Adventurous Beginnings – Te Bibilia Tapu Ra

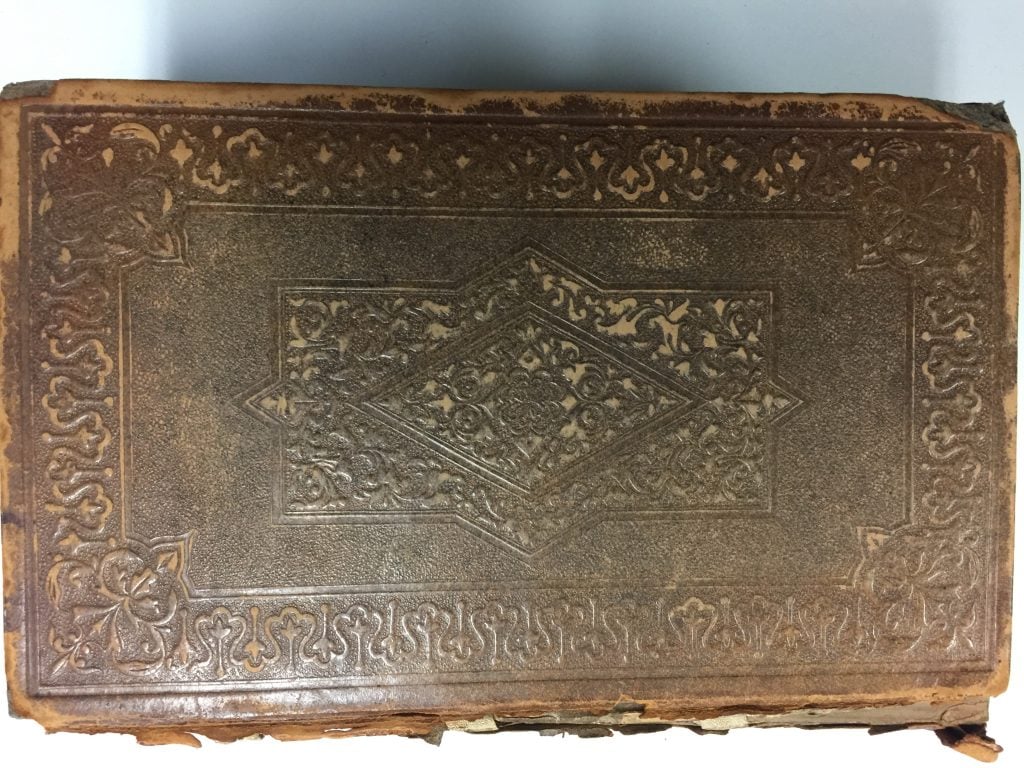

Books travel. Throughout their lives, they are passed from hand to hand: given, borrowed, stolen, buried, discovered. Like all travellers, they also gather stories. This is the story of the Raratongan Bible, Te Bibilia Tapu Ra, in the Australian Collection of the Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office. It begins on a Pacific island and ends in Tasmania, and its story is fascinating. Interested? Read on!

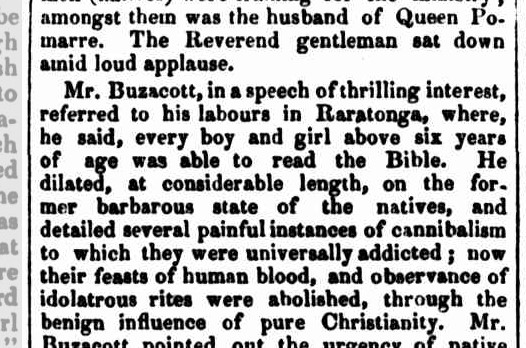

All around the world in the early nineteenth century, missionaries were translating the Bible into indigenous languages. This was supposed be the first step in transforming colonized peoples, spreading literacy and notions of ‘respectability’ while erasing traditional power structures, customs, and beliefs. Of course, it didn’t always work that way. Missionaries seldom spoke local languages as well as they thought they did, and usually relied on local people to help them. As a result, these texts often fused old and new beliefs together, and the children taught in mission schools often became vocal and eloquent leaders in their communities – as Walter George Arthur and others did in Tasmania.

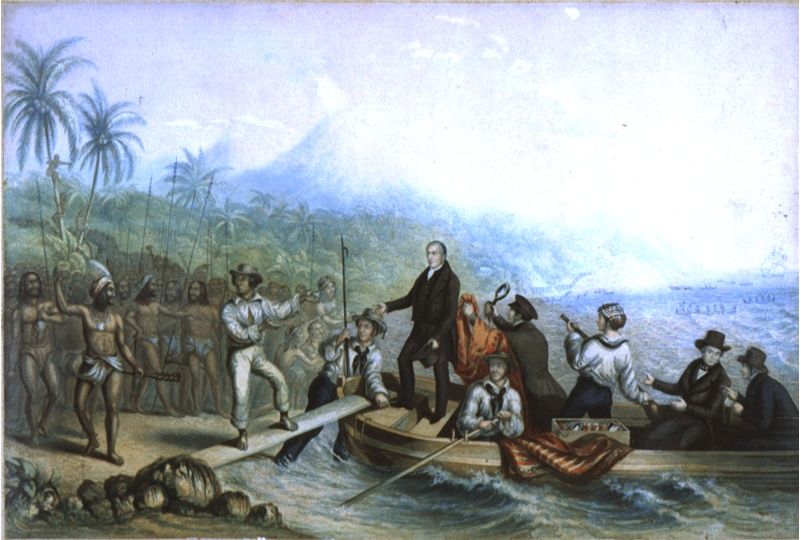

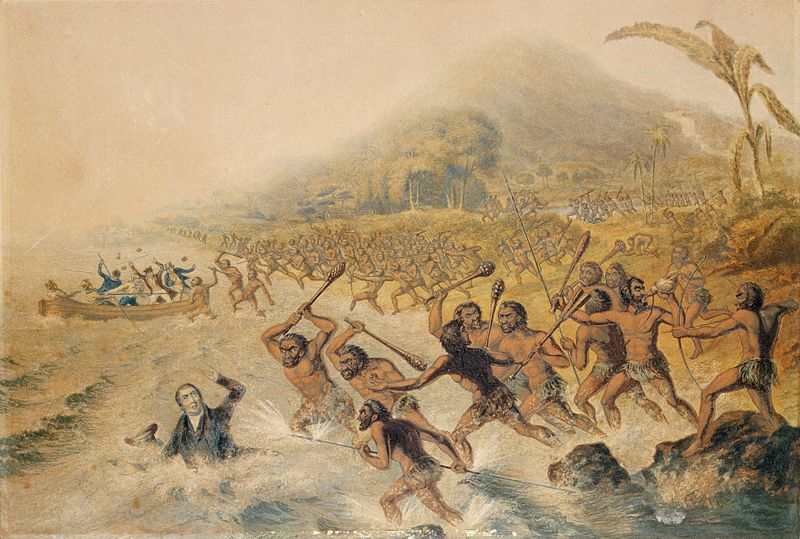

The initial translation work for Te Bibilia Tapu Ra was started at the island of Rarotonga in the Cook Islands in 1828 by members of the London Missionary Society; John Williams, Charles Pitman, and Aaron Buzacott. After many years of work, Williams took the first part of the Bible back to London, had it partially printed, and then returned to the South Pacific to continue his preaching and translating. In 1837 he traveled to Erromango in the New Hebrides (Vanuatu) to meet with, he hoped, some potential new converts. It was a fatal decision.

Williams was unaware that the young sons of a local chief had just been murdered by a sandalwood trader, and tensions were running high. When he left the beach and wandered inland in search of converts, he crossed a ritual border meant to keep outsiders away. He and his companions were immediately chased back to the beach, killed and eaten. When the news reached Britain, Williams was hailed as a martyr. His death was compared to that of Captain James Cook in Hawai’i fifty years earlier, and was used to drum up support for missionary initiatives around the world.

Williams’s colleagues Charles Pitman and Aaron Buzacott continued the translating on Rarotonga and had parts of Te Bibilia Tapu Ra printed locally. But in 1846 a cyclone destroyed most of the manuscript and they had to start again.

In 1847 Buzacott returned to London with Leota, a Samoan, and they worked together to continue the translation. Finally, in 1851, the manuscript was finished and 5000 copies were printed. After some promotional visits they arrived back to Rarotonga where the Bible was a huge success with the local Christian population.

But how did the copy of Te Bibilia Tapu Ra end up in Tasmania? The Reverend Buzacott, Mrs and Miss Buzacott arrived in the colony on the John Williams, or ‘the Missionary Ship,’ on the 1st of November, 1851 along with their colleague the Reverend William Gill. They had with them the 5000 copies of the translation of the Holy Scriptures (listed on the cargo as ‘Missionary’s Supplies’).

The volumes were to be sold for 8 shillings each, with the proceeds returning to the London Missionary Society. While in Tasmania, the missionaries conducted services to large and rapturous audiences including ‘the schools of various denominations assembled with their teachers, parents and friends.’

The Reverend Buzacott’s speech to one of these ‘rapturous audiences’ was reported in the Colonial Times:

When the Buzacotts left Hobart, the copy of Te Bibilia Tapu Ra stayed behind, having been presented to the Governor as one of the first books of the new Tasmanian Public Library. It bears this inscription, ‘Presented by the Revd. A Buzacott to his Excellency W. Dennison and by him deposited in the Tasmanian Public Library, he had established in June 1849. The inscription is signed W.D. 6 Nov [18]’51.’

In December 2009, descendants of the Williams family travelled to Erromango to mark the 170th anniversary of his death, where they accepted the apology of the President of Vanuatu, Iolu Johnson Abil in an act of reconciliation.

Many thanks to Amanda Double, Librarian in Collections Development, for all of her research that contributed to this blog.

Further reading:

Online Sources:

For more about the language of the Cook Islands (as well as some neat photographs), have a look at this blog from the Alexander Turnbull Library in New Zealand.

Primary Sources:

Secondary Sources:

Edited by Annaliese Claydon, archivist, TAHO