Isn’t it good, Taswegian Wood: Experiments in Growing Cricket Bat Willow Trees and a Wooden Cricket Pitch

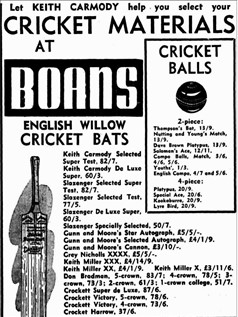

In the 1930s and 40s cricket bats were a precious thing. Around the world, bats were in short supply, largely due to an increase in demand for English willow (Salix alba var. caerulea) for use in a range of items both during and after the Second World War. As was noted in correspondence between J. M. Crockett and The Commissioner of the Australian Council of Agriculture in July 1940:

every available tree of this type has been taken over in Gt Britain for War Purposes, the chief item being aircraft construction, the timber being the best substitute for spruce, which is all tied up now in countries occupied by the enemy … The other uses for this willow is artificial limbs for which no other timber is suitable, and recently has [been found to have] the quickest, and most powerful detonation as a component in high explosive fuses for shells … So you can see that none of the tree is not of high commercial value.

As a cricket bat manufacturer, J. M. Crockett (Jim) had obvious motives in writing to the Commissioner and highlighting both the current global willow shortages and the value of willow timber more broadly; he wanted to propose the planting of willow trees as a viable and profitable agricultural activity in Australia. As Jim Crockett continues in his letter, ‘in normal times Australia’s requirements alone is 100,000 cricket bats annually, for which 4,500 mature trees would be required to produce the same.’ Kashmiri willow, which today is a major source of cricket bat willow, had not yet been fully developed as an industry outside of India, and so the bat-making industry was having to look further afield to other sources of willow. Australia, and most particularly the cooler and wetter climate of Tasmania, was certainly a strong option worth exploring. Over the next few years Jim Crockett made several visits to Tasmania, noting the ‘climatic conditions ideal’ for willow bat propagation. Indeed, he went so far as to state that ‘not only could Tasmania make Australia self-sufficient, but an export trade to the empire’s cricketing Dominions was extremely likely.’

Within several months of writing his letter to the Commissioner, R.M. Crockett & Son Pty Ltd received an order from the Tasmanian Forestry Department, and by September 1940, 1000 ‘cricket bat willow cuttings’ were being cared for in a plant nursery in the North West. These cuttings were in high demand; the Tasmanian Producers Association based in Longford, enquired as to the cuttings’ availability, and estimated in May 1941 that there were roughly 100 miles of river frontage amongst their landowning members for growing bat willow.

A Melbourne-based company, R.M. Crockett & Son was founded by Jim’s father Robert Maxwell Crockett (d. 1935) who was a record-holding Test match umpire. The story goes that Robert was umpiring a match between Australia and England, when the English captain Archie MacLaren mentioned that he was surprised ‘that you do not grow the bat willow in this country.’ Upon his return to Britain, Archie MacLaren sent Robert some willow cuttings, of which only one survived the journey. It was duly planted at Shepherds Flats in Victoria. R.M. Crockett & Son Pty Ltd was established in the years following, and operated in various forms until 1972, when it was wholly taken over by Slazenger. (Haigh, Silent Revolutions: Writings on Cricket History, p.89).

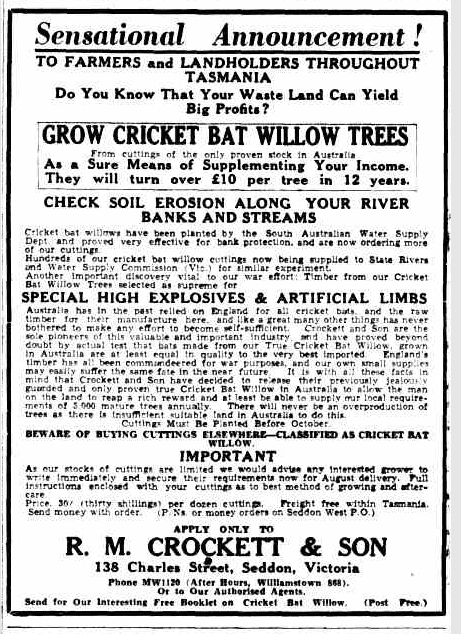

Tasmanian Forestry Commission records held within the Tasmanian Archive, notably the series FC4 and FC5– General Correspondence, reveal the negotiations with R.M. Crockett & Son, and also internal communications and research around the growing and propagating of bat willow in Tasmania. These records reveal several things of note; firstly, it was widely advertised in Tasmanian newspapers that bat willow could be grown on riverbanks, or on unproductive, waste pastural wasteland as a sideline agricultural activity; this was hotly disputed. As a plant pathologist J. O. Henrick pointed out in a letter to the Secretary for Agriculture in Hobart in August 1941, “it has been noted that a ‘sensational announcement to farmers throughout Tasmania’ has appeared in the Mercury of 2.8.41 and represents that they will make big profits in 12 years on waste land. This is not so. The land must be fertile, must not be waterlogged and it will make 15 years or more for the timber to mature.’ So growing bat willow was perhaps not quite as simple as the advertisement would suggest.

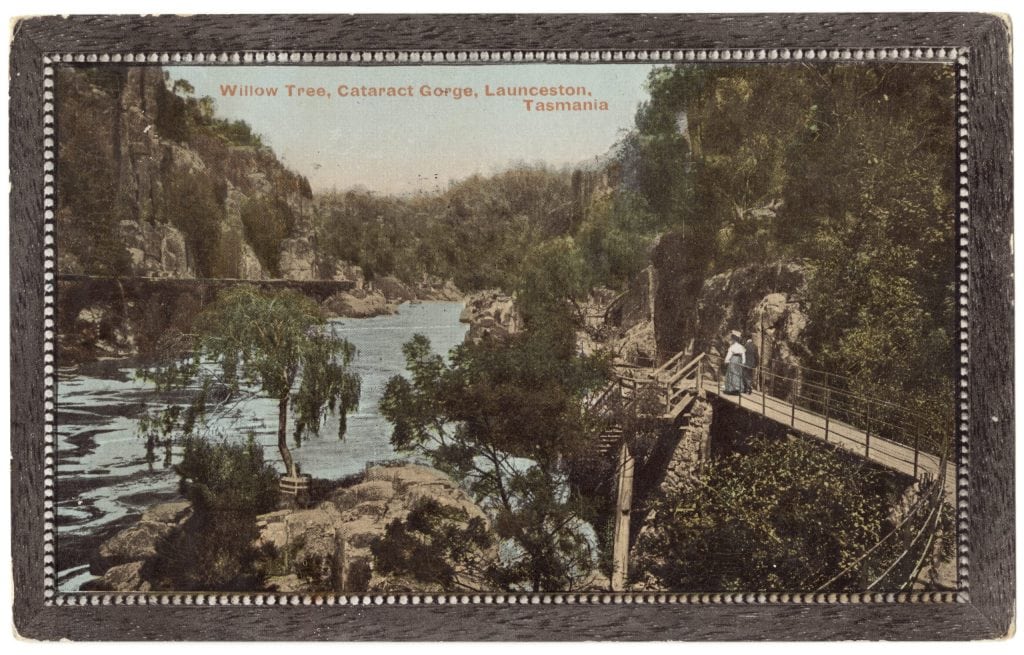

Furthermore, Tasmanian Forestry Commission records reveal that this was not the first time that attempts had been made to grow willows for bat production in Tasmania. Nine years earlier, in December 1931, cricket bat willow cuttings had arrived from England, however, they arrived in a ‘wretched condition’ and at the wrong time of year. The cuttings were at Forestry plant nurseries around the state, where they were expected to be cared for around four years, before being grown out. By May 1933, there were ‘very few left.’ Unfortunately, not all species of willows proved difficult to grow in Tasmania, and they are now a ‘serious environmental weed’, and you will find them choking our waterways around the state.

So, was a cricket bat ever produced from Tasmanian-grown willow? Well, we’re really not too sure; it would appear that Emu Bats (sometimes known as Tattersall Bats) produced bats from Tasmanian willow in their joinery in Burnie in the 1930s. There is an example of an Emu bat held in the Tasmanian Cricket Museum & Library which has the signatures of the English cricket team of 1932-33 and 1954-55 on it. However, the origins of this willow will need further investigating. The last that we hear of cricket bat willow in the Forestry Commission records is in a letter from farmer W.R. Kirkland of Rowella to the Conservator of Forests in August 1951, enquiring as to the availably of cuttings. It does not mention whether these are the Crockett & Son cuttings purchased in 1941; the last that we hear of these cuttings in the archive is in August 1944, when the Conservator of Forests wrote to the Hon. Minister for Forests to report that ‘at present we have approximately 1,300 rooted cuttings of cricket bat willow in the nursery at Myrtle Grove.’ However, the letter continues that ‘it was anticipated that these would be available for planning out this season, but [it was delayed as] growth was not up to expectations.

Maybe these cricket bat willow are still growing around Tasmania today?

A Wooden Cricket Pitch in a Desolate Landscape

While researching bat willow growing in Tasmania, I found an intriguing black and white image of a gentleman holding a hat, standing on some planks of wood in a tree-less landscape that is surprising flat for Tasmania. The title of the image simply reads: ‘Thwaites standing on old wooden cricket pitch, Skittleball Plains near Little Pine Lagoon”. The man in the image is Jack Thwaites (1902-1986) – a renowned Tasmanian photographer and conservationist- whose important collection of photographs and negatives along with family archival items, resides with the Tasmanian Archive Collection.

Wait, what? A Wooden Cricket Pitch?

Yes, a wooden cricket pitch, which must surely have been a bowler’s delight. Jack Thwaites was obviously fascinated by it, so much so that he stood in the centre of the pitch to have his photo taken. Three years after the photograph, Thwaites wrote a short social history of the Steppes and surrounding area in The Tasmanian Tramp: Magazine of the History Walking Club (Volume 22, 1976), which he was to publish as a short pamphlet in 1985. Writing of the wooden cricket pitch of Skittleball plains Thwaites writes:

The Lake Country shepherds were a resourceful lot and had their share of fun too. A number of them who were fond of cricket laid down their own pitch on the Skittleball Plains. After clearing and levelling the area and building a shed for a pavilion they laid down a pitch of slabs, twelve inches wide and four inches in thickness, adzed off to a level surface. This pitch is said to have played very fast when wet. They were able to must up enough men to enjoy their own brand of cricket. Jack Thwaites, The Steppes: Life in Tasmania’s Lake Country (no page numbers).

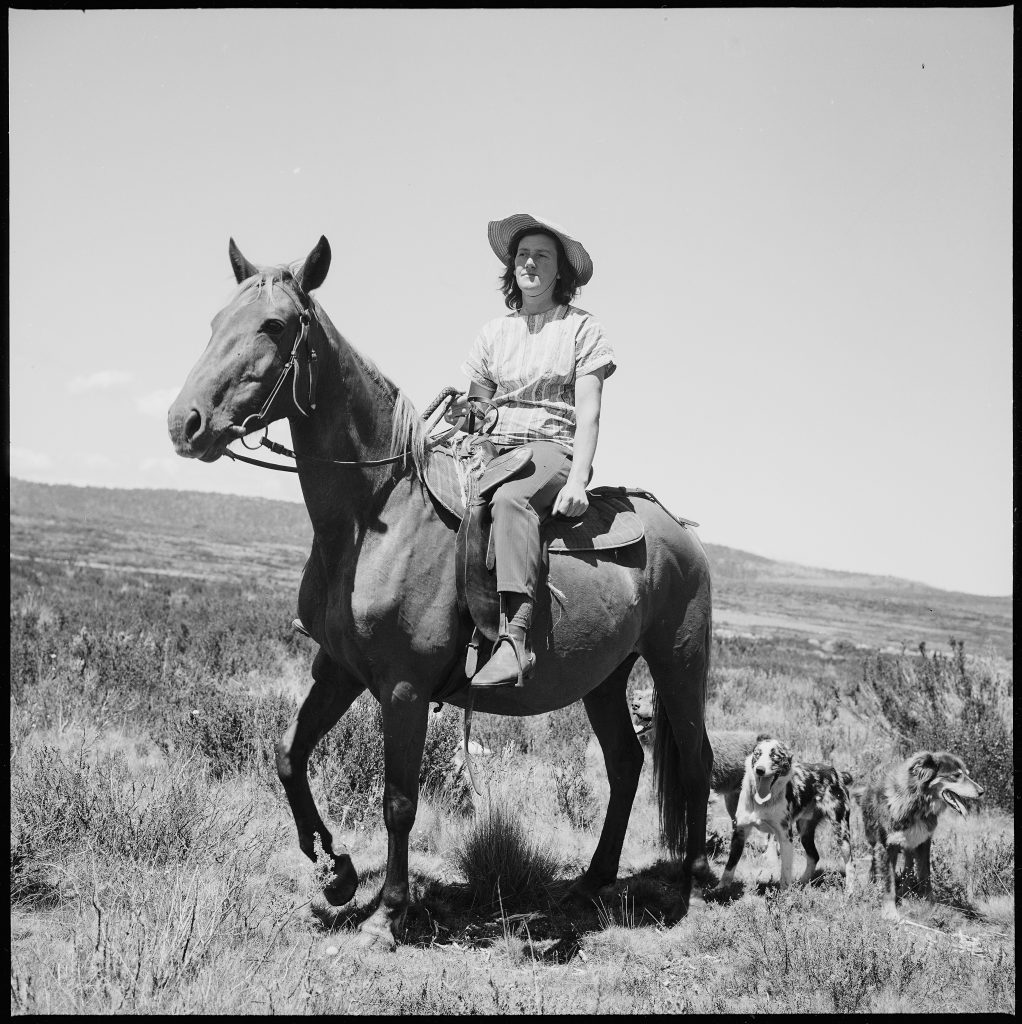

The strange landscape of Skittleball Plains seems to have captivated the Thwaites family, their visits in 1957 and 1973 documented in two series of photographs. These images depict a sparse and desolate landscape, with low-lying vegetation, and odd geological formations of spherical rock (the Skittleballs) that are dotted on the hills surrounding Little Pine Lagoon. These images really highlight the isolation in which this wooden cricket pitch was built. Skittleball Plains is located at the very heart of Tasmania, located around 10 kilometres south-west of the Great Lake in the Central Highlands.

The people who lived and worked in this strange landscape were also a focus of the Thwaites’ photographs, with several images capturing the social history of Skittleball Plains. In addition to photographs of the wooden cricket pitch and the pavilion, there is a photograph of a shepherdess by the name of Amy Pulford on her horse, with her working dogs alongside her.

In her history of the Lake Country, historian Gwen Hardstaff writes that the wooden cricket pitch was constructed in the early 1940s; interestingly, this makes the pitch a contemporary of Crockett & Son’s push into Tasmania in their quest for growing cricket willow. Prior to the construction of the wooden pitch, a dirt pitch was located on the banks of the lagoon, however, this was very unreliable, with dust created in hot and dry weather, and mud when it rained (Hardstaff, Cider Gums & Currawongs, p.48). This earlier cricket pitch was located on the south-eastern upper shore of Little Pine Lagoon, which today is still known as ‘cricket pitch shore.’ The wooden cricket pitch was built away from the lagoon, closer to the Skittleball Plains homestead by Bill Johns, who was the tenant of Skittleball Plains from the 1930s (Hardstaff, Cider Gums & Currawongs, p.257), and his brother-in-law, Basil Baker. The materials for the pitch came from some disused wooden remnants from a nearby bridge over the Ouse River. Around the same time, the pavilion was built for the comfort of the cricketers and spectators. Like Jack Thwaites, Gwen Hardstaff too notes that the wooden surface was very fast, and could be dangerous; she notes that Bill was struck by a ball from which he received a scar. (Hardstaff, Cider Gums & Currawongs, p.49).

It is worth noting that in the 1940s different sorts of cricket pitches were being trialled around the world as alternatives to the traditional grass. As The Examiner explains in 1949, the London City Council and the Marylebone Cricket Club were experimenting with cork, matting, and peat as well as asphalt, rubber and wood, ‘in quest of a pitch which will “behave like good grass without wearing into potholes under the tread of myriad feet.” The wooden pitch at Skittleball Plains, in the centre of Tasmania, really was a world-leader in innovation!

It is difficult to know whether the wooden cricket pitch survives to this day. Devastating fires swept through Skittleball Plains in January 2019, and the Skittleball Plain homestead was lost and the surrounding area was burnt. At least we have this photograph to tell us of its existence, and we can conjure up images of quiet high country life broken up by the excitement of a friendly Sunday afternoon cricket match.

Bibliography

Tasmanian Archival Sources

FC5/1/1200 AN 1216. Forestry Department. Reports on areas suitable for establishment of nurseries for the propagation of cricket bat willows. (Index No Management 2 File No 7480) (1931-1938)

FC5/1/641 AN 642. Forestry Department. Silviculture of cricket bat Willow (Salia alba vars). (Index No Silviculture 3 File No 2283) (1931-1941)

AD9/1/2707 13/7 Forestry – Planting of Willows for Cricket Bat manufacture (1939-1940)

AD9/1/3399 13/7 Forestry – Cricket Bat Willow (1941)

FC4/1/70 Arboriculture 5/8. Farm Forestry. Cricket Bat Willows. (1941-1952)

FC5/1/1202 AN 1218. Forestry Department. Senator C A Lamp. Information about the proposal to establish plantations of cricket bat willow in Tasmania. (Index No Management 2 File No 7483) (1944)

AD9/1/2707 13/7 Forestry – Planting of Willows for Cricket Bat manufacture (1939-40)

NG1155 Jack Thwaites and Family Collection (1902-1986)

State Library Resources

Gwen Hardstaff, Cider gums & currawongs : a history of lifestyle, people and places : the Lake Country of Tasmania to the 1950s (Hobart, Tas.:Forty Degrees South, 2010.)

Simon Kleinig, Jack Thwaites : Pioneer Tasmanian Bushwalker & Conservationist (Lindisfarne, Tas. : Forty Degrees South, c2008.)

Roger Page, A History of Tasmanian Cricket (Hobart : Govt. Printer, [1957].)

Jack Thwaites, The Steppes: Life in Tasmania’s Lake Country (Hobart: Hobart Walking Club, [1985?])

Hi Jilli, thank you for your fascinating comment. I did not know about the hazelnut trials, thanks so much!

The Alexander Racquet Co Factory ( Now the Police Boys Club at Newstead) apart from the famous Alexander Tennis racquet also made cricket bats from willow which I believe came from the

Hollybank Nursery near Lilydale. I purchased one from their closing down sale in mid 50`s.

I don`t think the willow cricket bats was a successful venture for them.

My then husband and I bought a 12 acre property on the creekside of Summerleas Road, Kingston in 1977 (which we sold some 5 years later).

Our creekside meadow had a half acre stand of willows. We were told by locals that they were the remnants of those once grown for the cricket bat industry. This article puts that family story in perfect context. I had always been under the impression that willow was imported into Tasmania to plant as fire breaks along creeks and to hold the banks. There’s also a story that the first willows into Tasmania came from the Island of St Helena, and were planted along the river at New Norfolk.

As an aside, there is also an early history of trying to grow a hazelnut industry in southern Tas, which failed. We wanted to plant them in the 70s but couldn’t find them. In the 90s, DPIWI was supporting a re-try at commercial hazelnuts, along with olives. The olives have been a great success but as far as I know, not so the hazels.

My partner also bought cricket bat willows from Scottsdale nursery about 25 years ago, as an investment and he is a cricket tragic. He was under the impression it would be around 12 years before they were big enough to harvest, but they have taken all this time to grow!

They are now about the right size to harvest, around 60 trees in total, the problem is finding someone to turn them into cricket bats. Certainly not a fast money making venture.

Oh my, this is a wonderful story Ruth- 25 years later! Thank you for sharing it. I would be fascinated to know if the produced wood will be good enough for a cricket bat, as I understand that the quality of the wood depends very much on it growing quickly. Regardless, I hope that he finds someone as they would be terrific!

Hi Ruth,

I am a Cricket bat maker and repairer based in Launceston (TAS) and currently order my willow from international suppliers. I would be interested in discussing your willow.

What a fascinating article. Thanks for your well-presented research.

Thank you Colin, I appreciate your comment. All the best, Ali

What a very interesting article and lovely old photos, I wondered about that strange looking rock in photograph 73/28 above, and found this: https://eprints.utas.edu.au/14567/4/General_geology.pdf

I guess they were called skittleballs because it’s less of a mouthfull than ‘tor of scoriaceous tholeiitic basalt’!

PS The article’s title, a play on the Lennon / McCartney song ‘Norwegian Wood’ which has an interesting last 2 lines “So I lit a fire, Isn’t it good Norwegian wood? I think it’s a revenge song!

Hi David, Aren’t the skittleballs fascinating, such an interesting geological formation! It really adds to the strangeness of the cricket pitch’s location. And yes, it really is a revenge song, he must have woken up feeling a bit cold and shunned … Many thanks, Ali

Probably 35 years back, Woodlea Nursery, out from Scottsdale, acquired cricket bat willow cuttings, to attempt establishing an industry. As far as I know, none of the plantings were successful in producing quality wood for bat manufacture, as the growth rate was too slow.

The planting material was provided as potted, rooted cuttings, which ,in my opinion, was not a necessary step in establishment. Some of the “cuttings” became separated from their roots when removing them from the pots, these ones, I trimmed off with secateurs and those trees were the most successful in producing a barrel near adequate for suitability to produce a bat.

Most of the small plantation has been cleared, with possibly just a couple of dozen trees remaining.

Dear Rob, thank you so much for your comment. This is really interesting, and so great to find someone who worked with the cricket bat willow trees. There is lots of discussion in the forestry records of the 1940s and 1950s about the slow growing of the bat willow cuttings, and so I am so pleased to hear of your first hand experience of this too.