An International Woman: Emily Dobson (nee Lempriere)

Community Archives recently purchased a studio portrait of Emily Dobson (nee Lempriere) (1842-1934) as a young woman. It provides a rare window on the early life of a woman who entered the public sphere in her 50’s and was a prominent activist until her death at 91.

Emily Dobson was a wealthy, nineteenth-century woman who used her position in society to organise and influence her community into action. Mrs Dobson is known for creating, and being the driving force in at least nineteen philanthropic societies. She was endlessly curious and had a wide range of interests that evolved throughout her life. Her interests ranged from alleviating poverty through health, sanitation, food and housing, and caring for the needs of the sick and people with disabilities, through to social and educational organisations for women and girls, such as the Girl Guides, Victoria League, Alliance Francaise and Lyceum Club. Although Emily did not agitate politically or challenge the establishment, she worked hard to improve society in the ways she felt were proper.

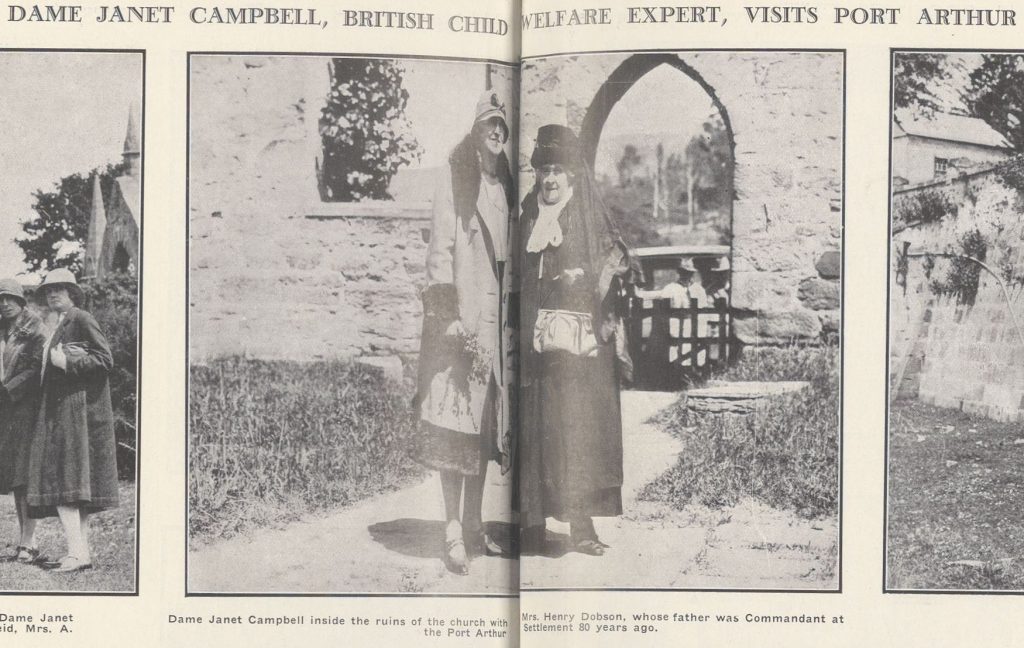

Emily Lempriere was born in 1842, the eleventh of twelve children born to Thomas James Lempriere and Charlotte Smith. Although her birth was registered in Hobart, when interviewed by a newspaper for her 90th birthday, she told them that she was born at Port Arthur “outside the stockade” (The Mercury, 10/10/1932). Her father was, at that time, the Deputy Assistant Commissary General. Emily had no formal schooling, but both of her parents were educated and she was ‘educated at home’ (The Mercury, 6/6/1934). Her mother Charlotte and her aunt Harriett had opened a school for young ladies in 1825, and her father is reported to have taught her older siblings (Jordan, 2004, p.29). Emily’s father died in 1852, after becoming ill during an appointment to Hong Kong. After this, it is thought that Emily went to live with her eldest brother (Jordan, 2004, p.28). Previous studies of Emily’s life had not discovered when her mother died. However, improved indexing of newspapers and registration records has allowed me to establish that Charlotte Lempriere lived until 1890, when she died in Bellerive, aged 87 (The Mercury, 29/9/1890, RGD35/1/59 no 542). It is therefore possible that her mother was able to continue her youngest daughter’s education herself. Emily certainly seems to have developed an enquiring mind.

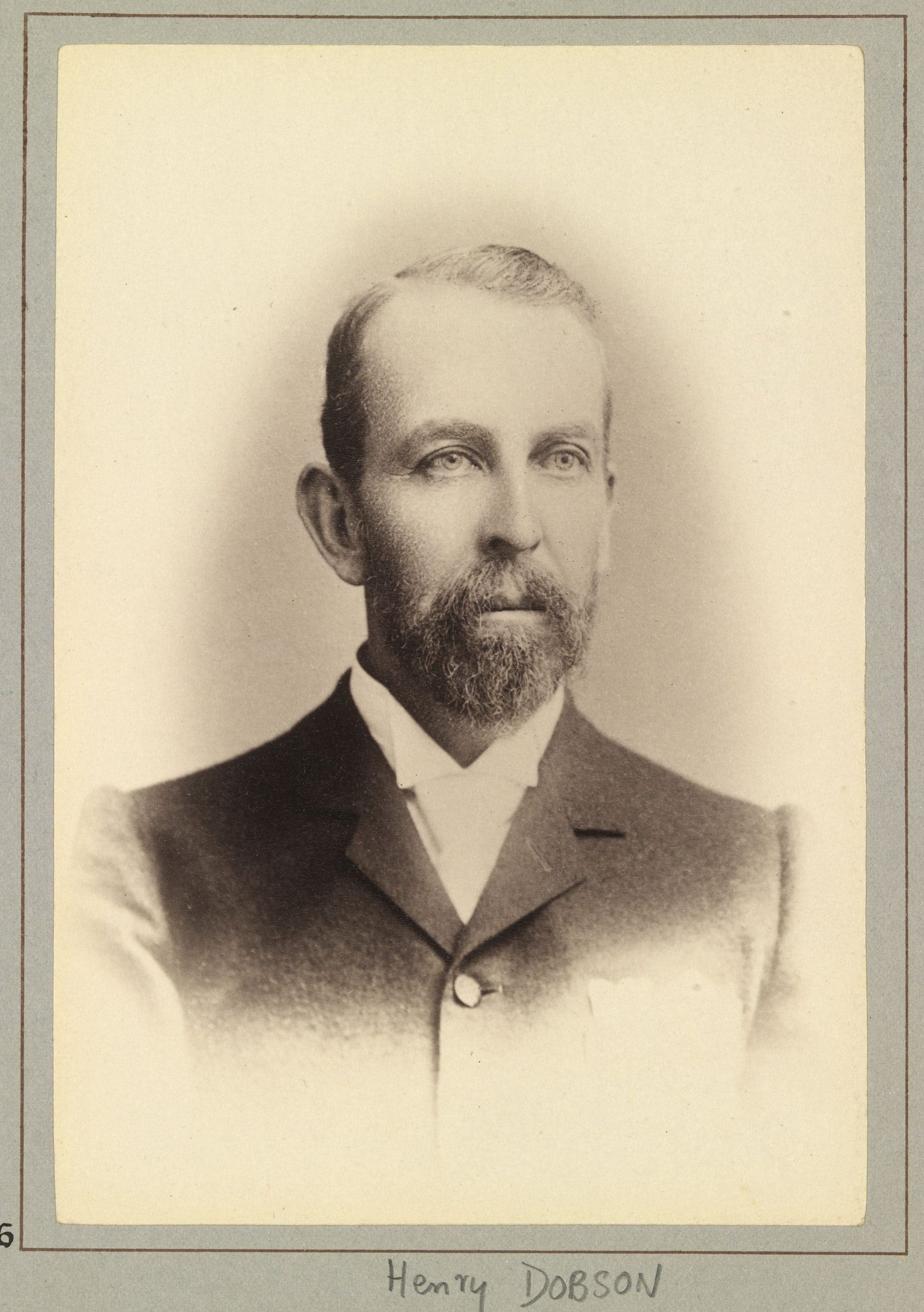

Emily married Lawyer Henry Dobson (later Tasmanian Premier) in 1868. This was an advantageous marriage. Henry was a successful lawyer from a family of successful lawyers, and had considerable means. He was elected to the State House of Assembly in 1891 and was Premier from 1892-1894. He was Tasmania’s representative at Australia’s Federation convention and a federal senator from 1901-1910. He was also a man with an active interest in social causes, as well as music, literature and sport (Dollery, 1981). The Dobsons lived at 1 Elboden Place in South Hobart, known as ‘Elboden House’ (Valuation and Assessment rolls, 1899). This was a very fashionable address, among others of their social class, such as the Allports.

After raising a family of 6 children, Emily took to public life in the 1890s, around the same time as her husband ran for public office. One gets the sense that Emily came across an issue – perhaps discussed it with her husband – and very seriously considered the question ‘what can I do?’ Although she did not seek to challenge or overstep the boundaries of what was proper for a woman to do in the public sphere in her era, Emily took what action she could.

The first issue Emily and her friends tackled was sanitation in Hobart, in response to a typhoid outbreak in 1891 (Taylor, 1973). They established a Women’s Sanitary Association which discussed the problems of drainage and sewerage removal, assembled petitions to council and went door-to-door educating households about health and hygiene (Tasmanian Mail, 12/9/1891, p.6, 3/10/1891, p.32). As with many of the organisations Emily was part of, it is hard to say how much of an impact they had. At the least, their activities helped to keep the need for better drainage and waste disposal systems in the public conversation.

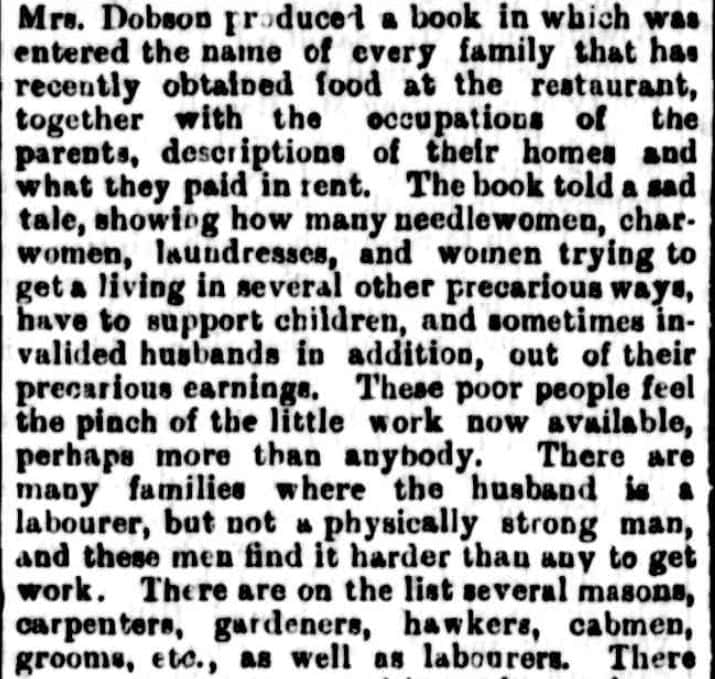

The next endeavour was to set up a soup kitchen to alleviate hunger during the depression of the 1890s (Tasmanian News, 9/6/1893). In the winter of 1893, Emily led a team organising for the delivery of donated meat, vegetables and bread, cooking and serving soup to an average of 700 people a day (The Mercury, 28/10/1893). From the beginning, Emily could be found ‘in a large white apron and sleeves…taking the tickets’ at the door (Tasmanian Mail 24/6/1893). Recipients paid a penny, so that their pride would not be injured by resorting to charity. The kitchen operated from June to October of 1893, and might have continued if they had received enough funding to remain solvent.

It seems that as part of the operations of the soup kitchen, the ladies collected data on the recipients of the meals. Emily showed this information to The Mercury reporter who documented the closure of the kitchen in October 1893. By drawing attention to the number of working-class women who were attempting to support whole families doing low-paying insecure work, this brought the lives of women and the economic importance of women’s work into the public conversation. Close proximity to the poor might have also increased Emily’s awareness of the housing crisis among the poor.

The problem of sub-standard housing was a logical next step from Emily’s concerns about sanitation and poverty. A committee of ladies decided to set up a company that would build affordable, adequate housing for the poor, with funds raised by selling shares to businessmen (Jordan, 2004, p.32). The scheme did not gain much traction, and the Dobson’s attentions were soon drawn to a new idea.

One of the most interesting schemes that Emily and Henry Dobson threw their energy behind was the Village Settlement Scheme. What started as an interest in alleviating the crisis of substandard housing in Tasmania was, unfortunately, diverted by a wave of enthusiasm for land settlement schemes. The idea that the poor could work themselves out of economic depression if they only had a few acres of land to farm was one that continued to entice policy-makers for many years, and resulted in Soldier Settlement Schemes around Australia after the First World War. There was also a prevailing idea that Tasmanian’s over-reliance on government employment and over-concentration of workers in the cities had contributed to the depression (Bolger, 1965, p.102). As such, the original idea for a corporation to build affordable housing that was cooked up by Emily and her friends was not as compelling as it might have been in different times. It may also be significant that Henry was Premier at this time, and Emily may have been strongly motivated to support his choice of project at such a critical time in his political career. Henry resigned as Premier after the 1894 dissolution election returned none of his supporters (Dollery, 1981).

The Tasmanian Village Settlement Scheme of 1894 aimed to take a group of unemployed men and their families to Southport and attempt to establish a co-operative village. Funds were raised to provision the settlers for their first years and rules were drawn up to establish the conditions for the eventual granting of 25 acres to any family that met them. Emily herself accompanied the settlers for their first week on the land in November, sleeping ‘under canvas’, but had returned a couple of days before wild winds blew all of the tents down (Mercury, 10/11/1894). Emily also personally visited the settlement in late December, checking up on how the settlers had spent their Christmas (Mercury, 3/1/1895) . In both of her reports she was optimistic, considering the families who chose to abandon the settlement as ‘unsuited’ for the venture (Mercury, 6/11/1894). Unfortunately, Emily’s optimism and positivity could not gloss over the devastation of bushfire which destroyed the one co-operatively built hut and all the logs prepared for splitting in early 1895 (Bolger, 1965, p 111). With little to show for their efforts, the Village Settlement Committee returned the land to the government in 1898.

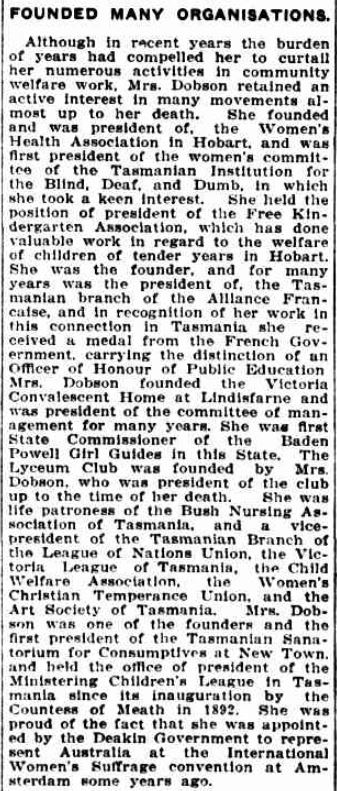

By the time the Village Settlement project came to a close, Emily had acquired a taste for working in philanthropic societies. She went on to found a wide range of organisations, often inspired by the activities of some of her international contacts. This section of her obituary gives an extensive list.

The sheer volume of Emily’s activities is exhausting to think about. This article from Labor newspaper The Clipper satirises her work.

As the wife of a conservative politician, Emily was often sent up by The Clipper, as well as other newspapers from time to time. The Clipper in particular charged her and her committee ladies with hypocrisy and essentially playing with the lives of the poor and working classes, suggesting in scorn that they ‘merly [sic] want to pose as philanthropists and to have power that patronage gives.’ (The Clipper 10/6/1893, 17/6/1893, 30/9/1893). The Clipper‘s criticisms of Emily Dobson and her committees appear to have been mostly politically motivated – the frustration of a labour movement who felt their goals to create jobs and develop government social support structures were being stymied by social support for charity efforts. It should also be noted that these criticisms came at the beginning of Emily Dobson’s philanthropic efforts. In retrospect, it is much harder to minimise her nearly 40 years of activities in public life as mere play.

If they had been working on the same side, it seems likely that Emily and The Clipper would have found some common ground. The efforts of the charitable bodies she worked for were often curtailed by a lack of sustained support, which would have only been possible through government funding. One example is the effort to establish an industrial school for the blind. Emily was president of the ladies’ committee of the Blind, Deaf and Dumb Society and the associated Braille Society. The society lobbied the Chief Secretary to support the school, but although it secured the donation of a building, there was to be no continued government support for its operations (Tasmanian Mail 13/8/1895, 22/2/1899,). This left the consistent funding for the school up to public support, which had to be regularly drummed up through the agitations and creativity of someone like Emily.

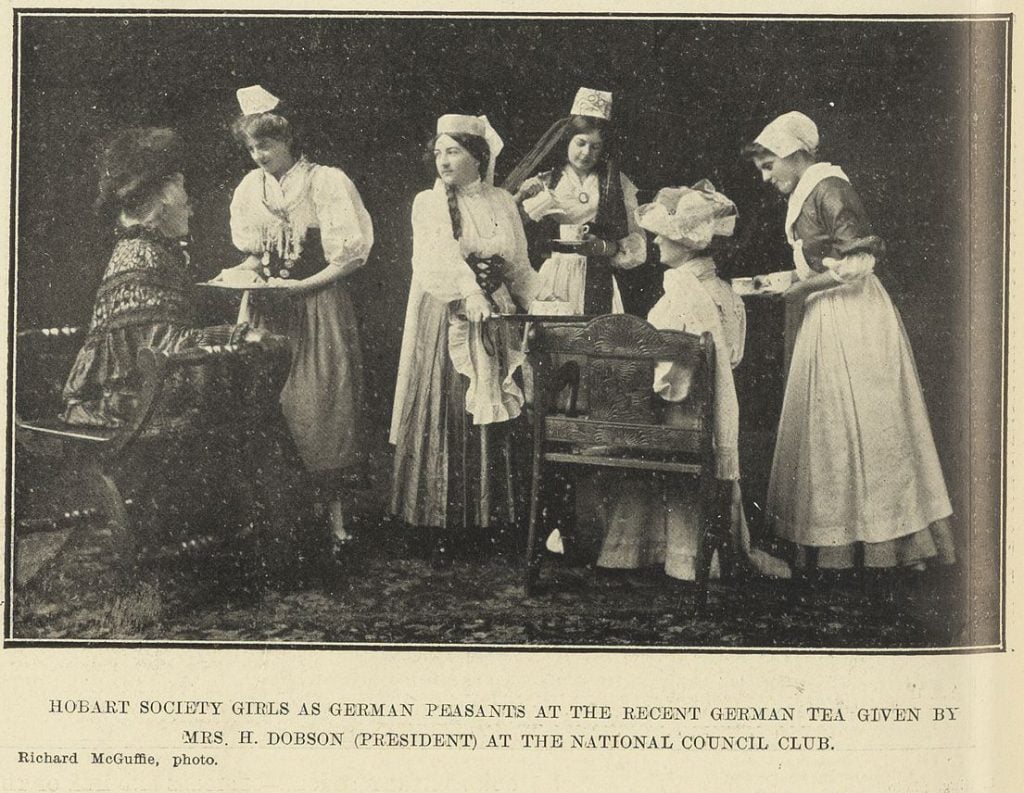

However, it can’t be denied that, in the midst of her more serious pursuits, Emily Dobson had a lot of fun with her philanthropy. Her fundraising events included fetes, dinners and parties, an annual strawberry feast, and even theatrical productions (Taylor, 1973, pp. 75-77). For example, in 1892 she ‘got up’ a night of theatre to benefit ‘two French ladies, who have been in Hobart for some time, and who have suffered severe losses by the hurricane in Mauritius’ (Tasmanian Mail 1/10/1892). Not only did Emily organise the variety show, she played the role of the villain in it’s main piece – ‘a bright, sparkling little French operetta’. She clearly enjoyed the spotlight. It seems that her performances were well-known to the society audiences, and there are reports of her personal theatrics at a number of the fundraising events she organised and hosted.

Emily seems to have hardly had friends over for tea without it being a meeting of a committee, or hosted a gathering that wasn’t in aid of a cause. Considering her conservatism, this would not have been possible without the approval of her husband. Henry’s interest in similar causes, his money and willingness to accommodate events and visitors in their house, and to facilitate his wife’s regular travel all facilitated her lifestyle and activism. Emily supported her husband in his endeavours, such as the Free Kindergarten Association which they began together in 1911 (Reynolds, 1981). But she also seems to have operated with considerable autonomy. The name ‘Mrs Henry Dobson’ appears often in the Australian newspapers, marking her activities and her travel to different parts of Australia or the world, with rarely a mention of the man himself.

Emily and Henry often worked alongside each other – he would be a speaker at meetings of her organisations and donate to her causes, and she would canvas for his political campaigns. However, it seems that Emily’s actions and opinions on issues were her own – influenced by her curiosity and engagement with the broad range of ideas available to her through wide reading, attendance of lectures and, of course, meeting and discussing issues with other women around the world.

With Emily Dobson’s zeal for organising, it is little wonder that she took up the opportunity to get involved in the National Council of Women in Tasmania (NCWT), a branch of the worldwide organisation that met every 5 years as the International Council of Women (ICW) (Jordan, 2004, p.22). The ICW president had written to every colony in the British Empire to encourage the formation of National Women’s Councils, and the Tasmanian branch was formed in 1899. Each council was composed of representatives from women’s organisations and charities. Emily became one of the three delegates to the first ICW congress of August 1899, along with the President and Vice-President of the NCWT, who were the wife of the governor (Viscountess Gormanston) and a former governor (Lady Teresa Hamilton), respectively (Jordan, p.23). It was Mrs Dobson’s notes on the congress that were printed in The Mercury (5/9/1899).

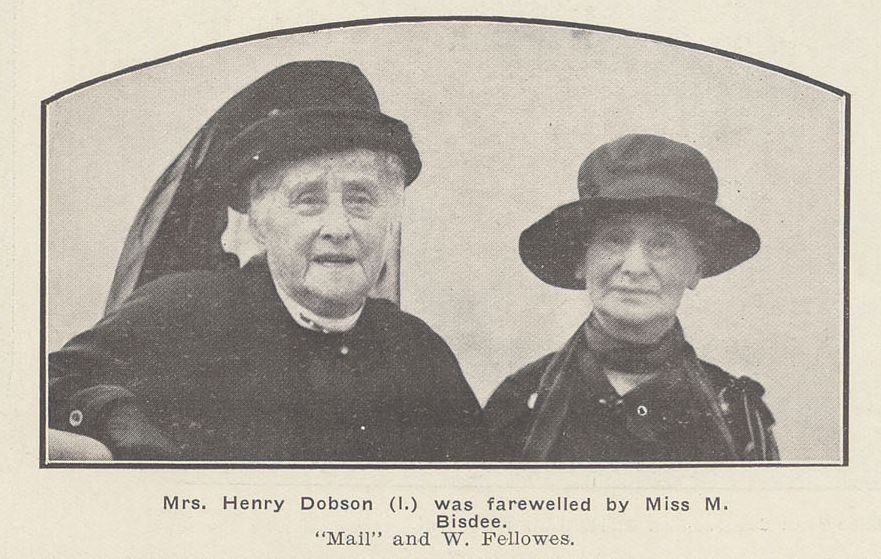

Involvement with the National Council of Women (NCW) and ICW proved to be just the ticket for satisfying Emily Dobson’s energies and ambitions. It gave her the freedom to travel the world, it brought her prestige and desirable social connections, and it gave her a position of power from which she could direct various philanthropic activities. She became the council’s president in 1904, and stayed president until her death in 1934, at age 90! Such was her enthusiasm, Emily also helped set up the Victorian and South Australian branches of the NCW (Jordan, 2004, p. 24). By the time of her death, she had been a president of the Australian National Council of Women and was a vice-president for life of the International Council of Women (The Mercury 7/12/1933).

There was some self-interest in the issues that Mrs Dobson pursued. She was particularly interested in various attempts to provide training for young, working class women in cooking and domestic duties, with the aim to ensure the supply of trained domestic servants. This would clearly benefit her and her friends in society as much as it would the women who received the training. She was prone to be moralistic, with endeavours like the Social Purity Committee (primarily interested in censorship of films), and it is clear that she was interested in helping the ‘deserving poor’ rather than the poor in general. But these tendencies show that Emily Dobson was a woman of her time, culture and class. Renee Jordan, in her Masters thesis, describes Emily as an expediency feminist:

She was not radical and although she worked in the public sphere, travelled widely and was involved with international organisations, it is clear that she believed that women should first be wives and mothers

Jordan, Renee, Emily’s Empire: Emily Dobson and the National Council on Women of Tasmania, 1899-1939, Masters Thesis, University of Tasmania, 2004, p. 36.

It might be considered that Emily Dobson’s domination of so many areas of female public life served to hold women back from more progressive goals, namely suffrage. Unfortunately we don’t have Emily’s personal papers, and the records of the National Council of Women’s from 1899-1906 were not retained, so much of what we know about their stance on issues has to be inferred from what was reported in newspapers. However, one clue that survives that indicates that Emily was not a supporter of universal suffrage. In 1906 she responded to a request for support from a British suffrage organisation, communicating that the National Council of Women believed that some women should have the vote, but that they did not support universal suffrage for men or women (NS325/1/8).

However, Emily was chosen by the Deakin federal government as a delegate to a Women’s Suffrage Congress in Amsterdam in 1908, and her presentation was well received (The Age 26/9/1908). She later stated that she was ‘very proud of’ being entrusted with this role, despite her apparent misgivings about universal suffrage. It may have been because she was not a radical, and committed to not getting involved in politics, that she received support from governments and conservative organisations.

A report of a meeting of Victorian branch of the National Council of Women in 1916 paints an interesting picture of Emily’s influence over the NCW nationally. Correspondence was read from the West Australian and New South Wales branches of the NCW proposing a plan to lobby the Prime Minister’s office for universal female suffrage.

The secretary said the executive was of opinion that the constitution did not admit of their interference in international politics. A cablegram she had just received from the New South Wales secretary on the subject, said they felt in Sydney somewhat the same, and the question was to be referred to Mrs Henry Dobson, president of the Tasmania council, who was also a vice-president of the International Council of Women, and who know how far their rights and privileges extended. Until she had expressed her opinion the question would be held in abeyance.

The Age 29/4/1916

Emily Dobson is usually summed up as the ‘Grand Old Lady of Tasmania’ (The News 16/5/1925). In her time she was well-liked, admired and respected. She also attained enough prominence and power to be considered intimidating, even formidable. It is difficult to separate out the person from the public figure, particularly when so little is known of her private life. In an interview with Renee Jordan for her Masters thesis, Emily Dobson’s granddaughter recalled ‘stark obedience and fear of her grandmother’. She appears to have sustained a strong marriage and a vast social network. It is clear that Emily knew how to hold a room, how to dominate a discussion, how to motivate people and command their loyalty. During one NCW conflict, between the North and South of Tasmania:

Mrs Dobson wished to resign her position as President, but the council in Hobart said if Mrs Dobson resigned, they would all resign. The Northern Branch of the council had passed a vote of confidence in Mrs Dobson at the meeting on January 16th.

Minutes of National Council of Women in Tasmania 3 March 1905, Tasmanian Archives: NS325/1/8

Emily Dobson was a complex and formidable figure. She was a trail blazer for women who wanted to take a more active role in public life. By beginning her work once her children were grown, she was not challenging the role of women in the home, but stretching that role to include a life outside of the home as well. As a member of the high society who enjoyed considerable privileges and resources, her views were often paternalistic and elitist. However, she was also committed and curious. As much as she could be out of touch in some areas, her willingness to learn about and organise for a wide range of causes shows drive, optimism and energy. She seized a great many opportunities. For herself, she found ways to travel the world, to socialise with interesting people and engage in new ideas. For the health and welfare of her community, she contributed to the creation and maintenance of charitable bodies which provided services to the poor, sick, disabled and under-served. For women, she contributed to early feminism by bringing women’s voices and women’s interests into the public sphere. By organising and leading groups of women, she encouraged more women to get involved in causes and learn about the issues affecting them. Her work brought female voices into the public conversation.

Bibliography

Archival sources:

Published sources:

Bolger, P., ‘The Southport Settlement’, Tasmanian Historical Research Association. Papers and Proceedings, Vol. 12, No. 1, (October 1964).

Dollery, E. M., ‘Dobson, Henry (1841–1918)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/dobson-henry-5986/text10217, published first in hardcopy 1981, accessed online 7 March 2022.

Pearce, V., ‘”A Few Viragos on a Stump”: the Womanhood Suffrage Campaign in Tasmania, 1880-1920’, Tasmanian Historical Research Association. Papers and Proceedings, Vol. 32, No. 4 (December 1985).

Reynolds, I. A., ‘Dobson, Emily (1842–1934)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/dobson-emily-5985/text10215, published first in hardcopy 1981, accessed online 7 March 2022.

Taylor, A., ‘Mrs Henry Dobson: Victorian “Do-Gooder” or Sincere Social Reformer, Unpublished BA Hons thesis, University of Tasmania, 1973.

Newspapers:

The Mercury, 28/10/1893, 10/10/1932, 7/12/1933, 6/6/1934,

Fascinating story. In regards to the Clipper articles, the more things change – the more they stay the same. I too am descended from the same Smith Family. The early Smith family history is equally as fascinating. What an amazing lady. A truly inspirational life. Thank you for sharing.

What an inspiration is Emily Dobson / Lempriere!

Although Emily’s birth is registered in the Hobart District, rather than Tasman, it is registered some time later by her mother C[harlotte] Lempriere, whose address is given as Port Arthur, and Emily’s father is noted as the Dpty Asst. Com. Genl.

Thank you for sharing her story for International Women’s Day. I’ll be sharing this with a good friend who is a descendant of Thomas and Charlotte Lempriere.

This is wonderful. Thank you for publishing this on international women’s day.

Not wishing to blow my own trumpet but I have just published Leading Amateurs about the career of her niece. Lucy Benson (1860-1943) was Australia’s first female conductor. NB Lucy lived with Emily’s mother in Bellerive at her home called Rozel. Emily and Lucy did theatricals together.

Thank you Anne, so nice to know about that connection.