Tasmania’s Area Schools

In the 1930’s, in the aftermath of the Great Depression, Tasmanian educators came up with a bold new vision to transform rural schools. They wanted to teach the latest in agricultural science, to instil a lifelong love of learning, and to help Tasmanian rural children develop into informed citizens of a modern democracy. They ended up creating a model that was admired around Australia and the world: the Tasmanian Area School.

Rural Schools in the Great Depression

In the 1930s, there were over 650 schools in Tasmania. Many rural schools were in poor repair, isolated, underfunded, and with a high teacher turnover. Low pay, distance and poor accommodation meant that most teachers in rural schools didn’t stay long. The most qualified teachers – the ones trained at the Training College on the Domain in Hobart – stayed in the bigger towns and cities. Most rural teachers had been apprenticed as pupils (some beginning as young as 13) and completed their studies at the Hobart or Launceston High Schools.

The Great Depression made matters much worse. Faced with mass unemployment and widespread poverty, the Education Department stopped maintaining school premises, cut teacher salaries, and imposed fees for secondary school students. Meanwhile, most rural parents resented sending their children off to schools where they weren’t learning practical skills, and might be labelled as “retarded” if they had to repeat a grade.

Options were limited for children who wanted to go to secondary school. The only choices available were at the High Schools in the larger cities (which focused on academic results) and technical schools (which provided training for trades). Both required the children to qualify in order to attend. The majority of children didn’t qualify, and were expected to stay at the primary schools until they were fourteen. If they did qualify, children had to travel to the cities, and only wealthier parents could afford to pay the fees and accommodation costs. With little hope of progress, both rural students and parents became disillusioned and bored.

An Inspiring Idea

In 1934, Tasmania’s Director of Education G.V. Brooks was sponsored to go on a tour of schools in the USA and UK. While on his tour, Director Brooks witnessed a different type of agricultural education in England, one that was available to secondary rural school children and focused on learning practical skills. He was so inspired by this emerging trend that he suggested introducing it to Depression-weary Tasmania. He wrote in The Mercury in 1935,

“I have seen a dozen of these specialised schools, and I was delighted with the work they are doing… The boys were instructed in all types of hand work, wood work, iron work, seeding and other rural activities.”

TREND OF EDUCATION IN BRITAIN AND AMERICA (1935, September 25). The Mercury (Hobart, Tas. : 1860 – 1954), p. 6. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article30107372

In the 1930s, each area of Tasmania with a student population of 20 had been entitled to a teacher and a school, while those with 10 children were entitled to a subsidy. In these English Agricultural schools, transportation was provided to bring the rural children to a centralised school where they could share more resources, have access to rural land and benefit from interaction with more students. By merging small schools into area schools and providing transport between the schools, the Department could make savings in wages, equipment and desperately needed building repairs. As Brooks wrote,

“the spirit of competition was greater too, because there were more children attending the school than there would have been had they attended small schools scattered through their districts, and there was more incentive for them to develop…It seems to me that with very little cost the system could be applied here in Tasmania.”

TREND OF EDUCATION IN BRITAIN AND AMERICA (1935, September 25). The Mercury (Hobart, Tas. : 1860 – 1954), p. 6. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article30107372

An added benefit was that the schools might encourage older children to stay on the land, rather than drift towards the cities where unemployment was high. In his report on the English schools, Brooks noted,

“One of its finest features is its tendency to maintain the youth of the country areas on the land, rather than allow them to drift to the cities.”

TREND OF EDUCATION IN BRITAIN AND AMERICA (1935, September 25). The Mercury (Hobart, Tas. : 1860 – 1954), p. 6. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article30107372

Tasmanian’s Area Farm Schools were officially started as a two year experiment in Sheffield and Hagley in 1935, following Director Brooks’s international tour.

“A School Must Be a Living Community”: The Hagley Model and Tasmanian Innovation

“We are such fortunate children

Born in this beautiful land

Where blossoms fair perfume the air

And all is wondrous and grand

Blue are the towering mountains,

Tall are the gumtrees around,

Tree ferns are seen, tender and green,

Everywhere song birds abound

Chorus

Hagley school song

Sing, sing, yes, let us sing,

Life is a grand and a glorious thing,

Summer and winter and autumn and spring

There is no school like Hagley.

Teachers and communities had been experimenting with agricultural education in state schools as early as the 1920s. Mr. A.P. Meers, the teacher at Riana, established a school farm that attracted “the keenest and widespread interest… all over the district.” In 1929, Meers moved on to Oatlands in central Tasmania (where he also established a school farm), and his work at Riana was taken over by an enthusiastic young teacher, John Stuart Maslin.

By 1929, Maslin was already working closely with the Riana Agricultural Board to introduce agricultural lessons at his school. He had then set up the Hagley Farm School in 1932, which he continued to lead in 1935 when it became the flagship area school for the entire state.

Maslin discussed his educational philosophy and vision for the Area Schools in a 1948 book, Hagley: The Story of a Tasmanian Area School. In the Introduction, he wrote:

“In our School Community the emphasis is laid on achievement and co-operation and not competition. It takes all sorts to make a community. Few reach the lead in the old competitive system based on academic studies, while many, failing in the early race, develop inferiority complexes in which are rooted many of our personal and national ills. By providing an extremely wide range of activities, we endeavour to tap the creative interest of all types of youth. By placing emphasis upon achievement rather than competition, we try to establish some sense of self-confidence and personal pride in very child.

The vital stimulus for achievement is interest. This may be aroused by activities in the garden, the dairy, the desk, the kitchen, the workshop, or on the farm or the stage or any other of the many activities of our School. Our children must be emancipated from the four walls of the classroom and be brought into life while still at school. A school must be a living community.”

J.S. Maslin, Hagley: The story of a Tasmanian Area School. Melbourne, Georgian House, 1948, pp.3-4

The Hagley District Farm School replaced six smaller rural schools. There were 111 students enrolled in 1938, and the average attendance at the school was an impressive 99.8%. Qualified specialist teachers now filled roles previously held by young, untrained teaching assistants.

The rural community appreciated the practical aspects of the school and enjoyed the benefits of the close relationship between the school and the community. Soon other rural communities began requesting their own area farm schools. The Education Department embraced the concept, and wherever it was possible, small one teacher schools were closed and free transport was provided to the nearest area school.

Training Farmers, Educating Citizens

The curriculum in the Area Schools was designed to turn children into both self-sufficient farmers and well-informed citizens. As Maslin wrote,

“If we are to have a virile and real democracy, we must encourage our young people to express themselves logically and to the point on all matters where they can constructively add to the debate.”

Maslin, Hagley: The story of a Tasmanian Area School, 1948

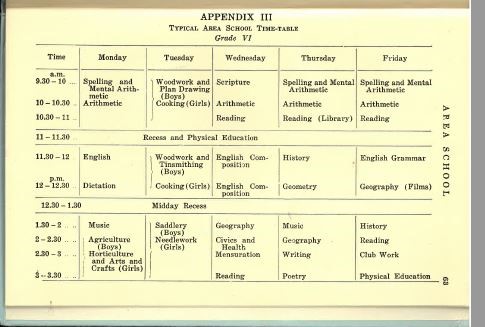

This meant building a curriculum that combined the practical and the academic. It had to blend science, literature, history, rhetoric and art into everyday life on the farm. Most importantly, it had to teach children how to support themselves as well as how to think for themselves. As forward-looking as it was, the curriculum was still very much a product of its time, with sharply different skills taught to girls and boys.

A normal primary curriculum was followed until the students were twelve years old, when the options were split along gender lines. Girls were taught the “Domestic Arts” of cookery, needlework, and home management including first aid and home nursing, laundry work and arts and crafts. They used the produce from the school farm, such as vegetables, eggs, and dairy, to prepare meals for the school canteen.

Boys were taught agriculture, including crop production and animal husbandry as well as woodwork, sheet metal work, building construction, elementary mechanics, leather work, and concrete work. In some schools there were courses in forestry. Boys were also given jobs in the school to train them to be capable handymen. At Hagley, they built sheds, concreted paths, built a chicken shed and pig pens, and fences and garden beds for the girls to grow flowers and vegetables. When the Area School was established at Edith Creek in 1957, local gardener Peter Gnuske “drew up a long-term plan for the gardens, a profusion of shrubs and trees, playing fields and lawns [which] provided a gracious setting for the new school.”

Reading was central to the curriculum. The libraries were well-stocked, and teachers were often generous with their own books as well. In 1988, Elvie Stevensen reminisced that while she was at school at Wesley Vale during the war, that her teacher Miss Verna Pitt used to:

“…[loan] me some of her own books when the library ran dry. From her I learned a little more of the joy, knowledge, and relaxation that can come from books. (She also taught me to do crossword puzzles).”

Portia Andrew, Ponytails & piglets : a hundred years of life at a country school : 1899-1999, p. 67

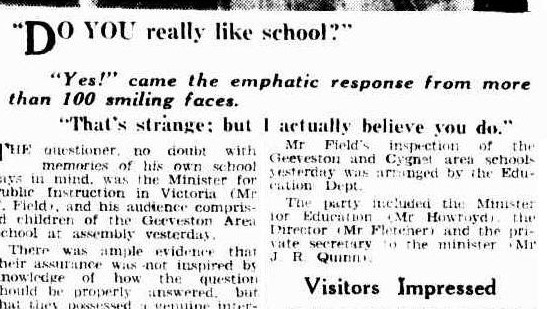

Area school students and staff participated in debates hosted by local Young Farmers or Junior Farmers Clubs, which were reported on in newspapers across the state. The Tasmanian area school model drew visitors from across Australia and the world to check out schools across the state, visits which were reported on in the local newspapers.

Maslin and other Area School principals believed that every child should leave school with a creative ability that would enrich their leisure time. Art, music, science and literature were integrated into daily life. The dining room at Hagley, for example, was decorated with famous art works and children were expected to learn about and discuss them. Miss Mabel Coventry (later Manning) taught at Wesley Vale Area School from 1938 to 1942. She remembered how the headmaster’s wife, Mrs Cobbet, was an accomplished musician who tutored interested students in violin and piano (Andrew, 1999, p. 62-63). Some schools, like Snug, put on concerts organised by students – this one in 1951 packed the Snug hall with appreciative locals.

Everyday life at the area schools

One of the key characteristics of the Area Schools was how closely they worked with local communities. Many of the headmasters and teachers remembered how they worked closely with the community, from the Parents’ Association, the Farm Advisory Board, the CWA and others. They gave practical advice on all topics as well as generous support, and many people took young single teachers in as boarders, which they remembered very fondly.

During World War II, productive school gardens and farms produced much-needed nutrition in times of rationing. Student reports from the Scottsdale District School to the North-Eastern Advertiser regularly discussed food, such as ‘tit bits’ of pork from pigs slaughtered by the boys and:

“Distribution of apples was again welcomed by pupils from both schools this week and a splendid lot formed the first batch, though so most them are so big the kindergarten children find them a meal.”

SCHOOL NOTES (1943, April 16). North-Eastern Advertiser (Scottsdale, Tas. : 1909 – 1954), p. 3. Retrieved November 12, 2019, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article151468992

Teachers and pupils often recalled cycling long distances to school, “Hail, rain or shine” which was especially unpleasant during wartime (and postwar) rationing when you had a worn out rain jacket and no clothing coupon to get a new one! As Mabel Manning recalled in 1999,

“The metal roads were in very poor condition and it made riding a bike very hard work, and jarred every bone in one’s body, but I was happy to do this as I loved the teaching situation so much.”

Andrew, 1999, Ponytails & Piglets, 63

Mrs Manning later remembered “Many of the young ones [walked] several miles to school, some helping with the milking before they left home.” Many others took the bus, sometimes for very long distances.

In 1999, when she was eighty years old, Mrs Manning also reflected,

“How strict we were in those days. Discipline was first and foremost and we expected so much from our young pupils. I hope they have benefited and do not resent the harshness, but remember the fun, the love, and the good times.”

Andrew, 1999, Ponytails & Piglets, 65

That combination of “harshness” and “good times” – is reflected in this amateur video, shot in 1945 by Ron Brown. He visited the Huonville Area School and recorded (in silence) many everyday moments – children arriving at school on cycles and buses, going to “physical culture” class, going to the beach in Sandy Bay, and other everyday moments at school. But then, at the 3:04 mark, a teacher canes a young boy on his hands, front and back – while his classmates look on and laugh, and the little boy tries not to flinch. The moment seems to have inspired the title that Mr Brown gave the video – “Kid whacking” – and it illustrates an school experience – and indeed, a world view – that has changed a great deal in 70 years.

“Kid Whacking – a Day in the Life of Huonville Area School.” 1945-1946, by Ron H. Brown. Tasmanian Archives: NS1529/1/10

Decline of the Area Schools

Area Schools served a wide population, incorporating infant schools, kindergartens, primary and post-primary education. While the model was admired by many (including many teachers who longed to be posted to area schools) at the same time, it had its limitations. Those students who were identified as being academically gifted were encouraged to apply to high schools in the cities. Secondary education was selective, and in order to attend, students had to pass exams and, if they were accepted, move away from home.

As Michael Sprod wrote in the Companion to Tasmanian History, in the postwar period,

“ It was becoming increasingly apparent that the area schools, by preparing them so well for rural life, made it difficult for students to aspire to any career other than a farmer, or a farmer’s wife…. With the rapidly-expanding post-war economy, the notion that educational opportunities should remain open and available equally to all had become widely accepted, especially among parents. The area schools were progressively transformed into district (primary) schools, or district high schools, and the modern schools into high schools “

Michael Sprod, “Area Schools” Companion to Tasmanian History, 2005, p 25.

This shift came to Huonville in 1956 with its participation in a trial of the comprehensive high school model, which would allow more of the area’s academic students to remain in the area, rather than being removed to the selective high schools in Hobart. By the end of the 1950s, the success of non-selective district high schools was being celebrated.

“The idea of the non-selective district high school is becoming a well-established trend of secondary education taking place in this State and the teachers concerned in the development of these schools are deserving of special commendation for the constructive way in which they have co-operatively approached the many problems involved. These district schools continue to win the active support of parents and throughout the year the scope and quality of lay participation was an outstanding feature of their development.”

(Journals and printed papers of the Parliament of Tasmania. 1959. Education Report no.45)

While the area schools gradually shifted, today the Hagley Farm School is still a thriving example of practical, agricultural education. The school complex has expanded to include a visitors centre to accommodate visiting school groups, allowing a wider pool of students to learn the lessons of a farm environment.

Further Reading

Explore 150 years of public education in Tasmania

Library Items

Christine J. Harper, ed. The way we were : Edith Creek Area School. C. Harper, 1989.

J.S. Maslin, Hagley : the story of a Tasmanian Area School. Melbourne : Georgian House, 1948.

Michael Sprod, “Area Schools” in Alison Alexander (ed), The Companion to Tasmanian History. Hobart: Centre for Tasmanian Historical Studies, University of Tasmania, 2005, 25. Also online at https://www.utas.edu.au/library/companion_to_tasmanian_history/A/Area%20schools.htm

Archival Material

The Tasmanian Archives holds a vast number of records that were created by, for, and about Tasmania’s Area Schools. Just type “Area School” into the library catalogue and you’ll come up with thousands of results from across Tasmania. You can also look for a particular school, just type in the name and see what comes up. For more help (and also for a great list of useful series), please see our guide to records on Schools and Education here: https://libraries.tas.gov.au/family-history/Pages/Education.aspx

Please note that some of this material may be restricted, especially if it contains private information about students and their families. Check the access restrictions before you order, and if you are confused, please call us on (03) 6165 5538 and we’ll explain it.

Authors

This blog has been a long time in the making, and a number of members of the State Library and Archives Team have contributed to it. Librarian Elizabeth Brown conducted most of the research and wrote most of the material, with valuable contributions from Anthony Black. Archivists Jessica Walters and Anna Claydon edited their material and supplemented it in places.

I did my first three years at Sprent Area School. We travelled from Kindred in the old Bedford bus. This was better than the Nietta kids who came in an old Maple bus and the Gawler kids who had an old Chev with a canvas roof panel that sometimes fell down.

“Yes Sir”, In the 1950s respect, politeness and discipline were normal and accepted. Teachers were called as Mr, Mrs or Miss.

Outdoor exercise in the play area on monkey bars, swings and climbing towers. Equipment that today would be considered almost dangerous, did us very little harm at all.

Morning assemblies, with students and teachers singing the Royal National Anthem and even saying the Lord’s Prayer is a far cry from school today.

I believe the structured discipline plus the care we each received and lessons around the “3 Rs” prepared us much better for our teenage and adolescent years ahead.

Thank you, John, for your thoughts and your reminiscences of Sprent Area School. We do appreciate it!