91 Stories: Cabinet of Curiosities

Natural history collections are not only useful to scientists. They also reflect the life of the collector, his or her family, their connections, and the worlds they inhabited – even the state of their digestion! Ruth Mollison’s story about Morton Allport’s shell collection is a piece of detective work, a personal history, and an insightful (and sometimes unnerving) exploration of how one Tasmanian family intertwined art, science, reputation and obsession.

Shells, Families, Histories

I have a life long interest in natural history, and worked in the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery invertebrate collection for several years. The job I enjoyed most was sorting the shell collection, including preparing a shell cabinet for display in the zoology gallery. While investigating the drawers of carefully labelled shells from Tasmanian beaches, I discovered many shells that my father had collected. It reminded me of evenings as a child at the dining table watching Dad prepare his shells – I was given the job of winding cotton around bivalves to hold the parts together. It was a job for nimble fingers. My father’s shell cabinet was eventually donated to the Museum, and these were the shells I came across while working there.

As I was reading Dad’s handwritten labels stating the location and date where the shells were collected, I realized that I could trace my father’s movements and location for several years in the 1960s, across Tasmania. He had often been walking along a remote beach at significant times in my large family’s domestic life – a distant father in many ways!

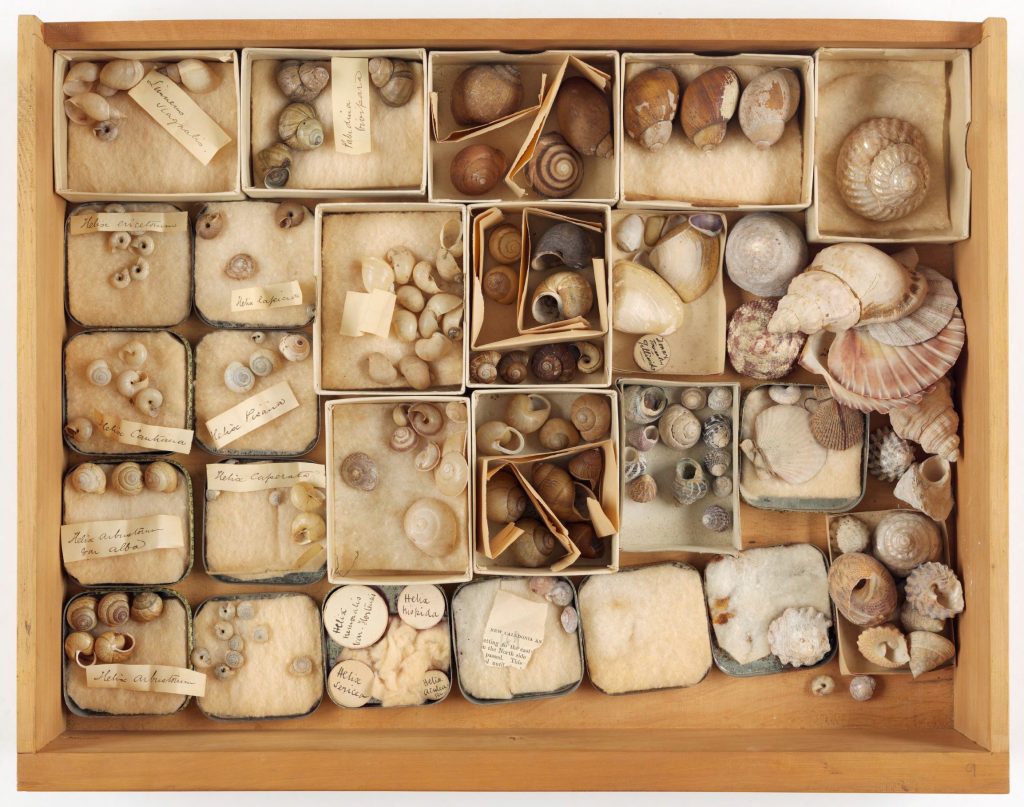

In my next position as curator of the Allport Library and Museum of Fine Arts, I was excited to discover, lurking on the 11th floor of the Library building, a Huon Pine cabinet shrouded in white dust sheets. In the library catalogue it is described as a “fitted cabinet holding Morton Allport’s collection of shells with 2 lockable panelled wood doors enclosing a set of 24 drawers.” It was formerly in the cellar at Cedar Court, Henry Allport’s house in Sandy Bay.

It took a year or so until I could find the time to muster the necessary resources to properly investigate this cabinet. Because of its age and delicacy, an objects conservator (Michelle Berry) was contracted to assess the contents. Also, an expert in Tasmanian land snails (Dr Kevin Bonham) cast an eye over the contents. First of all, each drawer was carefully carried down to the basement to be photographed. I waited in anticipation for Dr Bonham’s report as the contents could be of great scientific interest – containing shells collected from Tasmania in the 1860s, one hundred years prior to my father’s collection.

“I shall never open your drawers without fear of snakes and creeping things.”

Morton Allport arrived in Tasmania (then Van Diemen’s Land) in 1831 as an infant with his parents Joseph and Mary Allport, both free settlers. His mother was a talented artist and curious about the natural history of her adopted country. She passed this curiosity onto her son, but remarked after he left home: “ I shall never open your drawers without fear of snakes and creeping things.”

As a young man, Morton was interested in the natural history of Tasmania – he dabbled in taxidermy, fossicked for gemstones and fossils, pinned insects and collected bird’s eggs and shells. After completing his school education, he was articled to his father’s law firm, Allport and Roberts.

“I wish you could see my cabinets I should astonish you”

I was hoping the cabinet would be a treasure trove of local shells, perhaps an artefact of an early scientific survey of Tasmanian shells. However, it didn’t take long to realize that it was not a collection of a scientist, but rather that of a shell collector. The essential data that always goes with a natural history collection, date and location, were missing.

Morton was particularly interested in land snails and freshwater snails. He collected land snails from around Australia, writing to his cousin, “I wish you could see my cabinets I should astonish you upwards of 500 sp. land shells principally Australian and some of these enormous, three inches across- takes about 2 cabbages a day to feed them I should think.” To a Dr Cox in Sydney he wrote, “I am collecting for you as fast as I can and will send a box jointly with the Royal Society as soon as we have a respectable number of specimens.”

Morton was an active and enthusiastic member of acclimatization societies. These were colonial societies established by well-off gentlemen to encourage the introduction and exchange of plants and animals from England, Europe and the colonies.

It suited Morton’s interests and ambitions to set up a trade in introduced animals and plants. His specialty were the seeds of the white water lily, and fry of redfin perch and tench. He enthusiastically distributed these to friends and acclimatization societies all around Australia and New Zealand.

He also introduced a freshwater snail. These were most likely transported from England by his brother Curzon in 1862, in an aquarium he kept in his cabin along with other of freshwater species. The freshwater snails were bred and released to provide food for the introduced tench and trout.

Chocolate, Golf, and Indigestion: Hidden Histories of Upcycled Containers

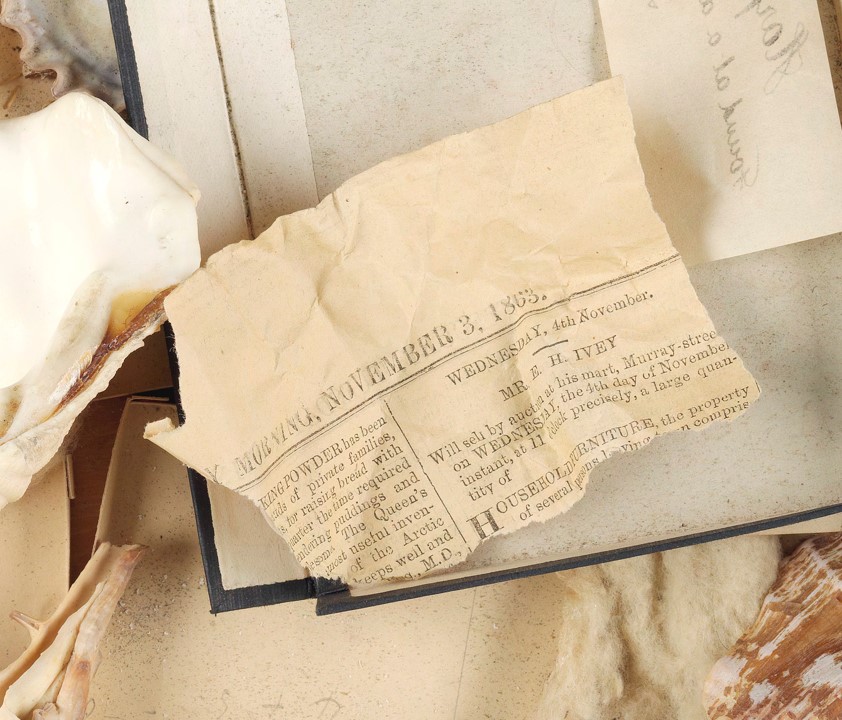

Because of the lack of labelling, I felt the need to verify the age of the contents of the cabinet. A scrap of old newspaper fortunately had a date of 1863 which gave me confidence that the contents were from this era. I also looked at the specimen boxes to see if they provided a time of collection.

There are at least 50 Capstan navy cut cigarette boxes and tins in the drawers, just the right size for housing large shells. Capstan cigarettes were launched by W.D. & H.O. Wills in 1894, and were a popular brand of cigarettes in the early 20th century. Morton Allport died in 1878 so he would have most likely have smoked a pipe rather than cigarettes. Therefore the next generation of Allports after Morton – either his son Cecil Allport (1858 – 1926) or grandsons Henry Allport (1890 – 1965) and Morton –the- younger Allport (1887-1916) must have re- arranged the shells at some time, using the cigarette boxes.

A clue to which Allport came from a faded handwritten golf club petty cash label stuck on one of the tins. Morton –the- younger and his younger brother Henry Allport were both keen golfers and as Morton –the- younger died in World War 1, it is most likely to be Henry that re-housed many of the shells.

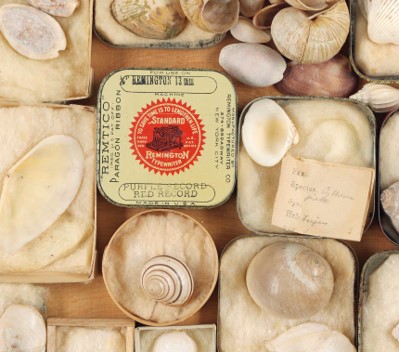

Another clue to the age and order of the cabinet are the various typewriter ribbon tins housing the small shells. The first year of production for The Remington typewriter was 1878, with spare ribbons sold in tins in the 1880s.

Morton’s son Cecil, also a lawyer, may have bought these home from his legal practice, or his son Henry, may have used these when typing up the many articles he wrote on Tasmanian art history.

Another upcycled container was for a Prices Patent Candle Company night light. Price’s Patent Candles Ltd. began manufacturing candles in 1830. By the end of the century the company was the largest maker of candles in the world. It made inexpensive stearine candles that burned almost as well as expensive beeswax candles. Candles made from this burned brightly without smoke or smell and were preferred as night lights.

Crunch-Foam Old Gold Chocolate was popular in the era of Morton’s children/grandchildren. MacRobertson Steam Confectionery Works was founded in 1880 by Macpherson Robertson and operated by his family in Fitzroy, Melbourne until 1967 when it was sold to Cadbury.

Some of the occupants of the Allport household may have suffered from digestion problems, as evidenced from shell containers made from Seidlitz powder boxes and antibilious pills. Seidlitz powders were a digestion and laxative regulator containing tartaric acid, potassium sodium tartrate and sodium bicarbonate. It was manufactured from the mid-19th century onwards. The drink was described as “a cooling, agreeable draft”. Another item in the Allport household medicine chest was James Cockle’s antibilious pills. These antibilous pills are manufactured in London in the mid-nineteenth century.

Many Hands Make Light Work: The Allport Women and the Shell Cabinet

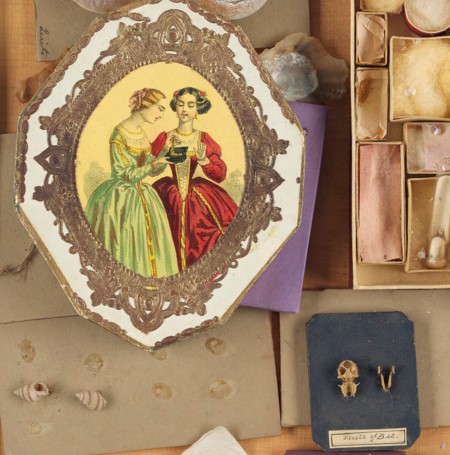

The women of the Allport household – who were also keenly interested in natural history – saved empty sewing thread boxes for re-use in the shell cabinet. A fine fabric camisole, mended many times and discarded as a rag was used to wrap up the claw of a giant deep sea crab in drawer no 24.

The very small shells and crustaceans are housed in handmade boxes. These are carefully folded out of re-purposed card, with the original print on the inside. Some have Mr Morton Allport printed neatly on the bottom, others are advertisements for Charles Wix and Sons, Manufacturers of pickles, sauces, and preserves.

The recycled card boxes give an insight into Morton’s correspondents.

One box has Mr Morton Allport C/- F.J.Prout Esqu, London. This is most likely one of the artist’s John Skinner Prout’s children, Francis John Prout born in Hobart in 1845.

John Skinner Prout and his family had lived in Tasmania for some time before moving back to England, and the Allports were family friends. In his twenties, Morton spent a year on the Grand Tour of England and Europe, as part of a young gentleman’s education. Unusually, for someone whose life is so well documented, there is little information of where he stayed in England, so this fills in a little of that puzzle.

Perhaps these boxes were carefully folded by Morton’s young daughter Curzona Frances Louise Allport (aka Lily).

Other items in the drawers bear witness to Morton’s varied interests. There are glass eyes for taxidermy, egg blowers (TMAG has Morton’s native bird egg collection), a bat’s skull and a dried tortoise. Like many family heirlooms, the cabinet has evidence of several generations of Allports contributing to its contents.

Ambition and Grave Robbing: The Dark Side of Morton Allport’s Collections

Morton Allport spent a lot of time, energy and money sending natural history collections to institutions overseas. These included thylacine skins, insects, and molluscs. In exchange he was granted membership of many respected scientific institutions in Europe.

As he matured into middle age, his quest for prestige motivated him to trade in human body parts. He paid Robert Gardiner, a landlord in Bass Strait, also known as ‘resurrection Bob’ to exhume Tasmanian Aboriginal graves on Flinders Island. He sent many skeletons to anthropologists in England and Europe, but he managed to avoid the public notoriety of Dr William Crowther.

During the recent exhibition The Lanney Pillar, Morton Allport’s letterbooks were digitized and placed on display in the Allport gallery, publicly documenting how he linked his reputation to the traffic in human remains and myth of Tasmanian Aboriginal extinction.

The (After)Lives of Shells and Cabinets

After Morton died, his son Cecil intended to give the shell cabinet to his oldest son Morton the younger, but he died in WWI, so it passed onto his younger son Henry. When Henry died in 1965, he bequeathed his house Cedar Court in Sandy Bay and its contents to the Tasmanian Government to establish a museum and library. The shell cabinet was in the cellar. The house was eventually sold and the contents moved to a purpose built section of the State Library. The cabinet has been in storage since 1972.

Just recently I attended a very interesting talk by Dean Greeno about his research into the ecology of maireener shells used for making Tasmanian Aboriginal shell necklaces.

I was really pleased to alert him (via the Allport curator) to the presence of a very old box of maireener shells in the cabinet.

Dean was delighted to find they hadn’t been prepared properly before storing, as they still contained the dried animal – so they could be used to extract DNA.

It is ironic that Morton’s poor collecting technique has been useful to the present day Tasmanian Aboriginal community, by contributing to research on the decline of the culturally important maireener shells.

My initial assumptions on the importance of the shell cabinet as an early scientific survey of shells in Tasmania proved wrong. But then again, the shell cabinet proved to have other stories and other uses. As so often is the case with archival material, you cannot predict what questions may be asked in the future!

Congratulations on your excellent sleuthing. Ruth!

Even though the collection did not lead you to the scientific discovery you initially hoped for, you continued your investigation down those less travelled paths and uncovered some surprises!

What a most interesting story. Thankyou Ruth and others involved in bringing these objects and stories to light.

It was an intriguing project , glad you enjoyed it Alison .