Filtered through the Factory Part Two: Sarah Birmingham

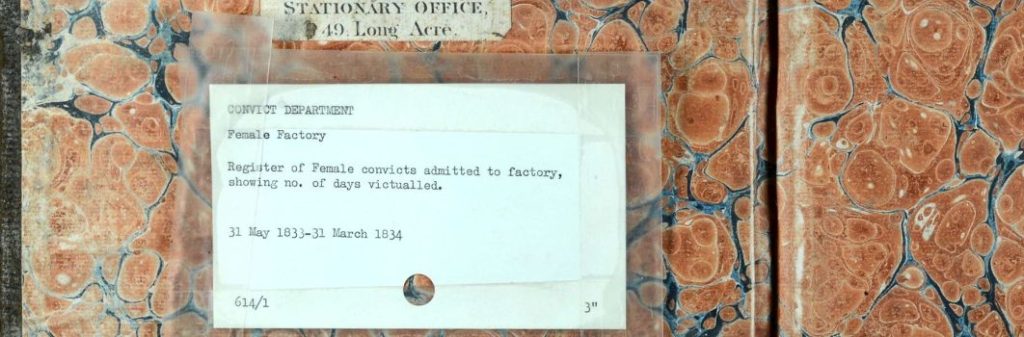

In part one of this blog, we looked at the Cascades Female Factory admission register (Female House of Correction, Hobart – Register of Female Convicts admitted to the Factory, showing Number of Days Victualled, Tasmanian Archives: CON139/1/1), which records female convicts who passed through the ‘Female Factory’ from June 1833 to March 1834. This record tells us where the women were coming from (their assigned employer, police office or other institution), how long they were held in the Factory and where, or to whom, they were sent. You can search the data from CON139 in the Tasmanian Names Index.

This time, we are looking at a female convict who had a child in the institution.

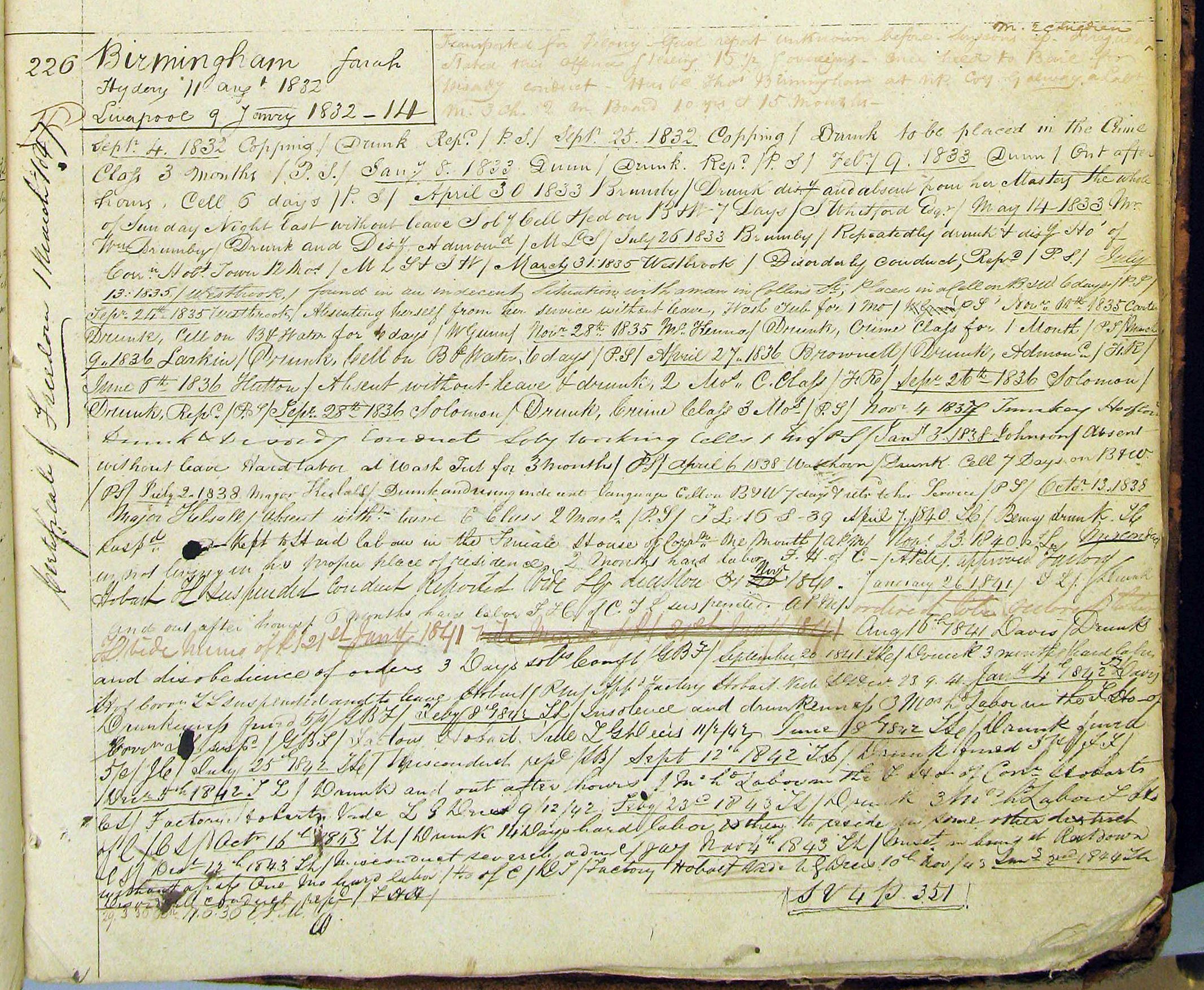

Sarah Birmingham was a 31-year-old Catholic woman from Galway, Ireland. She came to Van Diemen’s Land on the Hydery in August of 1832, on a 14 year sentence for stealing money. She was married and had two children who came with her on the ship: a ten-year-old, and fifteen-month-old James. Sarah was consistently in trouble throughout her sentence, starting with a reprimand for being drunk barely one month after her arrival. The next charge of being drunk sent her to the Crime Class of the Factory for three months (women in the Crime Class were to perform hard labour) (Female Convict Research Centre, 2012).

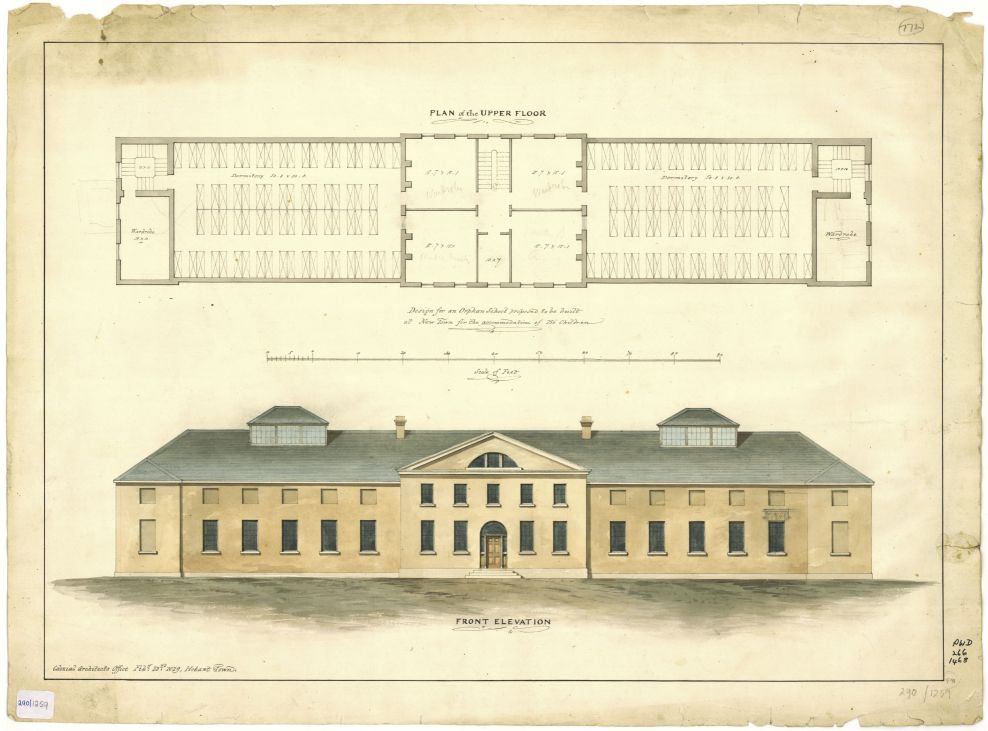

The Cascades Female Factory admission register records the presence of children in the Factory. Children born to convict women typically spent the first months of life in the Factory with their mothers, but after being weaned they were put in the charge of other convicts in the nursery until they were old enough to be sent to the Orphan Schools at the age of three (Tasmanian Archives: CSO1-1-902 file 19161 p.1123-126). Many died. The years covered by this register were actually the worst years, with a death rate of around 40% of children (Brown, 1972). Convict women would be kept in the Crime Class of the Factory for 6 months after being removed from their child and then returned to assigned work. Often they would be grieving the death of a child or worrying for their welfare. Sometimes their work would involve caring for the children of colonists, while their own children were being kept in the Factory in dire conditions (Frost, 2004). Compared with the convicts themselves, information about the lives of convicts’ children is scarce. Any small detail that can be the clue that pinpoints them in a place and time.

Effectively orphaned on arrival

If Sarah kept in touch with her ten-year-old child, we do not have record of it. They are not named in she convict records, and do not appear in the Orphan School records. I also could not find any records for the surname that match up with their projected age. The alternative being life in an institution, they may have sought out work or an apprenticeship and established some kind of independent life. They may have assumed a new name to avoid association with their convict mother.

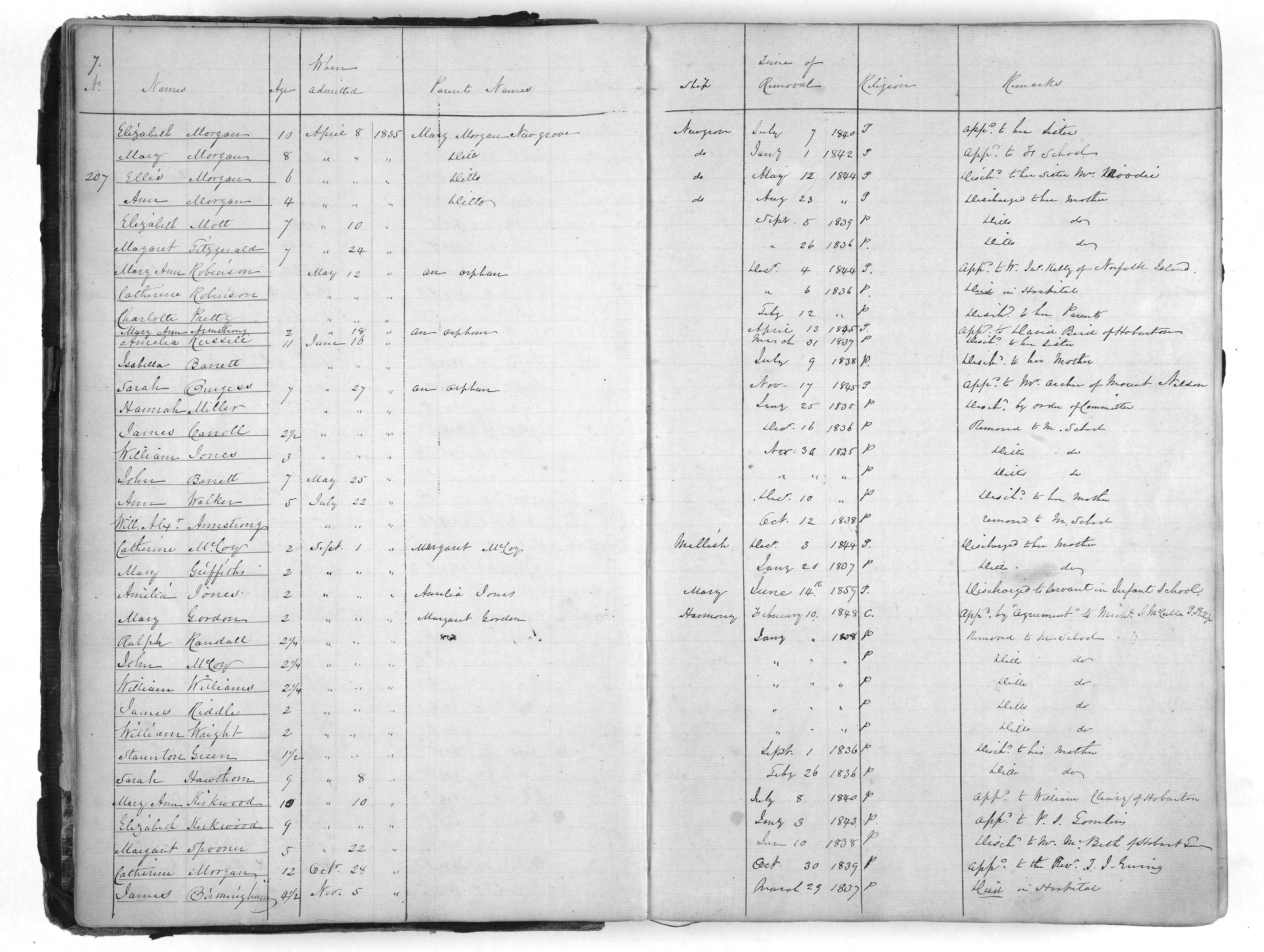

Sarah’s younger child, James, was still an infant. I spent some time trying to establish where James would have stayed before his first appearance in the Female Factory register in July. The register shows that he was there every day of July, which suggests that he either arrived on the first day of the month, or that he was already there. There is a page missing from the June returns, in the section which records the children. His was probably one of the names on that missing page, which would mean that James was kept in the Factory’s nursery yard from their arrival in January 1832 until he was discharged to the Orphan School on 9th of September 1834 (Tasmanian Archives: SWD28/1/1). Sarah was not in the Factory for much of that time, but arrived back there in December 1833, coming off the government Brig Tamar, which was used for transporting goods and convicts around Van Diemen’s Land.

While some women may have been able to persuade their employers to let them keep their children with them when assigned to work, it does not seem to have been a common practice. The employer would have to be willing to feed and house the child. The mother would have to trust that the child would be safe, and not used as a way to control her.

Whether by choice or by force, Sarah did not take her child with her.

Service in the North

From at least April of 1833, Sarah was in the service of one William Brumby (Tasmanian Archives: CON40/1/1). Brumby was a farmer and publican, licensing the Crown Inn in Norfolk Plains in 1827 (Colonial Times and Tasmanian Advertiser 19/10/1827). William Brumby’s father was James Brumby, a Sergeant in the New South Wales Corps and had established a punt ‘at the junction of the South Esk and Lake River’. He was granted land along the river in 1824 for this service (Tasmanian Archives: RGD32/1/1/ no 215; CSO1/1/44 file 831). William Brumby participated in the ‘operations against the aborigines’ from October to December 1830, and provided supplies to the roving parties (Tasmanian Archives: CSO1/1/710 file 15538). William was 36 when he died in 1841 of ‘decline’ (Tasmanian Archives: RGD35/1/16 no 520). His wife, Ann, was listed as the head of the household on the census in 1842 (Tasmanian Archives: CEN1/1/30).

William brought Sarah before the magistrate in April and May of 1833 for being ‘drunk and disorderly’ and absent from her master’s house ‘the whole of Sunday night’. The first time she was sent to ‘solitary confinement for 7 days and fed on bread and water’, the second time she was ‘admonished’. The final straw came on 26 July when she was given 12 months in the ‘Female House of Correction’ for repeating the offence. It seems that Sarah Birmingham was put on the Tamar to travel from Norfolk Plains back to Cascades to serve her punishment. It is unclear what happened in the 6 months between her sentence and her arrival in Hobart. Perhaps she was waiting around for a suitable transport to arrive.

Return to Cascades

If Sarah and baby James were reunited upon her return, it was only briefly. Sarah was only at Cascades for a couple of months before being sent to the hospital in February of 1834. We have no records from the hospital for this period, so we don’t know how long she was there, or for what purpose. The register ends in March, and does not state her return to Cascades, but her period of punishment shouldn’t have been up until at least July of 1834 (Tasmanian Archives: CON40/1/1).

The next thing we hear about is Sarah being reprimanded for ‘disorderly conduct’ in March 1835, while in the charge of ‘Westbrook’. This could have been the Doctor, J.H Westbrook, in which case she may have been assigned to work at the hospital rather than being sent there for an illness. She was still working for Westbrook in July when she was ‘found in an indecent situation with a man in Collins St’ (she spent 6 days in a cell on bread and water for this). Westbrook gave her one more chance, but less than two months later she was absent without leave and sent to the wash tub for a month.

Life and death

Sarah was in a relatively quiet period between punishments for drunkenness and absences during the time period when James is recorded to have ‘died in hospital’ on 29 March 1837. His death is recorded in the orphan school register, but not in the civil registration books. He was four and a half. We have no way of knowing whether his mother was informed of his illness, or allowed to see him before he died.

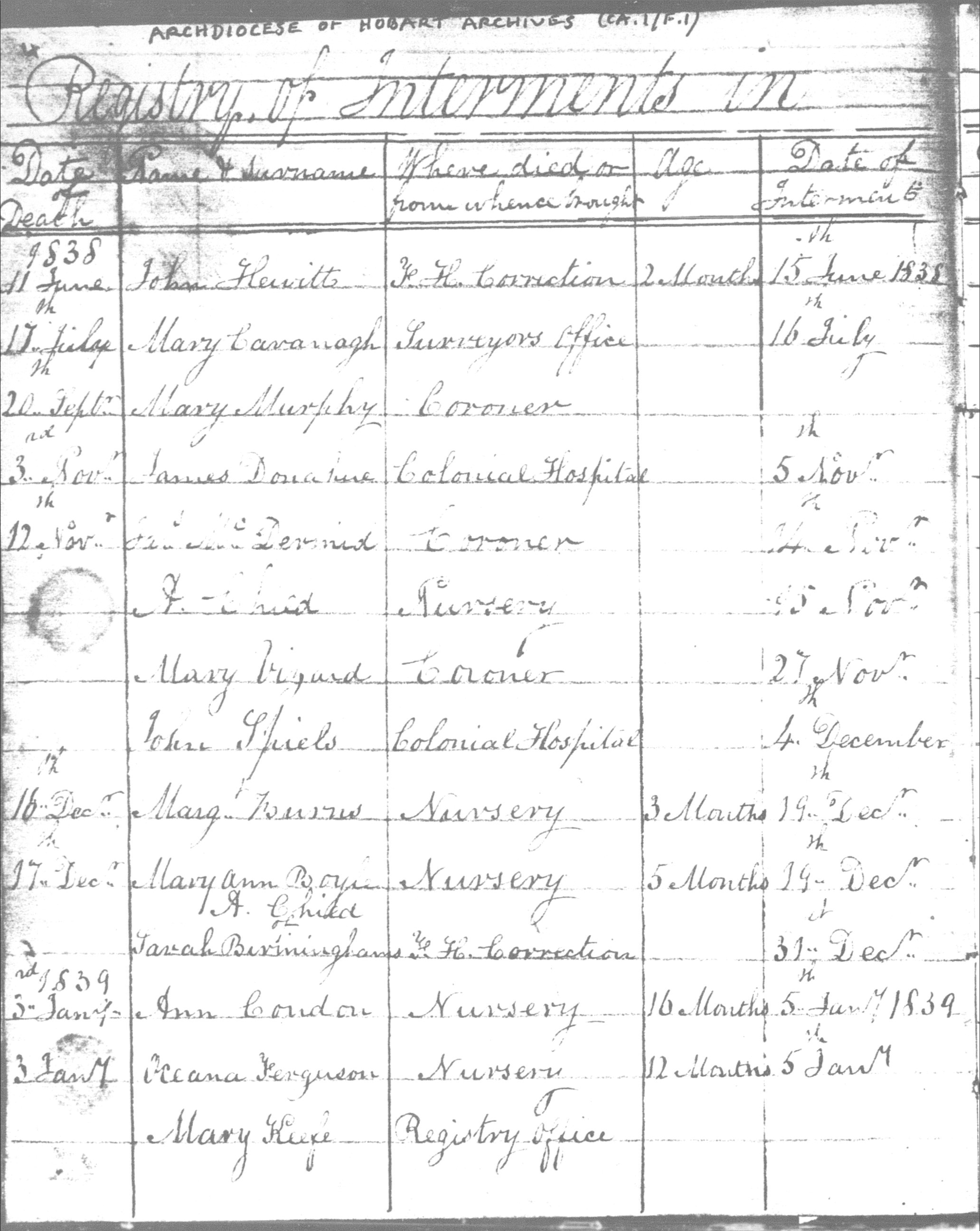

Sarah continued to be repeatedly drunk, disorderly and absent. It was about April 1838 (drunk, cells on bread and water for a week) that she became pregnant. At about 4 months pregnant she was drunk and using indecent language (placed in the cells on bread and water, then returned to her assigned service). At 7 months pregnant she was found to be absent without leave, (imprisoned in the crime class yard for 2 months). The child was buried in December 1838. Again, there was no civil registration record, so its birth and death have been assumed from the record of burial. This may have been because the Catholic records were kept separately, and not as systematically copied when civil registration became compulsory in 1839.

Ticket to nowhere

In 1839 Sarah obtained her ticket of leave. She held her ticket for 8 months before having it suspended due to drunkenness.

In October of 1843 Sarah was sentenced to ’14 days hard labour and then to reside in some other district’. We know that this ‘other district’ was somewhere on the Eastern shore of the Derwent because in November of 1843 she was in trouble for being at ‘Restdown’ (a property in Otago) without a pass. This brought her back to Cascades for a time.

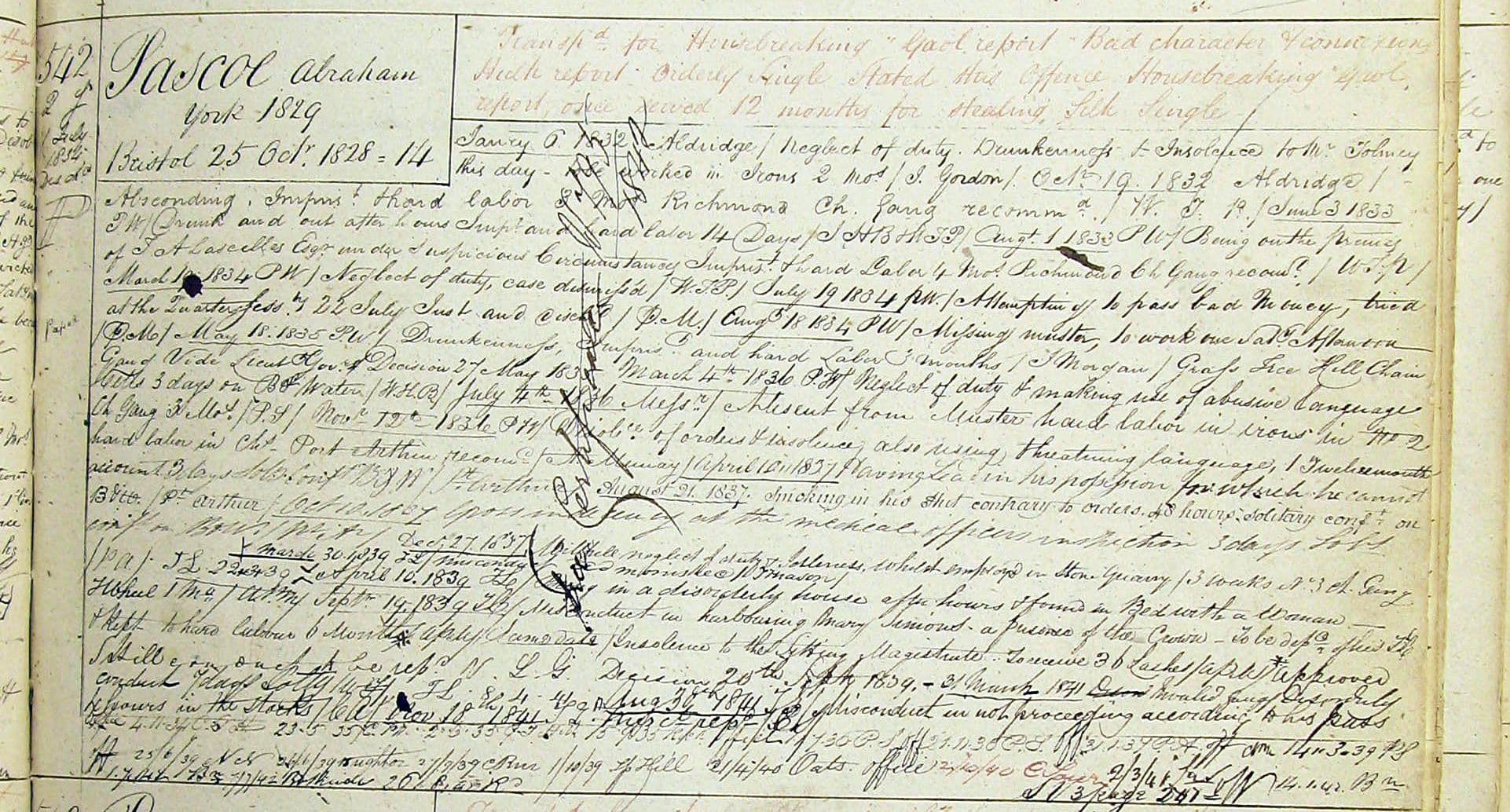

In 1842 a fellow convict named Abraham Pascoe applied to marry Sarah. The entry in the marriage permissions register reads ‘not approved – the woman. Not deserving’ (Tasmanian Archives: CON52/1/2). This seems hardly fair, considering his conduct record is just as packed with offences as hers.

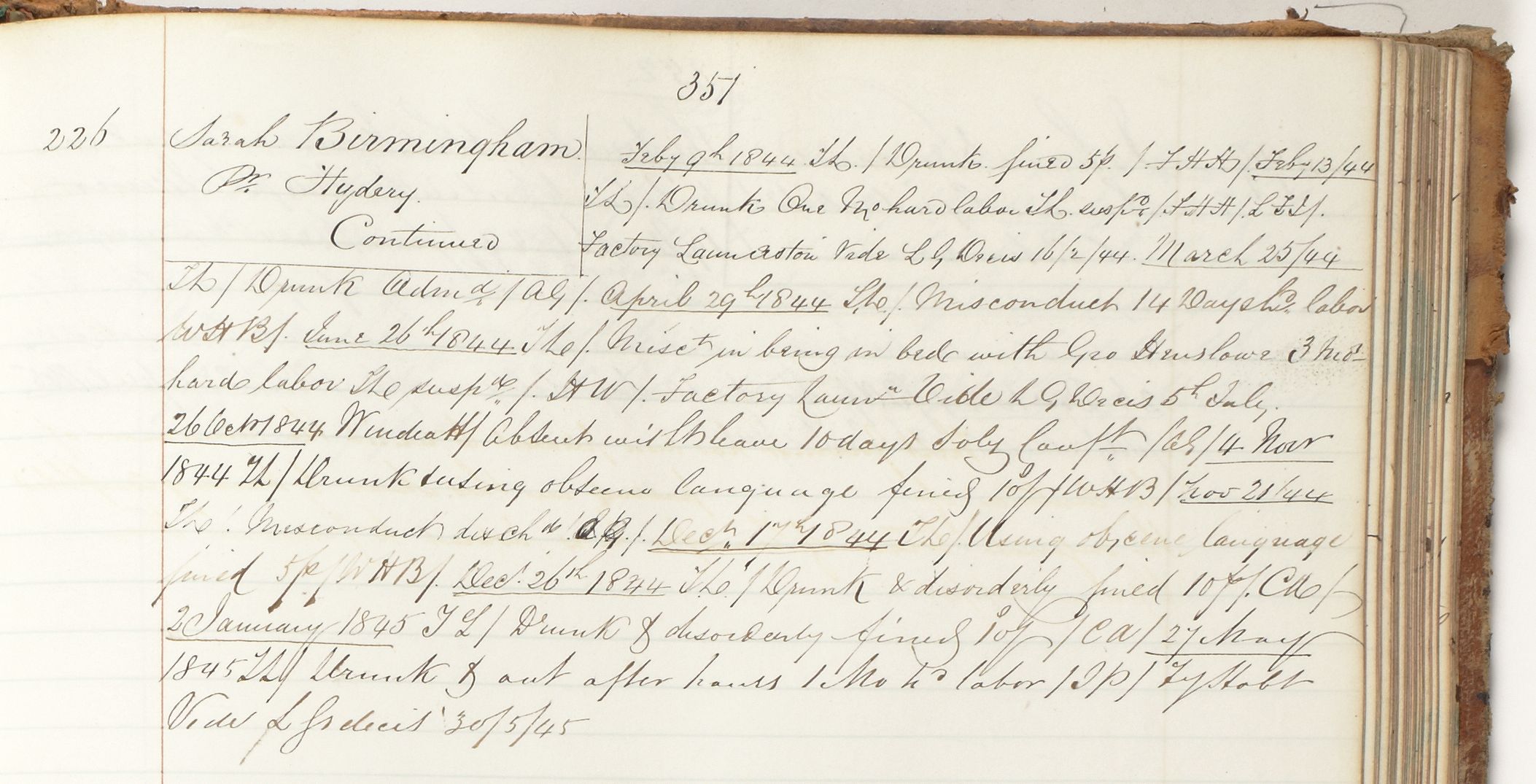

Early in 1844 Sarah Birmingham was in Launceston, where she found herself in and out of the Launceston Female Factory, and again suffered temporary suspensions of her ticket of leave – once for being drunk, and again when she was found ‘in bed with George Henslowe’ (Tasmanian Archives CON32/1/4). The only information I can find on George Henslow was a police report from Launceston in 1842 in which he was fined 10s for ‘riding on his cart (Launceston Examiner 2 Jul 1842). It was a safety violation to ride on a cart without reins (The Tasmanian Colonist 28 Aug 1854).

The offences continued, practically monthly. Absent without leave (10 days solitary confinement), drunk and using obscene language (fined), drunk and disorderly (fined), drunk and out after hours (1 month hard labour). Sarah was obviously an alcoholic, and pursued her addiction regardless of the cost.

Sarah spent some time in Longford in 1844, according to the location of the charging magistrate (Female Convict Research Centre). In 1845 she returned to the Female Factory in Hobart.

Freedom in obscurity

Sarah finally obtained a Certificate of Freedom in March 1847. From there, her trail goes cold. Perhaps the record of her death, like those of her children, is somewhere within the Catholic archives. Perhaps she changed her name. After living 14 years under the close scrutiny of masters and enduring harsh punishments every time she had a few drinks, it must have come as a great relief to have some choice returned to her life.

Convict women found themselves returning to the Female Factory over and over again. It was the place they arrived, where they gave birth, where they were separated from their babies, where their babies died, where they suffered punishments. It may have also been a place of community and solidarity, but mostly it was a site of trauma.

References

Brown, Joan C., 1972, “Poverty is Not a Crime”: Social Services in Tasmania in 1803-1900, Hobart, Tasmanian Historical Research Association.

Female Convicts Research Centre, 2012, Convict lives : women at Cascades Female Factory, Hobart : Convict Women’s Press.

Frost, Lucy, Footsteps and voices : a historical look into the Cascades Female Factory, Female Factory Historic Site, 2004.