Esther’s Story, Part Two: Getting By in Hobart, 1860-1870

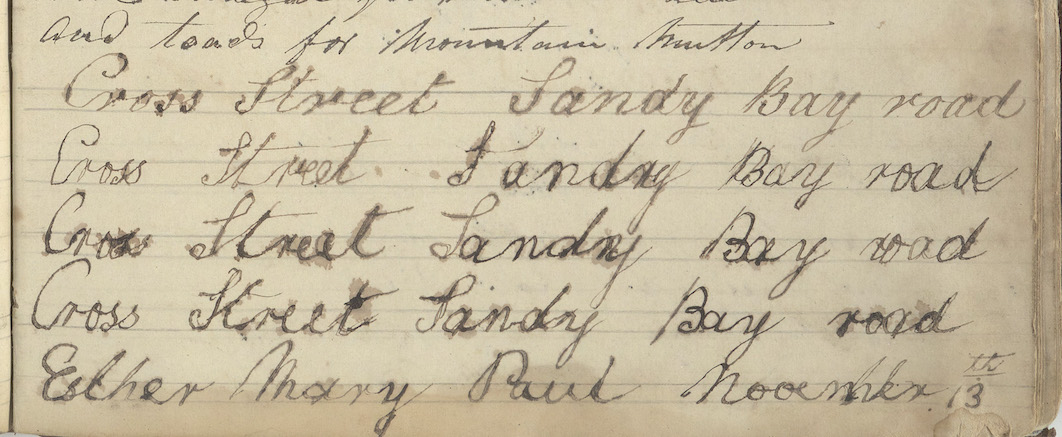

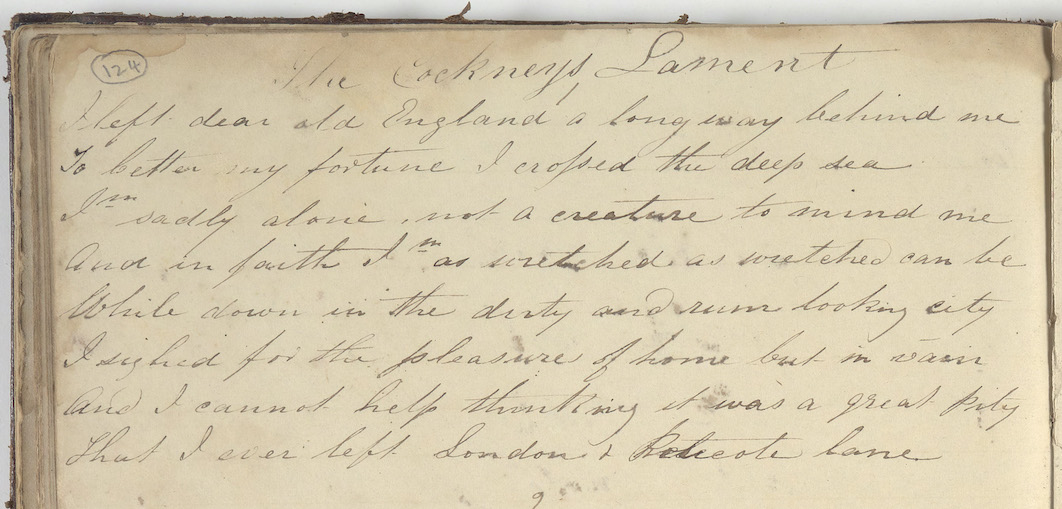

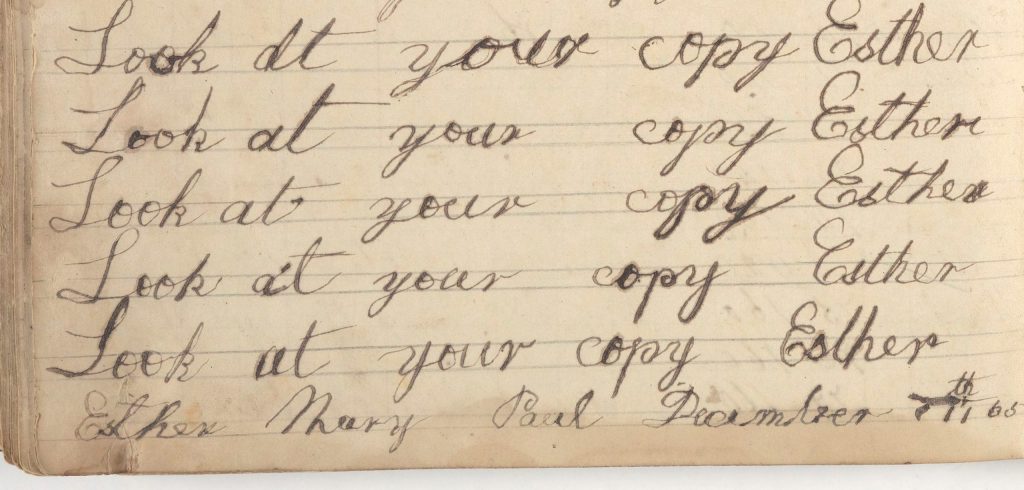

“Cross Street, Sandy Bay Road,” “Be a good girl, Esther,” “Esther shall not go out again,” “Bombay is in Asia, ABC,” “Evil communication corrupts,” “Love your grandmother Esther” – each of these were written over and over again in a whaler’s logbook, and signed “Esther Mary Paul” in November or December, 1865. What was little Esther doing writing these lines, in -between and alongside the records of her uncle and aunt’s adventures at sea long before she was born? Was she being educated or punished, or both? Where was she living and why was she there? In this continuing story of little Esther Mary Paul and the whaling logbook in the Crowther Collection, we’ll try to piece together Esther’s young life. It’s a tale of sorrow, struggle, and abandonment, but also of strength, resilience, and love.

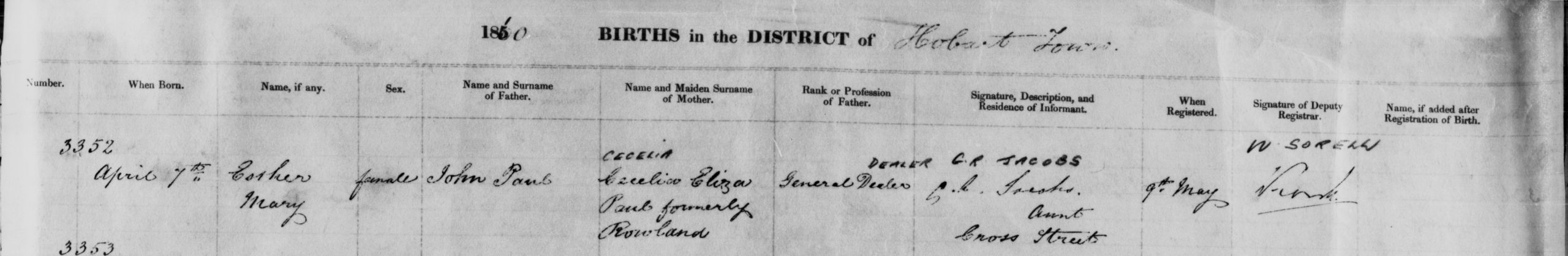

Esther Mary Paul was born in Hobart on the 7th of April, 1860, to Cecelia Eliza Rowland and John Paul. Her aunt Charlotte registered the baby’s birth – C. R. Jacobs, of “Cross Street.” It was this very address that, five and a half years later, little Esther would copy over and over in Captain William Forbes Jacobs’ old logbook.

Esther’s parents, John Paul and Cecilia Eliza (sometimes known as Ellen) Rowland, had married soon after the Rowland family arrived in Hobart in 1842. Cecilia was then 22, her younger sister Charlotte was 14, and her little brother George was 11. Over the next twenty years, as her little sister Charlotte grew up, married and went to sea (see last week’s chapter!), Cecilia had at least seven children, but possibly as many as eleven. Only two survived. When Esther was born in 1860, the family were living in Argyle Street, where her father was a general dealer, one of at least half a dozen occupations he had held, including corn-dealer and cow-keeper.

The family were not destitute, but their lives were still precarious. Tasmania was in the grip of a long economic depression in the 1860s. The number of shopkeepers like John Paul declined by up to 30%, prices fell, and according to W.A. Townsley, “The general picture… is of a colony over which hangs a seemingly perpetual depression, where standards of living are sinking and where pauperism and destitution are not uncommon…. If unforeseen misfortune struck, the results were generally quite tragic.” (Townsley, 1955).

Moreover, the life of a “general dealer” was always uncertain, and sometimes dangerous. There were plenty of general dealers around Argyle Street and Brisbane Street, both men and women, selling a wide assortment of second hand goods. They turned up in the newspapers fairly often, usually because they’d received stolen goods (everything from paper-mache tables to trousers to bacon!). They were also always at risk of being robbed themselves. Some dealers employed hawkers to take their goods and sell them around the country districts, which meant that they were also at risk of being defrauded.

Then there were the threats of violence. When Esther was 2 years old, a neighbour, Thomas Bennet, reported that a man barged into his shop, pulled his coat off, and declared, “I will thrash you and knock your brains out, when I catch you.” There were plenty of other similar accounts in the newspapers, mostly springing from debts. The Paul family seem to have escaped robbery, receipt of stolen goods, and violence – but not misfortune.

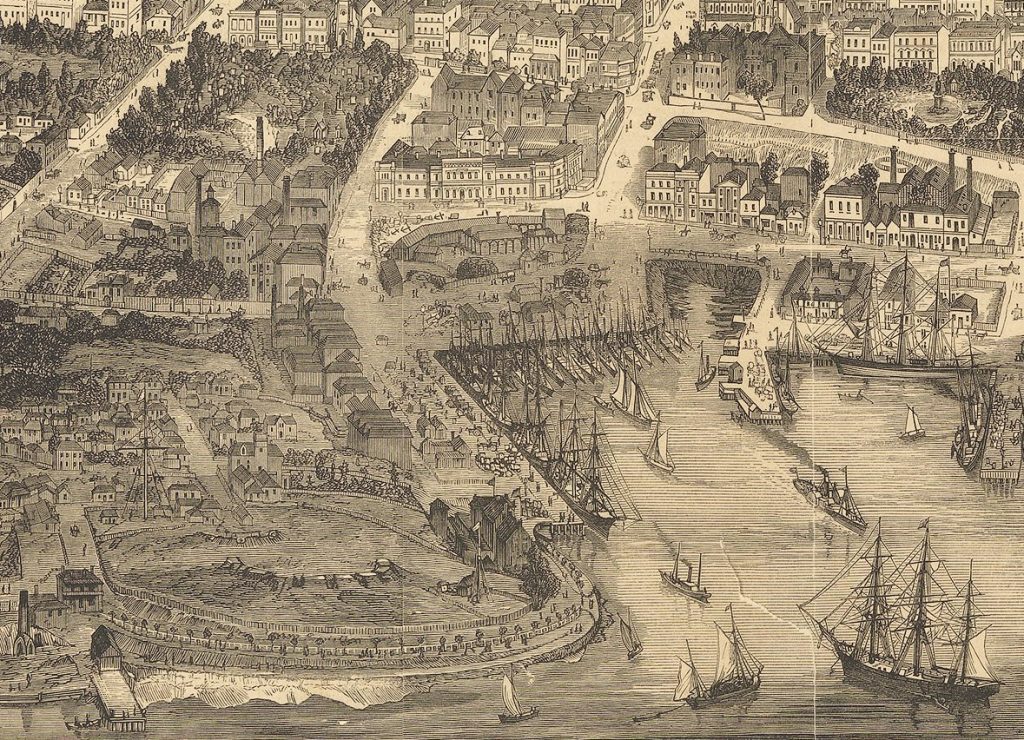

Around the time of Esther’s birth, the family seems to have suffered a series of personal and financial hardships. Saddest of all were the losses of their children, many of whom were named after Charlotte and William Forbes Jacobs. As this 1898 map shows, the area where Esther was born were still hot spots of infant mortality, dysentery, typhoid fever and scarlet fever until the end of the century. The year before Esther was born, her parents lost their one-year old daughter Charlotte to dysentery. Then came the flu epidemic of 1860 (Esther was born in its aftermath). In 1862 the household was struck by dysentery again, killing her newborn baby brother William. Esther’s mother Cecilia went to have twins in 1863, but they were born prematurely, first Edward Forbes Paul at 6 weeks, and then Sarah died at 7 weeks .

Around this time, Esther’s father left. His business fortunes had plunged, and following the trail of occupations on his children’s birth and death certificates, you can see him go from a general dealer in 1860 to a corn dealer in 1861 to a cow keeper in 1863. Esther’s parents told different stories about what happened. John Paul claimed that he was disabled and lost the use of his leg, and was forced to go hawking about the country near New Norfolk, and when he returned to Argyle Street, “I found my home broken up, my wife and family gone, taking with them all my furniture and effects to the value of £70.” Cecilia would tell a different story – that John Paul had left her and her surviving children destitute, that he had ‘ruined and almost starved his wife and two children” and she would have nothing more to do with him. We’ll get to that part of the story in next week’s instalment of Esther’s Story.

Two things seem clear to me. The first is that the period between 1863 and 1865 seems to have been a breaking point for the Paul family. Their health wasn’t good – from the frequent bouts of dysentery that had taken their little children, to Cecelia’s near-constant pregnancies for twenty years, to John’s crippling rheumatism. They were technically middle-class, but their economic situation was extremely fragile. Then sometime around 1863 or 1864, John left the grieving family without means of support.

The second thing that I noticed is that Cecelia seems to have been very close to her younger sister Charlotte and Charlotte’s sea captain husband, William Forbes Jacobs. Both of them turn up as informants on the children’s birth records, and some of the children were their namesakes. At one point, Cecelia was even claiming that her maiden name was Jacobs, not Rowland. So perhaps it is not so surprising that we find Esther writing in Captain Jacobs’s logbook in November of 1865.

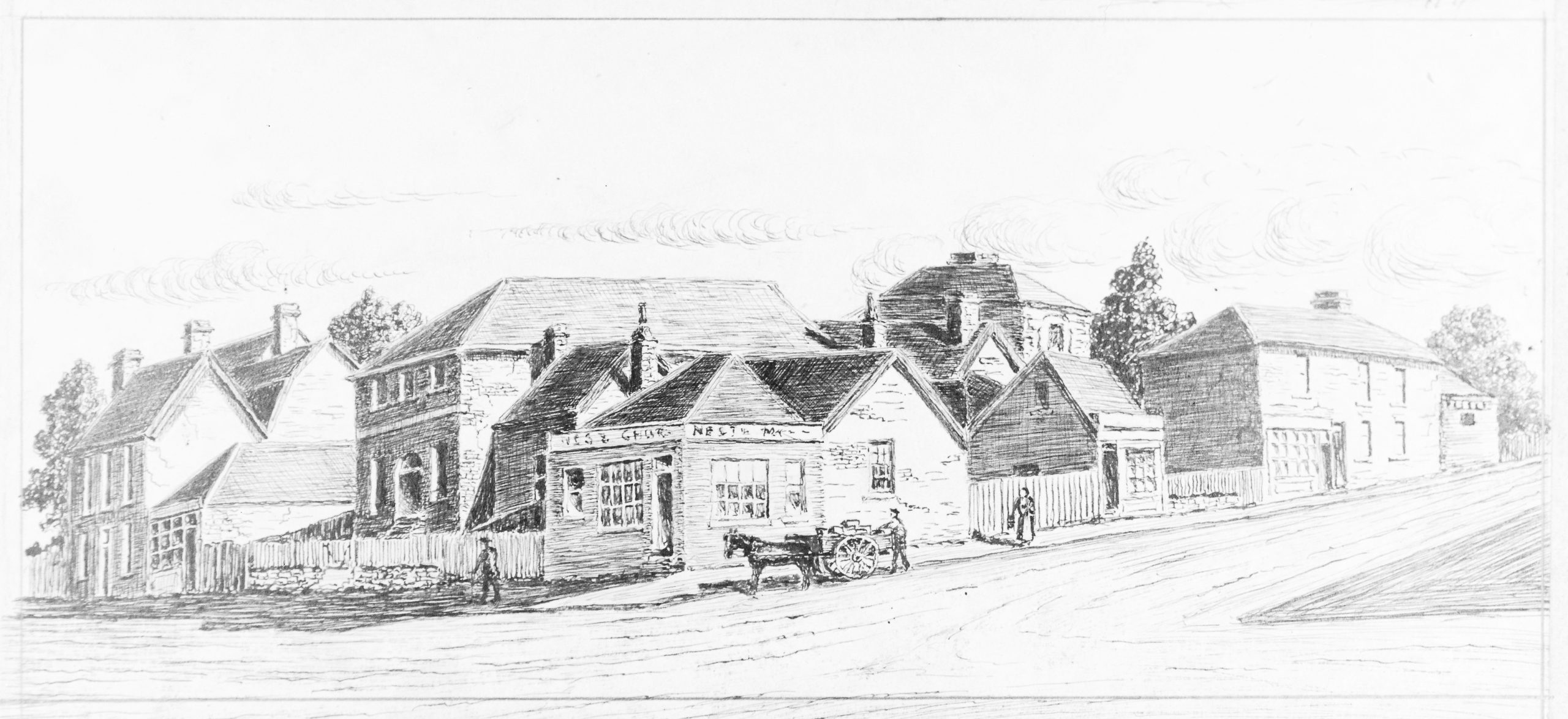

Cross Street, Sandy Bay Road

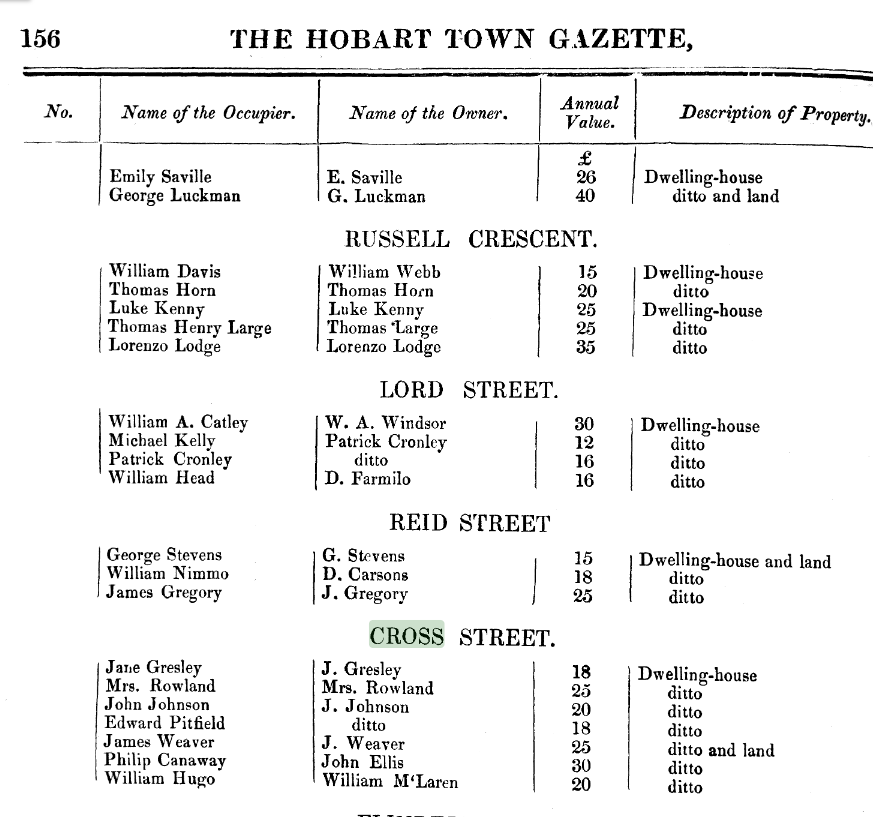

We can’t know for certain when Esther arrived at Cross Street, Sandy Bay Road, whether she came alone, or whether her mother was with her. We also can’t be certain as to why she moved into the house, though I think the circumstantial evidence is compelling for a terrible financial and emotional upset in the midst of a prolonged economic depression. What we do know, from the valuation rolls, is that they were not alone. Little Esther (and perhaps her mother) moved in with their extended family: her widowed grandmother Cecily (or Sisly) Rowland, her uncle George Rowland, and her itinerant uncle and aunt William and Charlotte Jacobs.

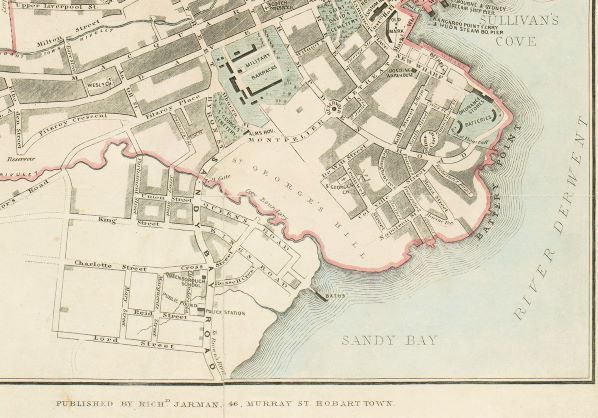

For a long time, I had an image in my mind of little Esther scribbling away in the logbook in a house owned by the Jacobs family in Cross Street, Battery Point (now McGregor Street), surrounded by scrimshaw and artifacts from her uncle and aunt’s voyages, and with other seafaring families on all sides. The Rowland family owned a house in Kelly Street, after all, and that was just around the corner, and there were plenty of other whaling captains and their families in the area. But I think now, as romantic as that image is, I was dead wrong.

Esther wrote her address correctly. She was living with her grandmother, Cecily Rowland, who owned a house in Cross Street, and which is always identified in the valuation rolls as near Sandy Bay Road. I struggled and struggled to find it, to no avail. Update: An eagle-eyed (and very dedicated) reader has found Cross Street on the Jarman 1858 map! Here it is!

Map of Hobart Town drawn & engraved by R. Jarman, c. 1858. This version shows the two Cross Streets that were confusing me! One is in Battery Point leading to Kelly St – but the other crosses Sandy Bay Road (Charlotte Street turns into it) until it joins Queen St. With many, many, many thanks to Felicity Hickman for her excellent research skills!

The Rowland house eventually ended up in the possession of Cecily’s son, George Rowland, a shipwright. This explains one passage in the logbook that had puzzled me before.

The Jacobs family were there too, having lived off and on at Cross Street whenever they were on land together. They had their own troubles. In 1862, Captain Jacobs was brought to court for having not paid his crew from the brig Union. He didn’t go whaling again, but made regular runs back and forth to the mainland, sometimes taking Charlotte with him. At exactly the time that the Paul family were in trouble in 1863, Charlotte and William Jacobs were sailing back and forth in the “fast sailing clipper Gratia” to Adelaide, Sydney, and Newcastle.

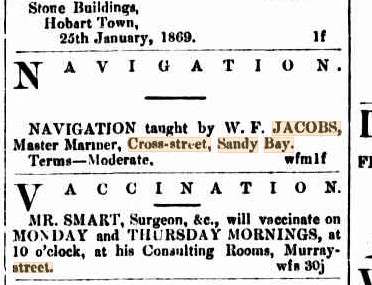

In 1864, tragedy ended William and Charlotte’s seafaring days. William Forbes Jacobs was the chief officer of the William Buchanan, which was running out of Sydney, and burnt to the waterline in December 1864. She ran aground, on fire, and the accounts at the time said that the captain and first mate had been “severely burnt” in the flames. William Jacobs never went to sea again. He and Charlotte returned to Hobart in early 1865, and moved back in with Charlotte’s mother, Cecily Rowland. Later that year, little Esther was writing in Captain Jacobs’s logbook. By January 1869, they were still at Cross Street, where Captain Jacobs was advertising as an instructor of navigation, at reasonable terms.

Educating Esther

So now we find ourselves at a place familiar to many of us these days – unexpectedly finding yourself in charge of a young child’s education. The only record we have of how the Rowland and Jacobs family managed this challenge comes from the logbook. We can’t know for certain that it was Aunt Charlotte setting the agenda and copying out the passages for Esther to learn. It could have been Esther’s uncle William, but it was unlikely to be her grandmother, who was illiterate (as you can tell from the birth record of one of Esther’s siblings – her grandmother signed her name with a cross). And the handwriting doesn’t seem to match that of Cecelia Eliza Paul (as I discovered today! But you’ll have to wait for next week’s instalment to find out yourself).

From the only record that we have, it seems that Esther’s education most closely resembled that she would have received as an older child. There weren’t yet any free Kindergartens for five year olds in Tasmania (see my colleague Leanne’s blog on this!). Education wouldn’t be compulsory until 1868, when Esther was 8. But at age 5, Esther was being taught at home, and from what I can tell, she was a pretty bright little thing.

The only evidence of Esther’s education comes from the logbook, but even that tells us quite a lot. Someone, perhaps Aunt Charlotte, copied out long passages for Esther to either read, or memorize, or both. A lot of this material looks like it might have been copied from ballads or broadsheets. They included Irish ballads about the pain of emigration (“Goodbye Mick” copied out in part on page 121) followed by a limerick about friars with a distinctly disrespectful tone. There was the Cockney’s Lament, another ballad about a homesick emigrant (“I’m sadly alone, not a creature to mind me/And in faith I’m as wretched as wretched can be”).

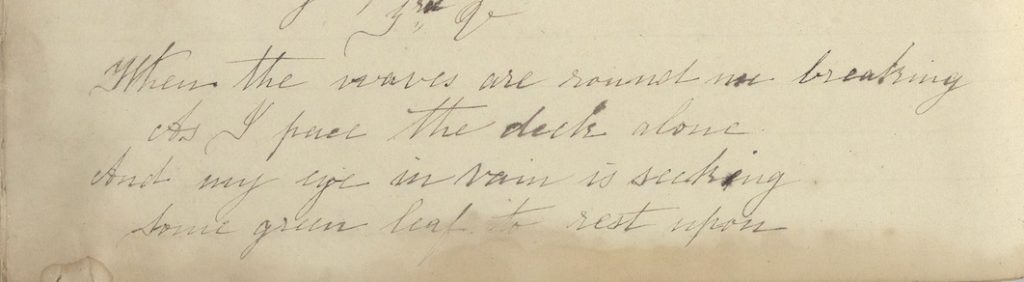

There are a few ballads about seafaring families, taken apart by the repeated comings and goings of ships and sea. “Goodbye, Sweetheart” is a sentimental poem about parting, but “Isle of Beauty, Fare Thee Well” is all about a captain leaving his home behind, as he paces the deck and wishes his wife, children, and friends well. Then there’s the “Ballad of Little Nell” a street ballad which appeared around 1849 in the UK, inspired by the character of Little Nell in Charles Dickens’ novel The Old Curiosity Shop. We have quite a good collection of ballads, by the way, and it would be a mighty interesting research project to delve into them.

As you might expect, many of these street ballads and limericks were pretty borderline in terms of what we’d think is acceptable for a five year old , not least because so many of them were viciously anti-Catholic. This was standard fare for Hobart in the 1860s, however, which was riven by sectarian tension. For example, the limerick on page 122 starts out, “What an illegant (sic) life a friar leads/ With a fat round paunch before him/He mutters a Prayer and counts his beads/And all the Woman (sic) adore him.” I found the original, by the bye, in an 1841 memoir entitled “Charles O’Malley: The Irish Dragoon.” You can check it out yourself if you’re a Libraries Tasmania member, and you’ll find it on p 379 – 380.

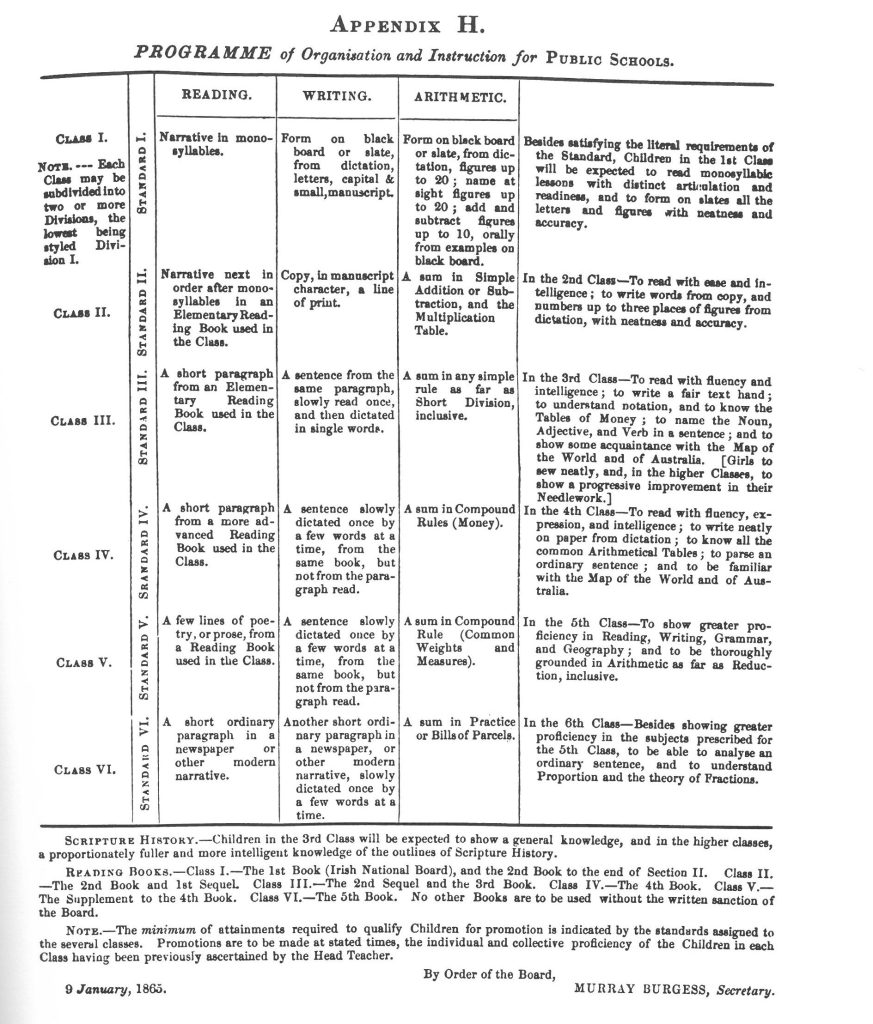

Now of course, standards change over time, and we can’t know whether Esther was actually reading the lines and lines of script written out for her, or if she was memorizing them. But she was copying out fairly long passages in script and practising her letters, at least one page every day. Based on what was expected of Tasmanian students in 1865 (see the table below), she was performing at about Class II, the level of an eight or a nine year old, and probably beyond many of the same age group.

Moreover, Esther’s lessons were of a very different character than what her compatriots would be learning in Tasmanian public schools (see our earlier blog on the Tasmanian curriculum, 150 Years Ago). While those children would be working on strictly the three “R’s” (reading, writing and arithmetic) from Irish National Readers that were at least forty years old, Esther was getting a sampling of not just street ballads, but also geography, at a bare minimum. This wouldn’t be added into the standard curriculum in public schools for another 15 years.

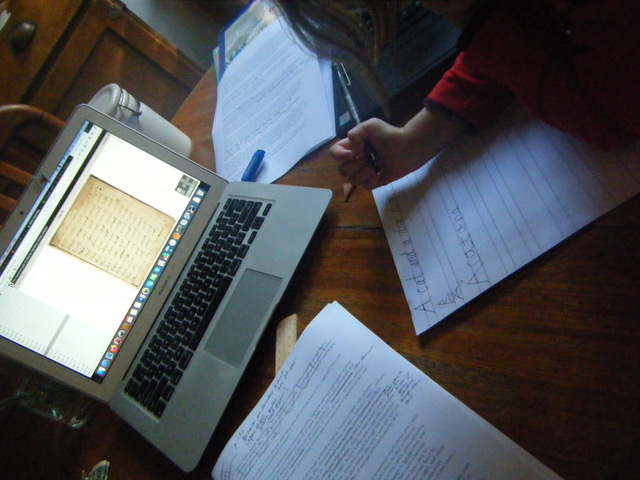

I did actually try this out as part of my own homeschooling journey back in April – setting my own five-year old at the kitchen table, telling her this story, and setting her to do lines while I worked on this research. I can tell you that it took her about 20 minutes to half an hour to complete a page – for which she was liberally rewarded with a long play outside and a rather nice afternoon tea and a story. This, by the way, is why this blog is only being published now that she is back at proper school and receiving a proper education from excellent and highly qualified teachers, not nineteenth-century lines from her eccentric mother, followed by a spirited reading of Moby Dick, seen in the background under an earlier draft…. but I digress.

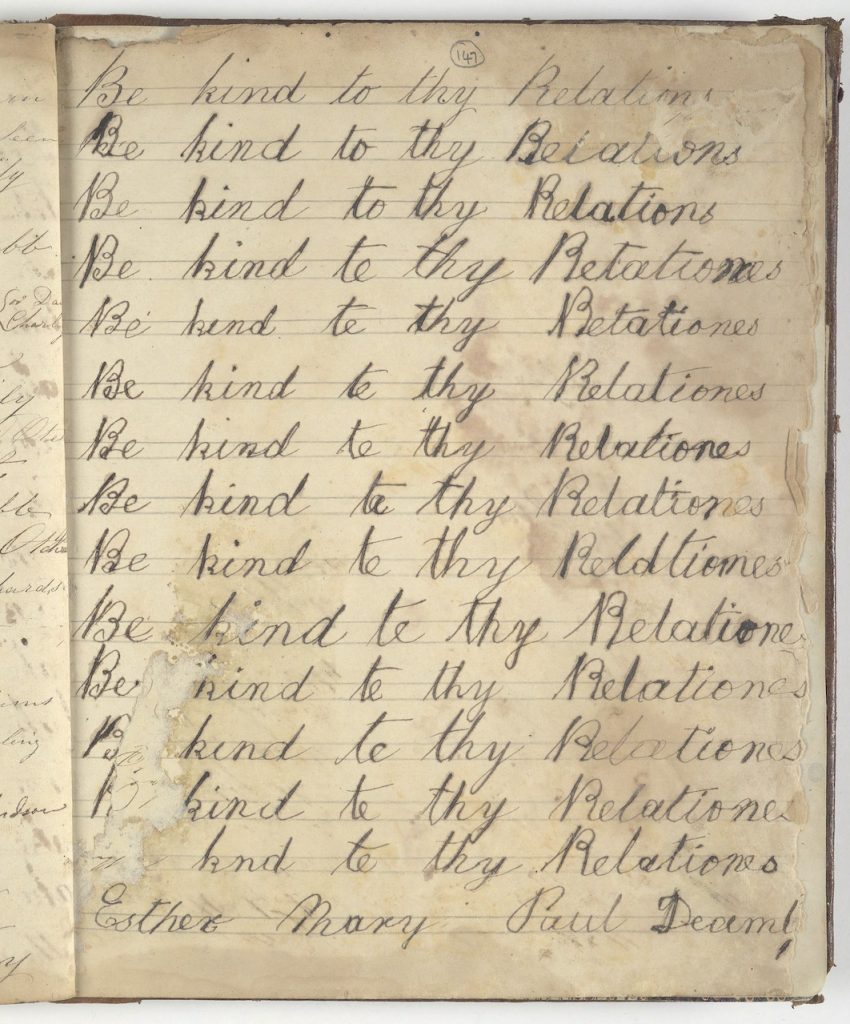

So we know that Esther ended up in a multi-generational household by 1865, living alongside at least her grandmother, her two uncles, and her aunt Charlotte, and possibly her mother and older siblings as well. Her father was gone and her mother (after years of constant pregnancy, hardship, and intense grief) was working to support herself and her youngest child. In the meantime, the bright young Esther was certainly performing at about the standard expected of a child with two or three years of formal public schooling in the 1860s. She was being educated at home, according to a program that seems to have been developed by her family. It was an education that definitely blended discipline (the writing of lines like “Esther shall not go out again”) with much more eclectic stuff, including bawdy limericks and street ballads. But her grandmother, who could not write her own name, would have been able to see the little girl writing lines in her uncle’s logbook- a book which finishes, rather appropriately, with this page of lines “Be Kind to Thy Relations”:

But what about Esther’s father? Where was he, and would he ever reappear? And where would Esther go from here? That part of the story will take us to the Cascades Female Factory in the shadow of Mt Wellington, to an old toll-booth in New Town, and finally to a pharmacy in Launceston at the turn of the century. It’s a story of marriages, attempted murders, abandonment, sorrow, and joy. Tune in next week to find out more.

Further Reading:

If you’re interested in any of these stories, then check out some of our suggestions below. If you need help, can’t visit the State Library in person, or if you’d like a longer bibliography, please get in touch with us! You can always file a research request, and one of our experienced staff can spend up to an hour researching on your behalf (for free!)

Much of this blog depends on the Tasmanian Names Index, our online database of more than a million entries, and a great deal of digitized material. It’s integrated into our catalogue – just search for a name on any page of the website, and start limiting your results. You can also check out our Guides to Records for other ideas and sources that haven’t yet been included in the Names Index. If you need help, just get in touch with us and we can walk you through it over the phone (03 6165 5538).

If you’re also looking for a house or a neighbourhood – whether you’re researching the history of your own house, or trying to put together some historical context around a family story – then have a look at our guide to Researching a Building’s History.

We’ve also digitized some of the Hobart valuation rolls (1853-1890), which I found incredibly helpful while I was working on this story.

Tasmania is rich in excellent social histories, and particularly of Hobart. Here are just a few that you can see in the library that bring some of the areas discussed in this blog to life.

Nicola Goc, Sandy Bay. Sandy Bay, Tas. : Gentrix Publishing, 1997.

It’s also a good idea to go through back issues of local history journals and magazines. They might not all be indexed in the library catalogue, but they are a gold mine of information. If you’re a library member, you have digital access to all the back issues of the Tasmanian Historical Research Association Papers and Proceedings. I drew on this piece to write this story:

Townsley, W. A. Tasmania and the great economic depression, 1858-1872 [online]. Papers and Proceedings: Tasmanian Historical Research Association, Vol. 4, No. 2, July 1955: 35-46.

Many of these histories draw on newspaper accounts, and Trove is a fabulous place to trawl around if you have the time. Check them out here: https://trove.nla.gov.au/

I also went through our old blogs for information on schooling in Tasmania in the 19th century. My colleagues and I put together a series last year to commemorate 150 Years of Public Education in Tasmania, and each of those has plenty of references for you to explore.

I’m a descendant of John Rowland and Cecily Horsley through their youngest daughter Sarah who married Richard Hickman. John and Cecily were living at 17 DeWitt St in 1859 when and where Sarah and Richard were married as the church had not yet been completed to which they were associated. So interesting to read this story. I have seen a photo of 2 lean who I thought were “Paul” girls but can’t place them. So interesting to read how close the extended family to eachother. I have so little in the way of stories of the Rowlands.

Dear Denise, thank you so much for getting in touch! Thank you, too, for the extra information about the Rowland family – it is so gratifying to see the picture develop. I’m glad I was able to give you a little more information for your own research as well. Many thanks, Anna

Hi Anna, I thought I would share a little of what I have found on Esther Mary’s family that is not, as far as I could see, in your story and may help with the great work you have done on Esther Mary.

John and Cecily Eliza Paul must have spent some time in Newtown, Geelong, Victoria as they had 3 children there between 1846 and 1855. They were: Nelson William born 1850, Charlotte Eleanor born 1850 died 1854 in the Geelong Eastern Cemetery C of E old section, Sissly (sic) Sarah born 1853 died 1854 and also in the Geelong Eastern Cemetery C of E old section. This, in my calculations, brings their family number up to the 11 as was reported it may be. I note that their 2nd child, George Smith Paul, named one of his children, born 1870, Esther Mary as well. I am indirectly related to the Paul and Rowland families through marriages to other Tasmanian families, hence my interest. Source for the 3 births above is the Vic. BMD’s.

Thank you so much Robert! This is amazing! I had checked the departures and arrivals for the Paul family but hadn’t found anything – but it explains that big gap in the 1850s, and also the number of children. It also adds a new element to the story – that while Charlotte and William were at sea, Cecelia was also far from home and grieving her children. Thanks so very much for your wonderful work and for sharing with us. It is deeply appreciated!

Hi Anna. Re – Cross St – According to Jarman’s map (1858) it was part of what is now Princes St…I can’t work out how to insert an image – but see Donald Howatson’s 2016 book – The Story of Sandy Bay, Street by Street.

Thank you so much again for your help with that mystery, Felicity! I’ve updated the post.