ca.1780?-1843) was raised in a ‘Dissenting’ family (R.D. Pretyman, Chronicle of Methodism in Van Diemen’s Land 1820-1840, Aldersgate, 1970, p.16). He was convicted at the Essex Assizes in 1809, of a burglary at the house of the Rev. T. Adams, Kelvedon (Bury and Norwich Post, 22 March 1809). Prison records give his age as 30. The initial death sentence was commuted to transportation for life.

Nokes arrived in Hobart in 1812, during the period of corrupt military rule following the death of Lieutenant-Governor David Collins (Alison Alexander, Corruption and skullduggery, Pillinger, 2014). In 1816 he was found guilty of receiving stolen goods, but apart from this he maintained a clean record. By 1822 he was sufficiently prosperous to marry 23-year old Sarah Wicks or Weeks. The marriage certificate records Nokes’s age as 35; however this record is clearly unreliable as it also records both parties as ‘free’: both were convicts. Sarah had been convicted of forgery, and like Benjamin was initially sentenced to death; she arrived in Hobart in May 1820.

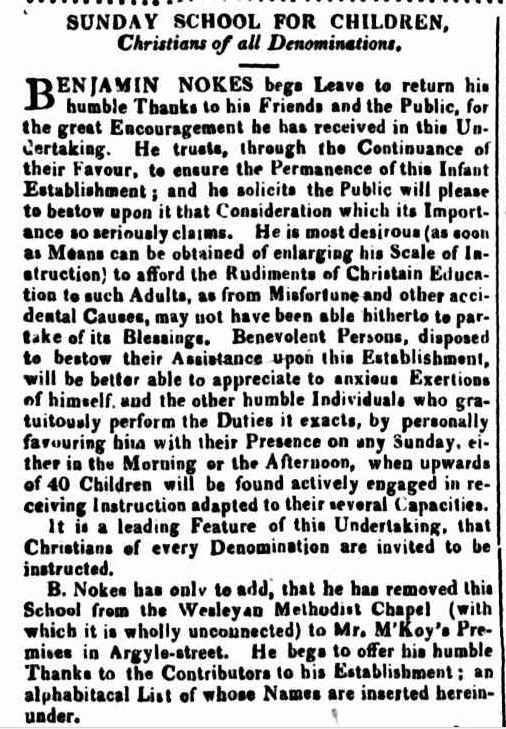

Nokes was one of the founders of Methodism in Van Diemen’s Land. In 1820-21, with Corporal George Waddy, he formed a congregation and established a Sunday School. The first Minister, William Horton, arrived in 1821 and conflict was almost immediate. Horton reported that Nokes ‘had not a very perfect knowledge of Methodism’ and that the school ‘exhibited some small deficiencies and irregularities’ – sufficient to justify Horton taking over teaching (Pretyman, p.30). Nokes left the congregation and attempted unsuccessfully to establish a rival school open to ‘Christians of all Denominations’ (Hobart Town Gazette, 22 June 1822, supplement p.1).

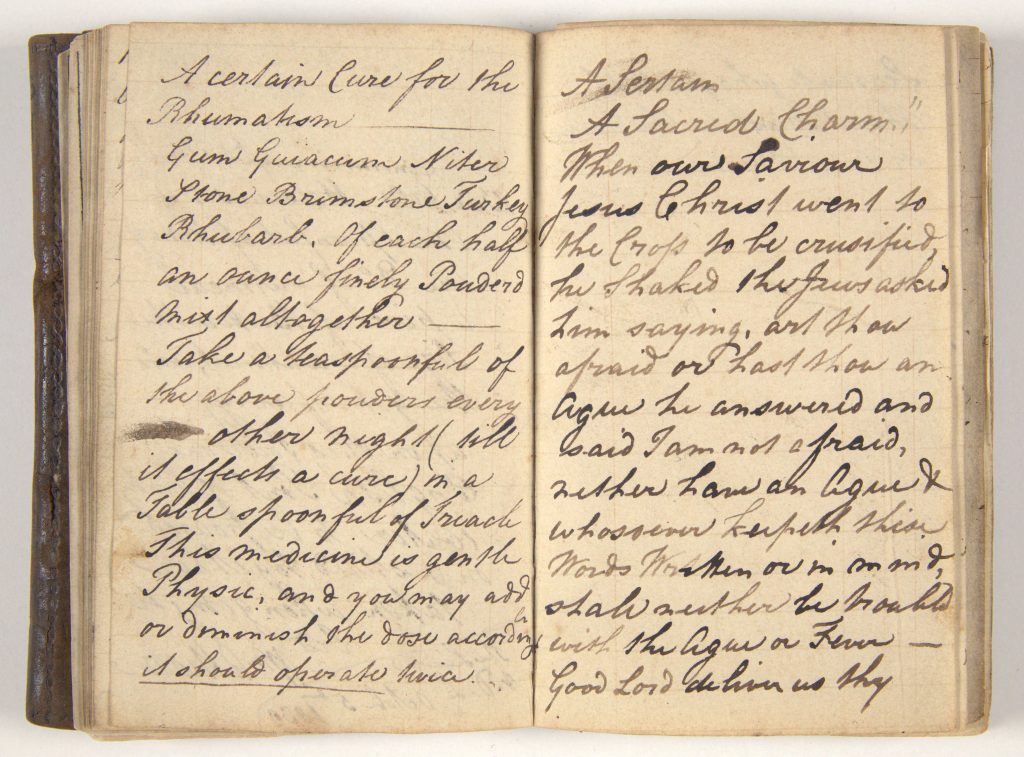

There is no inherent contradiction in a practitioner of folk magic also identifying as a Christian. Bibles and other religious texts have always been potent ritual objects in magical practice, as well as sources of names for incantations (Owen Davies, Grimoires: a history of magic books, OUP, 2009). William Allison’s notebook includes a ‘sacred charm’ with Christian elements. Whether such attitudes counted among Reverend Horton’s ‘irregularities’ we will probably never know.

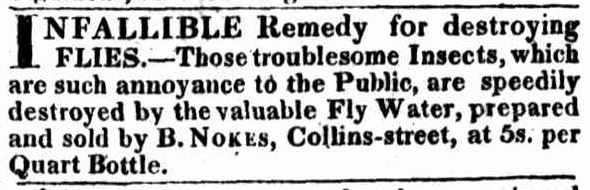

In 1823 Nokes received a grant of 200 acres near Brighton, and in the mid-1820s was running a shop in Hobart, at the bottom end of Collins Street, selling a range of goods including his own insect repellent (Hobart Town Gazette, 20 December 1823, p.2). Andrew Bent’s 1825 almanac lists him as a ‘dealer and botanist’ in Collins Street.

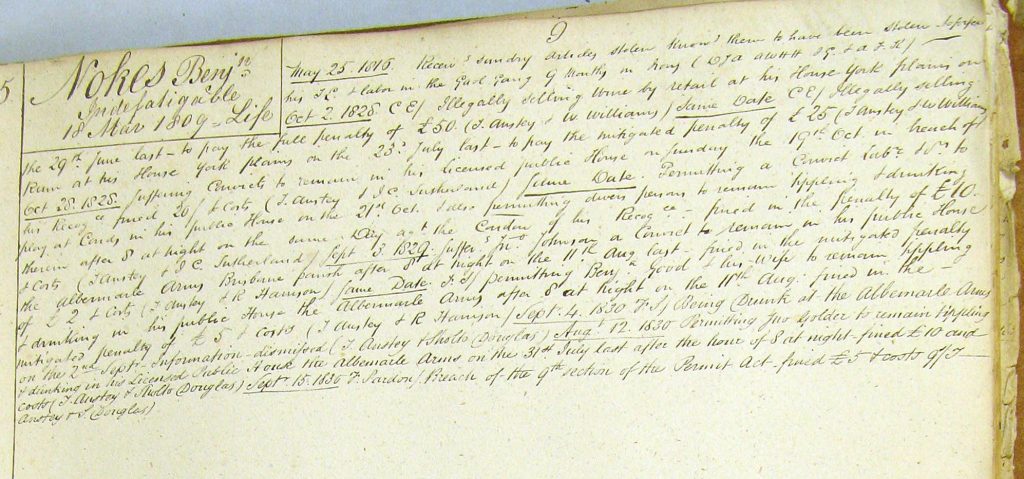

Around June 1828 he took over the licence of the Albemarle Arms at York Plains, then on the main road between Hobart and Launceston. It was a notoriously rough place (Hobart Town Courier 1 Nov 1828, p.2), and the local magistrates took an active interest. Nokes was prosecuted nine times in his two years as licensee.

Sarah died in August 1828, after a long illness ‘which she bore with Christian fortitude’ (Hobart Town Courier, 6 Sept 1828, p.2). This personal tragedy undoubtedly impacted Benjamin’s ability to keep order in a rough pub. Curiously, his last conviction, in September 1830, was recorded on the same date as his pardon. He gave up inn-keeping at that point, and the York Plains licence was transferred to Joseph Howell.

The Southern Midlands at this time was the epicentre of conflict between Aboriginal people and white farmers. In July 1830 the Launceston Advertiser and the Hobart Town Courier both reported a dramatic encounter between Nokes and a group of Aboriginal warriors. The drama swiftly turned to ridicule: the Colonial Times (23 July 1830, p.3) published a revised report, stating drily that the military party sent to investigate found only a circle of blackened tree stumps.

Around May 1832 Nokes was at McGill’s Marshes, where he met William Allison. In August 1832 he had a legal dispute with Francis Fleming, Blackman’s River, near Ross, involving a farm lease (Hobart Town Courier, 7 February 1832, p.1).

By 1834 he was at Bagdad, and – extremely unusually for a rural cunning man – advertising in the press. The Colonist (18 March 1834, p.2), reported his success in curing ‘the gravel’ (kidney stones). William Allison’s notebook includes a remedy ‘for the gravel’, but it is unattributed.

Benjamin Nokes died of a stroke in Hobart on 19 September 1843. The official record of his death gives his age as 72 and his occupation as ‘Doctor’. If his marriage and gaol records are correct, he was probably closer to 60; but as with Allison the critical point is that his activities as a healer were sufficiently well-known to be officially recorded.

Benjamin Nokes’s recipes can be read in William Allison’s notebook.

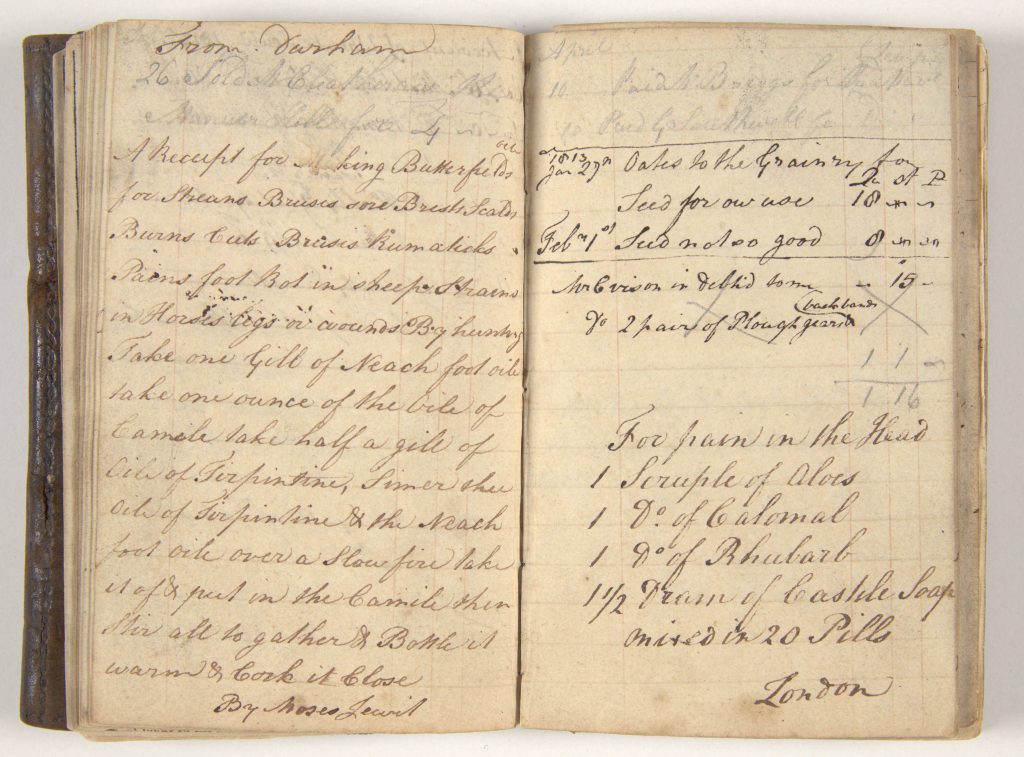

The Moses Jewit recipe is not for a witch bottle – or remotely magical. It’s for ‘Butterfield’s Oil’ (or a homemade version of it), a popular liniment made by Stephen Butterfield, a horse breaker from Darlington, a town in County Durham, who died in 1827. The recipe reads:

‘A Receipt for making Butterfield’s Oil for Streans [strains] Bruses Sore Brests Scabs Burns Cuts Bruses Rumaticks Pains foot Rot in Sheep Stains in Horses legs or Wounds by hunting.

Take one Gill of Neach foot oile [neatsfoot oil – traditionally made from the shinbones and feet, but not the hooves, of cows] take one ounce of the Oile of Camile [oil of chamomile, made by steeping chamomile flowers in oil]

Take half a gill of Oile of Tirpentine, Simer the oile of Tirpintine & the Neach foot oile over a slow fire. Take it of & put in the Camile then Stir all to gather [together] & Bottle it warm & Cork it Close. By Moses Jewit.

Thank you, Sarah for your comment and clarification! I doubt that any witches would be enticed into a bottle containing that particularly bracing liniment, though it might work well as a repellent…

Your work here is impressive. Have you done it with any of the other remedies in the almanac?

This is a really excellent piece of research work by Ian Morrison. Two important but little-known men in the history of Tasmania have been identified and brought out of the background into which they had faded. Thank you, Ian Morrison, for a fascinating story, well told.