From “Dangerously Foul Air” to Free School Milk: A Brief History of Public Health in Tasmanian Public Schools, 1900-1975

Schools with no toilets and no sinks to wash your hands. Sick children labelled as “mentally deficient” because of their swollen adenoids and tonsils. Adolescents with a full set of dentures, little children cleaning their teeth with the corner of a sooty towel. A generation of teenagers with curved spines and poor eyesight from bending over their school desks in poorly lit and freezing cold classrooms. This was the picture of public health in Tasmanian schools in 1906. Over the next 75 years, schools found themselves on the front lines of the battle against contagious disease, poor nutrition and poor health. Over time, Tasmanian public schools became a crucial part of the Tasmanian public health system, and transformed the lives of thousands of Tasmanian children. Read on to find out more about this fascinating story.

Sickly Schools and “Neglectful” Parents: Tasmanian Public Schools c. 1900

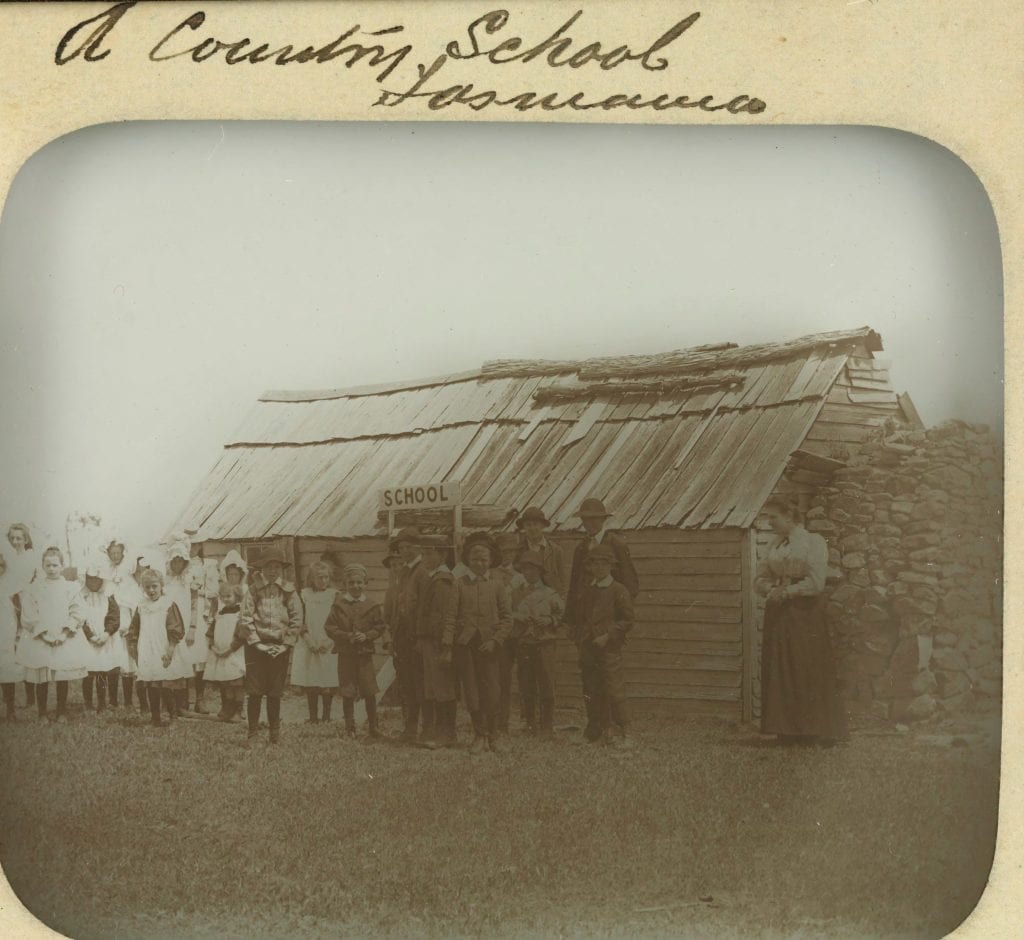

In 1904 the Government of Tasmania invited W.L. Neale (a highly-regarded Inspector of Schools in South Australia) to report on the system of primary education in Tasmania. Neale’s report on Tasmanian schools covered teachers’ qualifications (or lack thereof), teachers’ pay and conditions, school attendance, teaching methods, school standards, discipline and the use of corporal punishment – all of which makes fascinating reading. It was what Neale discovered about the schools themselves – and how they were contributing to poor student health – that’s important here. Section XII of his report focussed on the school buildings and their effect on children’s health, and Mr Neale found,

- “In no school room did I find adequate ventilation…. In the majority of rooms the air was dangerously foul.”

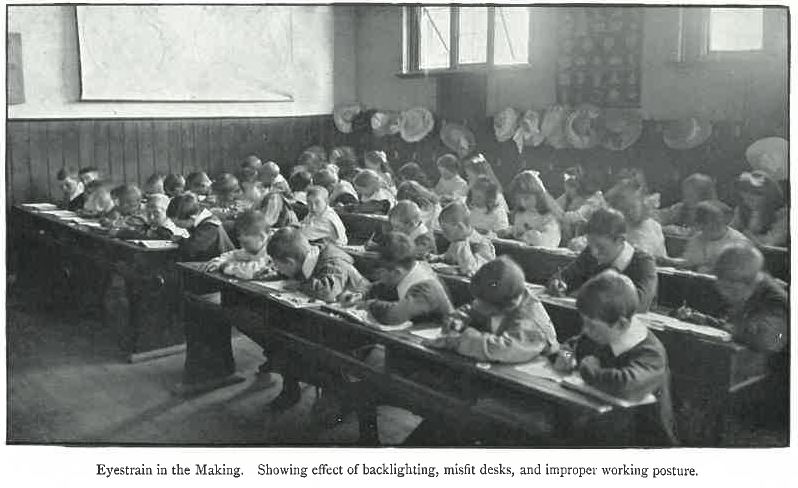

- Lighting was poor and this “was often responsible for the destruction of valuable eyesight”

- In some of the country schools, urinals were a “positive menace to health”

- Not even a single washbowl, (for children to wash their hands) or stand for one had been provided.

- Hats and cloaks (often wet and smelling) were hung in the classrooms, thus creating damp and unhealthy conditions.

- Desks and chairs were the same size for the infants as for the older children, causing problems with posture and interfering with their development.

- It was often difficult for the children to see the teacher and the blackboard and the teacher to see the children.

Perhaps as a result of this, “It is not uncommon to see the teachers of all grades working with canes in their hands.”

Following Mr Neale’s report the Tasmanian Parliament asked the Chief Health Officer of Tasmania, Dr J.S.C. Elkington to conduct an enquiry into the health of Tasmania’s school children. He found that the schools were contributing to bad posture and poor eyesight, that sick children were being labelled “mentally defective” and that in his view, children were overwhelmingly dirty and neglected by their parents.

Dr Elkington’s report in 1906 agreed with Neale – the schools themselves were the source of much misery and disease. He wrote,

“in some of the country schools, urinals and out-offices were a positive menace to health…” [There was an] “almost entire absence of proper lavatory accommodation… not even a single washbowl or stand for one has been provided.”

J.S.C. Elkington, Health in the Schools, or, Hygiene for Teachers, 1907.

He revealed that Tasmanian school girls had marked curvature of the spine, or “weak backs” and he had no doubt this was “due to defective lighting and desking.” Eye tests revealed that almost half of the children had poor vision which got worse after age 6. Poor vision was given as one reason boys were leaving school at age 12, and for girls who left at age 14. These eye problems were attributed to the “enormous strain placed upon them in the early stage, when the eye is most plastic and most liable to damage,” and to the very poor lighting in the schools.

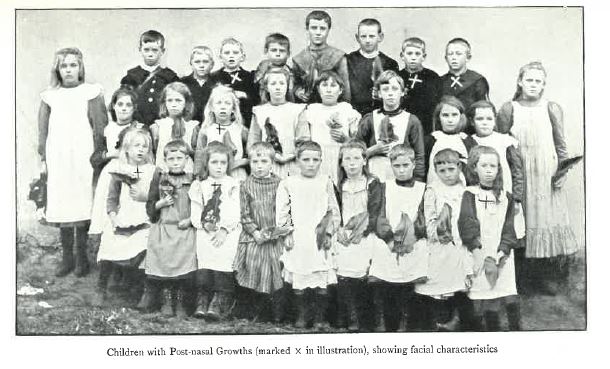

The problems were more systemic, though. About 33% of the children suffered from swollen adenoids. Adenoids are lumps of tissue at the back of the nose that help young children fight infection, and they usually disappear by the time children become teenagers. They can become swollen and infected, particularly if children suffer from constant coughs and colds. The result is often that children breathe through their mouths, sleep badly, and are subject to still more infections. In Tasmanian public schools at the turn of the century, these children were often labelled “dull and defective,” probably because they were so tired and sick. Elkington wrote that a simple operation and the child’s absence from school for only a few days would, in many cases, transform their lives.

With regard to the children’s teeth, Dr Elkington reported, “… there is probably no more prolific source of ill-health and underdevelopment in later life than that arising from seriously decayed and defective teeth during childhood and adolescence.” 94% of the 1207 children Dr Elkington examined required dental work – either fillings or extractions with over 30 % of the children’s mouths in a “dangerously foul condition.” Boys’ teeth were worse than girls’ teeth and many children in secondary schools had their secondary teeth removed due to infections. Some had full dentures. The children reported cleaning their teeth with the corner of a towel, sometimes adding salt or soot for a better effect.

Tasmania was at that time paying the least amount per capita for education and was Australia’s poorest state, so unfortunately the aim of Parliament was to find ways to save money on education, not to spend it. So there was one aspect of Elkington’s report that the Education Board seized on with relish – his attacks on parents for poor hygiene and neglect. Dr Elkington’s report bluntly stated, “A dirty body means parental incapacity and ignorance. Dirty clothing means neglect at home.” On the day of the inspection, 62% of the children had worn dirty clothing to school and 75% had been dirty in body.

To alleviate this problem Dr Elkington produced a booklet, Health Reader: with chapters on elementary school hygiene, which was illustrated by Norman Lindsay. It contained advice to parents on how to keep their homes clean and tidy. emphasizing that they were responsible for the energy and vitality of their children.

Fresh Air and Exercise!

Dr Elkington pointed out that school hygiene could be managed with changed behaviors instead of large expenses. He advocated ventilating school rooms, eliminating coal fires in the classrooms, not using tallow candles for lighting, keeping the air pure by cleaning drains and keeping rubbish heaps away from the schools. He further advised cleaning the windows and using “daylight reflectors” to help with the children’s visibility. The school rooms must be kept spotlessly clean. Carbolic acids should be used and kept out of reach of the children. A helpful appendix in the treatment of poisoning was added to his manual for teachers.

Meanwhile Mr Neale, now Director of Education in Tasmania, was using his new publication the Educational Record, to encourage teachers to conduct regular vision and hearing tests for the children urging them to test the hearing and eyesight of every “dull” and “inattentive” child. [His emphasis] He advocated a rotational appointment of a child to be sanitary officer. The child would be responsible for opening windows for ventilation and pointing out areas of dust and filth to the teacher.

The only physical education for children when Neale took office was military drills for boys, which were supposed to help develop discipline and prepare the children to go to war. As the North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times frankly pointed out in 1901, “The children of the present may help materially sustain the prestige, aye, the very existence of the Empire in future years.” Neale changed this practice, engaging Mr Christian Bjelke- Petersen to give a mid-winter course in Physical Culture to teachers in Hobart. Arrangements could be made for interested teachers to attend from other areas of the State. Bjelke-Petersen also introduced a new regime which included exercises for girls, which was the first time that their needs had been considered. As an interesting side note, Bjelke-Petersen’s sister Marie was also the subject of another of our blogs – have a look at “Jewelled Nights: The Surprising Story of Two Tasmanian Women and their Lost Silent Film”.

The School Medical Service

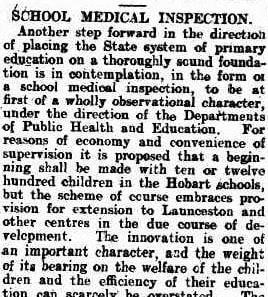

It was Director Neale who introduced the medical inspection of school children, a practise that was continued on by his successor W.T. McCoy, who in 1909 advertised positions vacant for Female Medical Inspectors of Schools. The applicants were to provide medical examinations of the children and report on the hygiene conditions of the schools. They would also provide instruction to the teachers in hygiene matters and provide lectures to the elder girls and mothers. Applicants were to furnish evidence of their knowledge of infectious diseases and their prevention, and ear, eye and throat study. A salary of 250 pounds per annum was offered with increments of 25 pounds a year to a total of 300 pounds per annum. Travel expenses would be paid.

When a new child started school a health card was completed by the head teacher. The card showed the child’s weight and height, the results of their eye and hearing test, detailed any physical peculiarities and gave a history of any diseases. These cards were amended annually showing changes in height and weight. (Unfortunately no health cards from this period have survived in the Archives).

The School Medical Service was abolished during the Depression years to save money, but mothers fought to reinstate it. At the forefront of the fight was Mrs Edith Alice Waterworth, a vocal advocate for women’s and children’s health and education from the 1920s to the 1950s. As a member of the Mother and Child Council of Tasmania, she wrote to the Mercury in 1941 urging the reinstatement of the School Medical Service.

As the Mother and Child Council is deeply concerned about the health of schoolchildren an inquiry was made as to inspection of schools. We were informed that 90 out of the 450 has been examined during the past two years. With the permission of the Minister for Education we sent out 361 circulars. We received 215 replies that stated that 163 schools 75% had had no doctor’s visit for seven years or longer. These included some of Tasmania’s largest schools, for where there is no Government Medical Officer there is no inspection”

Edith A. Waterworth, “School Medical Service,” The Mercury, 26 November 1941: 3

Writing after the war, Mrs Waterworth called the abolition of the medical service a sign of “an all-time low of national intelligence” which had seriously harmed Tasmania’s children, leaving them open to infection from diseases like TB. She claimed that when the service resumed, surveys showed definite signs of malnutrition in 20-45% of the children. This was mainly due to a poor diet, not a lack of food. Ignorance about nutrition, combined with a lack of access to fresh seasonal food, was an ongoing problem. Tasmania was worse than the mainland states and there was a lack of green vegetables available in the country areas. It was recommended that senior girls should all be taught nutrition and hygiene in the schools.

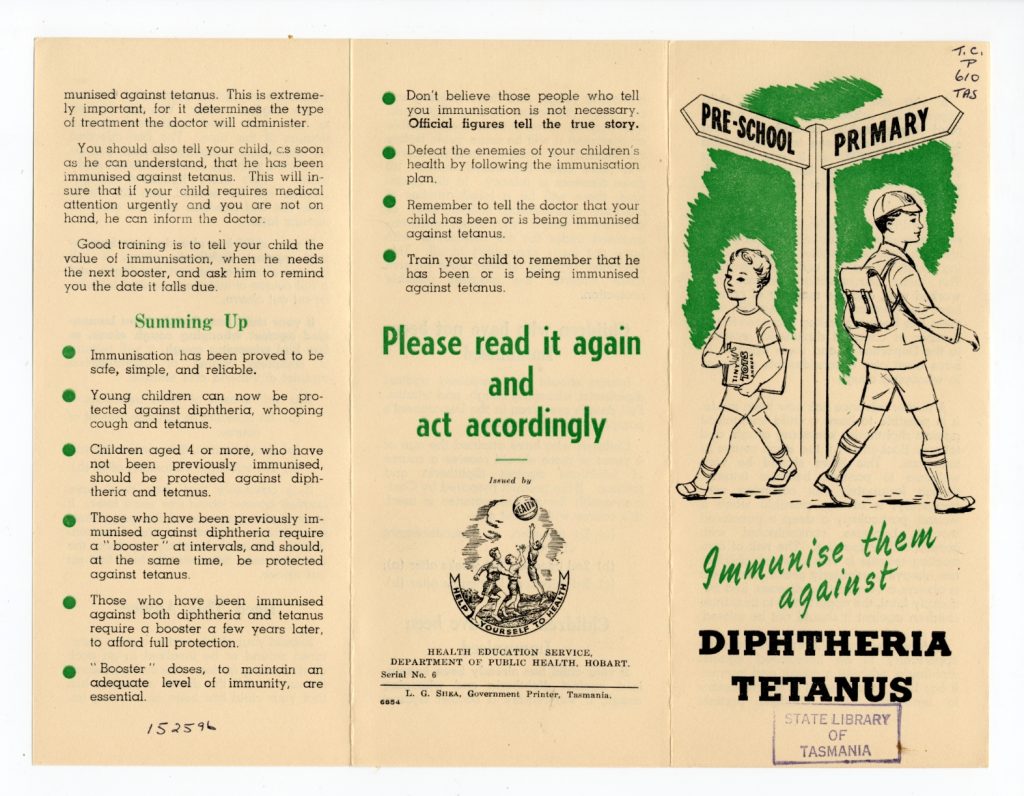

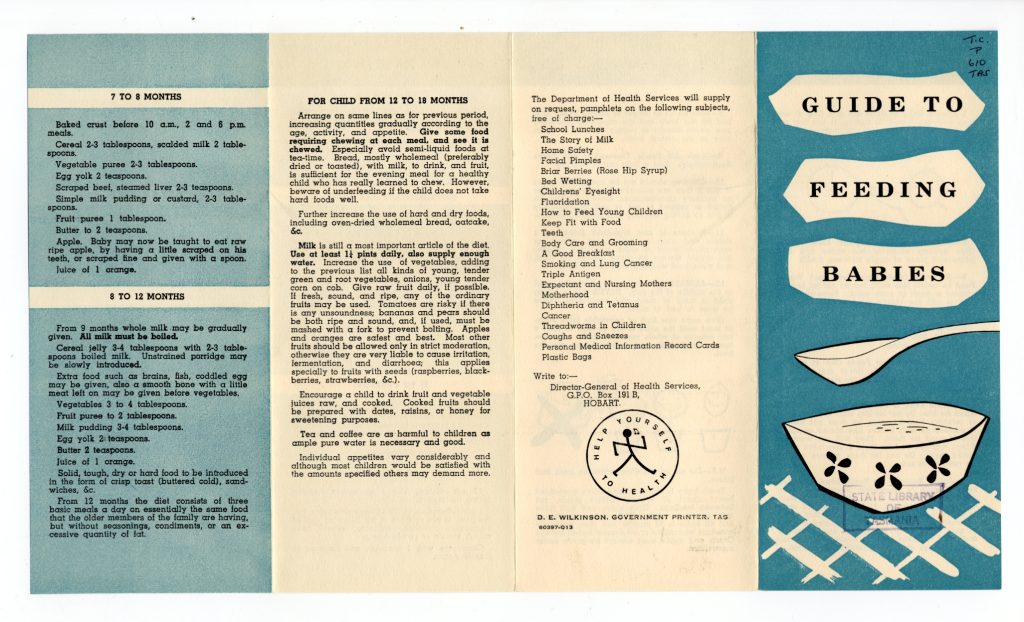

Shortly after this, a school nutrition officer was appointed. By means of pamphlets the nutrition officers, school nurses and dental nurses were able to provide advice to the parents. Pamphlets became the preferred way of communicating with the parents. We have a few of these pamphlets in our collection, and we’ve scanned a few examples – they make fascinating reading!

Guide-to-Feeding-Babies (PDF, 638 KB)

Diphtheria-Tetanus (PDF, 420 KB)

Writing in the Educational Record in 1950, the Director of Health Dr C.L. Park reported on the achievements of the School Medical Service. He wrote,

“Child Welfare Clinics have made rickets a rare condition; immunisation has prevented diphtheria with its consequent harmful effects on a child’s heart; the Tuberculosis Clinic has sought out and treated debilitating lung diseases; and teachers and Sisters alike have raised a generation of parents, the majority of whom consider it a disgrace to send a child to school dirty. Nowadays, School Doctors find that dental defects, mild anaemia, poor posture and enlarged thyroid are the commonest type of defect.”

Dr. C.L. Park, Report in Educational Record. Hobart: Department of Education, 1950.

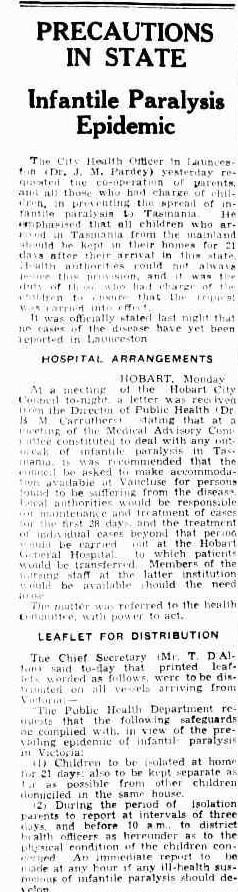

Schools and the Polio Epidemic of 1937-1938

Polio – or as it was also known, “infantile paralysis” – was a source of panic and terror before the “Salk” vaccine was developed in 1956. These days, polio has been nearly eradicated because of globally successful vaccination program, but before the vaccine was developed in 1956, schools were on the front line of epidemics. Tasmania in 1937 found itself in the grip of one of the worst epidemics in the world.

Polio is a debilitating and potentially deadly virus that strikes mainly children. It affects the brain and spinal cord and can permanently paralyze. For those fortunate children to escape with mild cases, “post-polio” syndrome can creep up on them years later.

In 1937, owing to an outbreak of infantile paralysis in the Victorian schools, school children moving from Victoria were required undergo a three week exclusion period for the Tasmanian schools to prevent the spread of the disease, then active in Victoria.

It was initially thought that Tasmania’s isolation and a few precautions would be adequate to protect the local children. But a few months later the epidemic struck Tasmania, and it struck hard. When it came it was so severe that it was amongst the worst in the world. While no definitive reasons for this were given it was thought that the poorer health in impoverished Tasmania didn’t help. Tasmania had been slower to recover from the depression than the mainland states. But the disease did not only afflict the poor. Children from the wealthier families were also affected.

There was no vaccination against the virus until 1956 so the only action the schools could take was to exclude the sick children and to be vigilant for signs of it in any children. Precautions were to be taken by the teachers and any cases were to be immediately notified to the department. The Christmas break in 1938 was the longest in 12 years, and communities like Cygnet banded together to donate fruit, picture books, and toys to polio-stricken children at the Hobart General Hospital.

Free School Milk!

Epidemic diseases like polio weren’t the only public health problems facing Tasmanian children. Endemic problems like poor nutrition and iodine deficiency also took a toll on young and old alike, and public schools were on the front lines here as well. The two programs etched in most people’s memories seem to be the free milk scheme and iodine tablets – and here’s a bit of their history.

The first free milk scheme came about originally to dispose of the leftovers from a Depression-era Christmas feast. In December 1930 the Casimaty Brothers, Hobart fish merchants and restaurateurs, gave the first of their Christmas dinners to the unemployed in Hobart. 400 meals were provided. The Christmas dinners ran successfully for four years but the Christmas of 1935 saw a decline in the number of people coming to the party. The Casimaty Brothers decided that the money they had been providing for the Christmas Party would be better used in providing free milk to the children in the schools. They invited other businesses to join them in sponsoring the free milk program.

At the time not all milk was pasteurised, and raw milk could be a carrier of TB. It was therefore vital that the milk to be delivered to the school children came from a herd that had been tested and declared to be tuberculosis-free.

The free milk program began in 1936. Children were to be provided with warm milk and straws, Cadbury’s had offered to donate cocoa to the schools so the children could have warm cocoa through the winter. But the milk was going to cost each child one penny. The penny cost was beyond the means of any parents, who may have several children at the school. So it was decided that those who could afford it would pay one penny and the school nurse would decide who was to get the free milk based on their nutritional needs.

In order to make the cocoa for the children, mothers needed to come to the school and heat the milk in billy cans over the wooden fires in the classrooms. They then distributed it to the children and stayed to clean and sterilise the bottles to be returned to the milk supplier. But the mothers had other children and duties to attend to and they quickly found they could not attend often. Soon the extra work fell to the teachers and it became an impossible extra burden in their already busy days. The teachers complained and this attempt at free milk lasted only for the one winter.

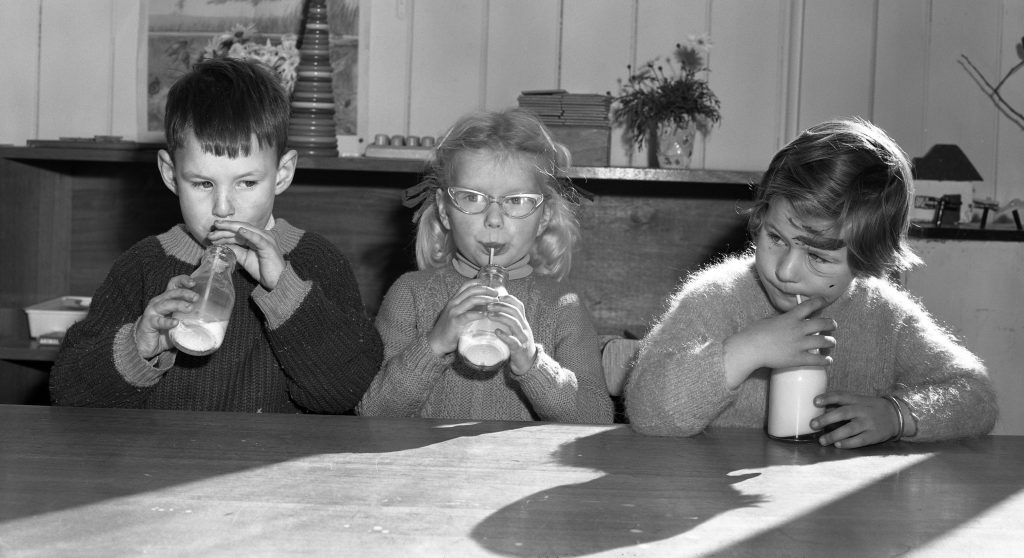

It wasn’t until the Commonwealth offered subsides to milk producers in 1950 (adopting a similar policy to that used in New Zealand since 1937), that the program was finally able to be implemented. The milk was received enthusiastically and the headlines the day after the introduction were , “Free Milk Issued: “Boy, It’s Good” : “Boy, It’s Good” was the general exclamation accompanied by much smacking of lips, when Launceston school children had their first taste of free milk yesterday” Primary school children on the West Coast received their free milk on a weekly basis with the milk being supplied from Hobart and Launceston.

The Film Unit of the Tasmania Education Department produced “Half a Pint of Milk” in 1952 . Apparently many city children did not know that milk came from cows.

There were many settling in issues including:

- Chipped and cracked milk bottles

- The milk tasted sour and had a bad odour

- The milk was left in a location where it could be contaminated by dogs (!)

- The bottles were not clean.

- Broken glass, sediment, and old milk bottle tops were found inside sealed bottles

- A number of children were reported as swallowing glass!!

- A large amount in dirt was discovered in samples taken from some milk suppliers.

- Some of the milk suppliers in the country districts reported it was uneconomical for them to have to provide pasteurised milk.

These problems were resolved and the milk program became a fixture of Tasmanian childhood. By 1965 the Department was reporting that more children than ever were drinking and enjoying their milk due to homogenised flavoured milk being available. The Minister reported in 1965 that the use of pasteurised milk had contributed enormously towards the control of tuberculosis and brucellosis, which had been prevalent in the early years of the twentieth century.

The school milk program finished at the end of the third term in 1973 having operated for 23 years – and because everyone seems to remember this so well – here’s a list of all our digitized pictures of kids drinking free school milk!

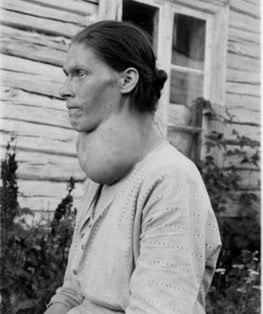

Goitre and Iodine Tablets, 1949

One of the most visible signs of undernourishment or poor nourishment in Tasmanian children was the prevalence of goitre, a condition caused by iodine deficiency. The whole of Tasmania was an endemic goitre area in the 1950s. A goitre causes a large and disfiguring swelling of the neck as the thyroid gland becomes inflamed. Other symptoms may emerge, such as extreme tiredness, dry itchy skin, increased sensitivity to cold, weight gain and poor concentration. If left untreated the condition resulted in swellings at the base of the neck that made swallowing difficult and could cause coughing and breathlessness. A surgical removal of the thyroid was a thyroidectomy that would result in a large scar across the neck, “where the second head was removed”. In the 1920s and 30 the mortality rate for the surgery was high and those with goitre avoided it, from both fear and the inconvenience of having to travel to Hobart for the surgery.

This condition was nearly ten times as likely to be found in females to males. The following comments were made in the Legislative Council debates in 1937,

“One had to only walk down the streets to see the large number of persons, particularly women, who were suffering from goitre.

And Dr Wilfred Crane reminisced in the Derwent Valley Gazette in the 1990s:

“Let me tell you of my childhood norms in the valley. Goitres … were common and huge, especially in older women. A goitre is a pendulous swelling at the front and side of the neck – they look like the barrel under the neck of a St Bernard dog. Goitres the size of footballs were common and it is remarkable that as children we took these disfigurements of older age as normal.”

Obviously children suffering from this condition would not do well at school when and if they were well enough to attend.

An iodine deficiency was known to be the cause of goitre, and by the late 1930s a number of overseas studies were using iodised salt. But it was felt that children did not and should not eat sufficient salt for this to be a successful preventative measure. It was therefore recommended that iodised tablets be given to the children up to the age of fourteen years. The practise of issuing weekly goitre tablets started in 1949. As any parent will know, giving children tablets didn’t mean they would swallow them. Some liked to add the tablets to their ink wells, as the potassium in the tablets changing the black blue ink to a purple colour. Some districts had more success with the treatment of goitre than other schools and this was regarded as a reflection on how seriously the teachers took the project. Many assigned the issuing of the tablets to student “goitre monitors” and few gave the children reasons why it was so important for them to take their pills. As many of the children lived in families were goitre was common it’s likely they were not afraid of it.

There were some concerns that the milk the children were being given at the same time as the iodine tablets were having a counter-productive effect, and this was the subject of many studies over the next decades, when it was eventually realised that the tablets didn’t work because the children either didn’t take them of took too many. By 1967 a decision had been made to add iodine to bread baked in Tasmania instead.

To read even more about iodine deficiency and endemic goitre in Tasmania, check out this great article by Erin Cooper and the ABC’s Curious Hobart team.

Further reading:

Explore 150 years of public education in Tasmania

Educational Record, Hobart, Education Department, 1905-1967

Report on the System of Primary Education in South Australia. Government Printer, Hobart, 1904.

Medical examination of state school children 1906 J. S. Elkington, Hobart, Government Printer, 1906

Goitre monitor: the history of Iodine Deficiency in Tasmania, Paul A.C. Richards & John C. Stewart, Myola, House of Publishing, 2003

Health Reader by J.S.C. Elkington, Christchurch, Whitcombe and Tombs Limited, 1907

The Great Scourge: the Tasmanian Infantile Paralysis Epidemic 1937-1938, Anne Killalea, Artemis Publishing, Hobart, 1995

Health in the School, J.S.C. Elkington, Blackie and Son Limited, London, 1907

The Trials of W. L. Neale, by D.V. Selth, Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania, Volume 104, 1969

Tasmanian Archival resources:

HSD6/3/621 – 622 MILK Ministerial – Public Health – School Medical service –

Milk in Schools – Correspondence

HSD5/1/4106 – 22/400 School Medical Service – Administration – school milk

HSD5/1/1897 – 22/402 – Child Health – School Medical Scholl Milk – complaints

AD9/3/63 – 2/7G (1) Free school milk scheme

ED10/1/1387 Hot Milk – Supply to all Schools

ED10/1/1155 Casimaty Fund – supply of milk to school children

Does anyone have information about E. S. Anthony who ran a pipe and hardware importing business in Hobart in the 1890s known as E. A. Anthony and Co.?

Hi Joan, it would be worth sending your question to our research service. Just submit this form and a researcher will get back to you within 20 working days: https://sltas.altarama.com/reft100.aspx?key=Research

This is pure history, really amazing!

I recall watching several TV shows in the 80’s or 90’s about Free School milk in the 50’s or 60’s having stuff added to it that was causing growth problems in children and then later their own children were being born with defects, like messed up limbs or limbs missing entirely among other issues and it was all traced back to the milk being the cause and I think it was stated it was one of the primary reasons free school milk programs were dropped.

Oddly enough I can find nothing online about it, and every article I come across like this fails to mention it also. Believe it was an issue specifically tied to Tasmanian school milk.

Is Tasmanian or Australian history being white washed?

I’ve spoken to other people and they also recall this happened or they saw these programs where they interviewed the kids grown up and also their offspring.

What is going on? I don’t believe in the Mandella Effect.

A very interesting article – lots of research! I remember goitre tablets and milk at South Hobart Primary School in the 1960’s.