The Lanney Pillar – Installation at the Allport Gallery

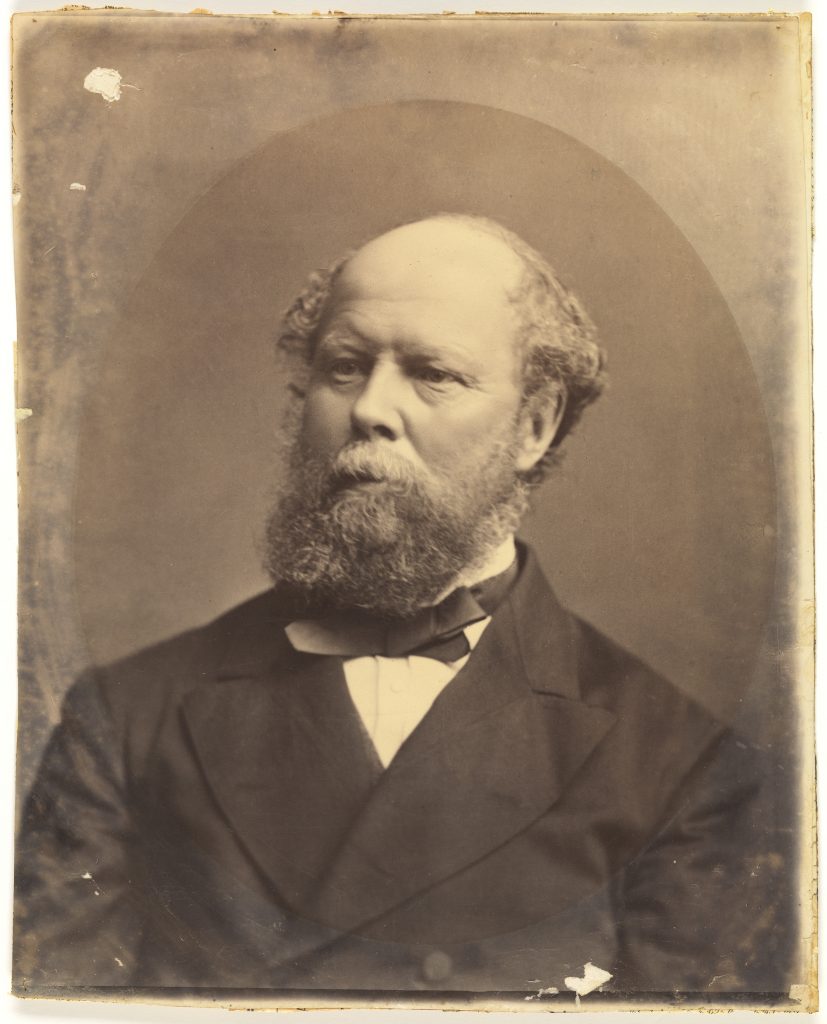

In January 1889 a bronze statue of William Lodewyk Crowther (1817-1885) was erected in Franklin Square where it stands today. Made in England by the sculptor Signor Racci and shipped to Hobart, it was placed on a locally designed plinth in the same civic square as the Franklin statue which commemorates the Governorship of Tasmania by the Arctic navigator Sir John Franklin.

The Hobart Mercury, Thursday morning, January 10, 1889 reported on the ceremony to unveil the Crowther statue. The Chairman of the committee said:

This memorial may remind future generations, that even monuments may perish, but deeds, good or bad, never die.

The Mercury 10/1/1889 p. 3

As it turns out – prescient words.

WL Crowther’s Obituary in the Tasmanian News (13/4/1885) highlights his medical accomplishments and noted his professional self-sacrifice and philanthropy when it came to the medical treatment of the poor. It also spoke of his enterprising and speculative nature and his involvement in many commercial enterprises seen as a benefit to the colony. It states that he:

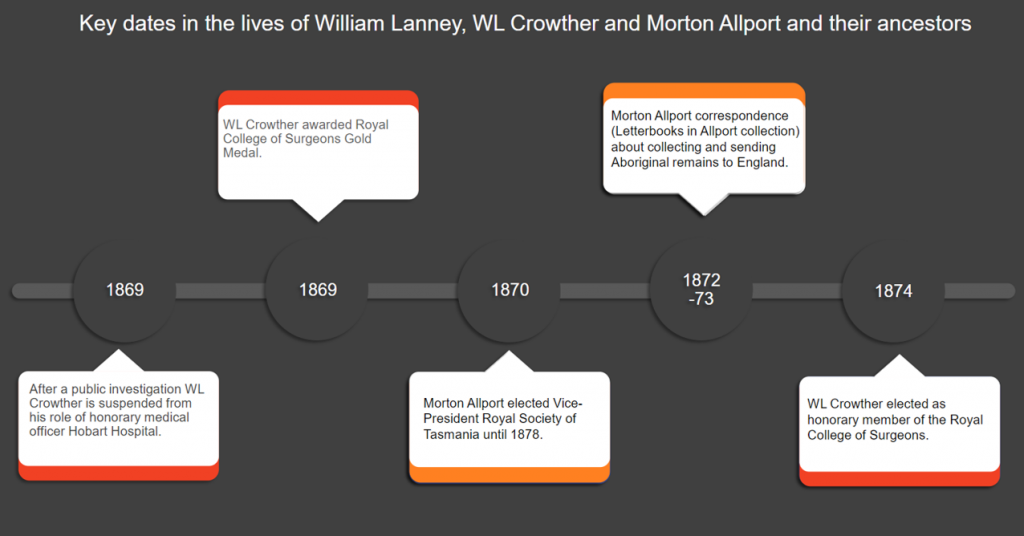

had the honour of receiving a gold medal from the Royal College of Surgeons, England, for donations in the shape of natural curiosities (the head of the last male aboriginal of Tasmania being one), and was created a Fellow also by the same College in 1874.

Tasmanian (Launceston, Tas. : 1881 – 1895), Saturday 18 April 1885, page 10

In 2021 as part of the Hobart City’s Aboriginal Commitment and Action Plan and in response to members of the Aboriginal Community expressing their objections about the Crowther statue, the Council commissioned four temporary public art pieces, by local artists, to offer a response to the presence of the Crowther statue in Franklin Square.

In all cases the artists felt compelled to draw attention to the fact that WL Crowther was involved in the ghoulish deed of obtaining William Lanney’s skull.

Roger Scholes and Greg Lehman, The Lanney Pillar, 2021. Mixed media was the second of the four artworks and was displayed in Franklin Square next to the WL Crowther statue from June – August 2021.

Today we have a slightly adapted version of The Lanney Pillar in the Allport Library and Museum of Fine Arts.

About the work

The Lanney Pillar is an installation designed to encourage conversation. It was commissioned in 2021 as part of the City of Hobart’s Crowther Reinterpretation project in response to the statue of WL Crowther in Franklin Square. By exhibiting The Lanney Pillar at the library we aim to honour and celebrate the life and history of William Lanney. A series of talks will be held during the exhibition which will delve further into the interweaving themes of history, identity, repatriation, science, law and collecting.

The Lanney Pillar is a collaboration between Tasmanian Aboriginal writer and curator Professor Greg Lehman and internationally recognised Tasmanian filmmaker Roger Scholes. Through images and film Scholes and Lehman provide audiences with a retelling of William Lanney’s life.

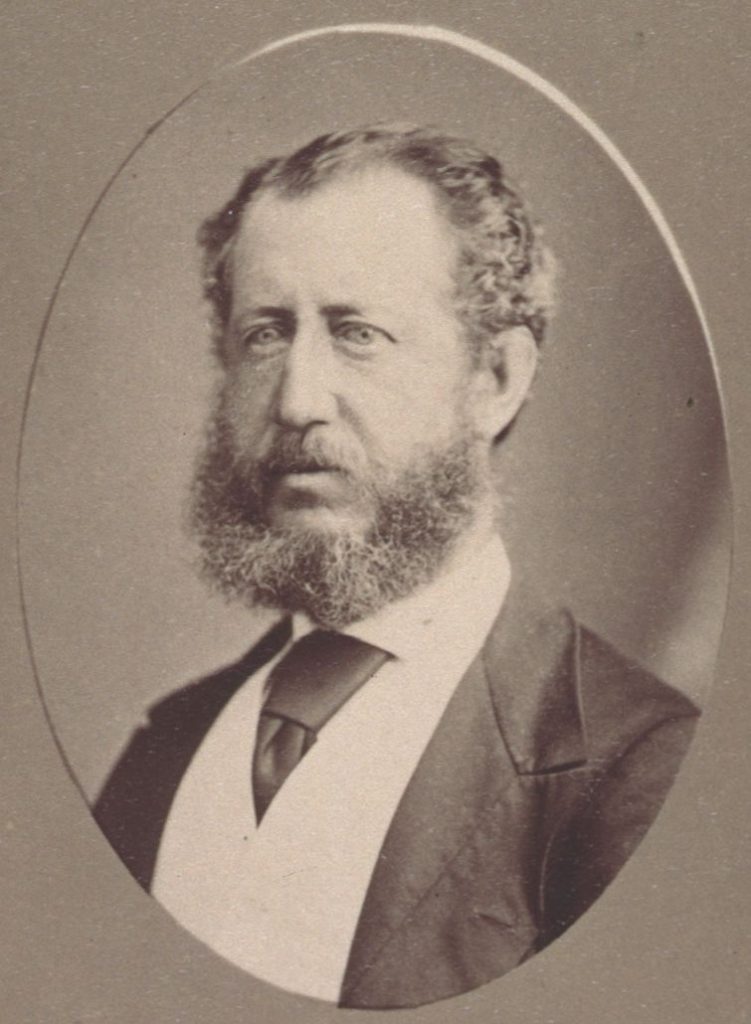

Lanney’s story has often been told through his connection to William Lodewyk Crowther and Crowther’s involvement in the desecration of Lanney’s body. What is lesser known, is that Morton Allport was also a key figure in the scientific community and the mid-nineteenth century trade of human remains.

The State Library of Tasmania is the beneficiary of the Allport and Crowther collections through the donation of the WL Crowther Library and bequest of the Allport Library and Museum of Fine Arts in the 1960s. As a cultural institution, we also respectfully acknowledge the lasting trauma experienced by palawa / Tasmanian Aboriginal people that has resulted from the actions of Morton Allport, WL Crowther, and other individuals in the name of scientific research.

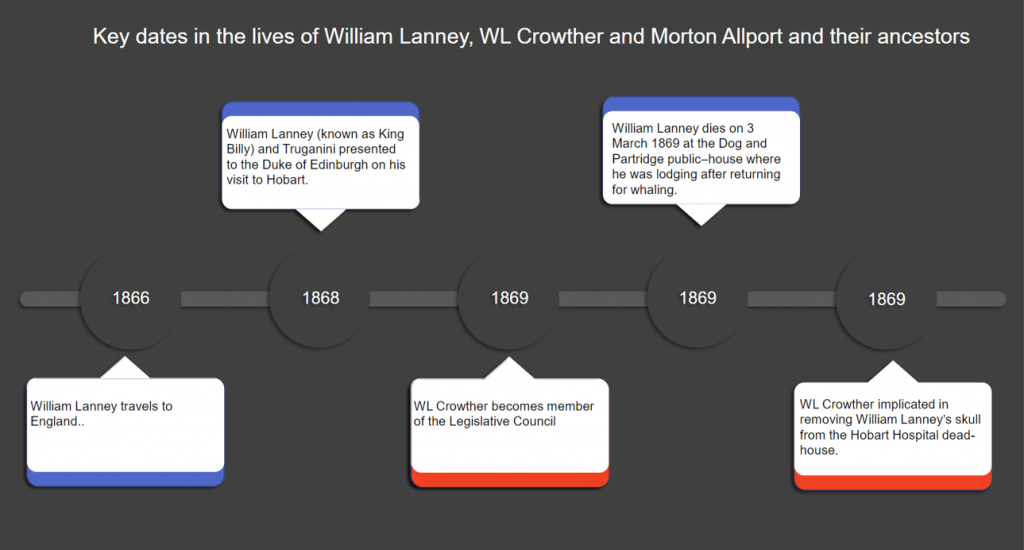

The life of Tasmanian Aboriginal man William Lanney (1835-1869) has been overshadowed by what happened to him after his death. Few of us know anything about his extraordinary life. The Lanney Pillar seeks to reclaim the story of William Lanney’s life from the historical actions of WL Crowther. William Lanney was one of the last palawa / Tasmanian Aboriginal people born on the traditional Country of his ancestors. In 1842 Lanney and his family were exiled by the Governor to Wybalenna on Flinders Island. As a young man, Lanney joined the crews of the whaling ships sailing the Southern Ocean to Chile and beyond. Lanney’s shipmates called him ‘King Billy’. In 1867 he sailed to England to meet Queen Victoria and later in nipaluna / Hobart he met with the Duke of Edinburgh, advocating for his people.

Lanney was an independent man, respected by the people of Hobart Town who lined the streets for his funeral. When WL Crowther took his body from the morgue, Lanney’s dignity was also stolen.

Artist statement for The Lanney Pillar from Greg Lehman and Roger Scholes

The Allport connection

Libraries Tasmania houses two large collections of books, manuscripts, objects and art, donated to the Library in the 1960s. The first collection is named the WL Crowther Collection and was donated by his grandson WELH Crowther. The second is the Allport Library and Museum of Fine Arts Collection which was donated by Henry Allport. Both these collections contain items collected by the Crowther and Allport families over four generations living in Tasmania from 1825.

Both families had members who were intricately involved in the collecting of Aboriginal remains, including the skull of William Lanney.

This exhibition presents some of the material from the collections which helps to explain and reveal more about this trading in human remains which reached its height in the 1870s but unfortunately continued into the twentieth century.

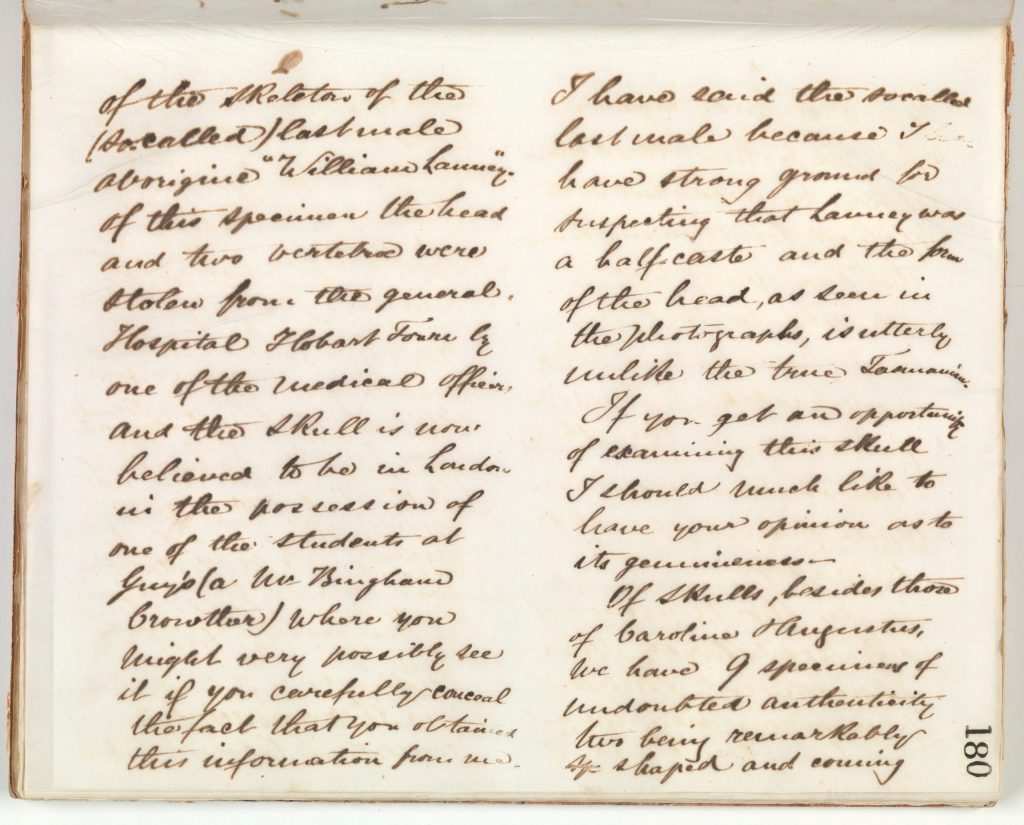

Morton Allport’s letters tell of his connection to men in England eagerly requesting remains and rewarding him with scientific membership and books and articles. In the letter pictured above Morton Allport mentions that Lanney’s skull might be with WL Crowther’s son Bingham Crowther at Guy’s hospital in England.

Morton Allport, Allport Library and Museum of Fine Arts, State Library of Tasmania

WL Crowther (1817-1885) and Morton Allport (1830-1878) both actively acquired Aboriginal remains. For a full account see Helen MacDonald’s book Human Remains : episodes in human dissection

Dr Julie Gough, a trawlwoolway artist from northern lutruwita/Tasmania was one of the four artists commissioned in the Hobart City Crowther Reinterpretation project. She has been quoted in the 2021 Pathway to Truth-telling and Treaty report, making the comment that:

The analysis of contested histories and abandoned places is most akin to detective work and forensic analysis.

Julie Gough in Pathway to Truth-telling and Treaty, Report to Premier Peter Gutwein, Prepared by Professor Kate Warner, Professor Tim McCormack and Ms Fauve Kurnadi (2021).

This is certainly true when we delve into the archives donated by the Crowther and Allport families, and it highlights the importance of all archival collections which, when searched and analysed, can reveal hidden truths and different perspectives.

Statues are not so much a record of history but rather of historical memory. They reflect what somebody at some point thought we should think. Putting a statue up has always been a powerful symbol and over the course of history we have also seen that pulling them down is another. They have become part of the story of how historical memory is constructed and challenged (see Interview with Alex von Tunzelmann). You can borrow Alex’s book here: https://libraries.tas.gov.au/Record/Library/SD_ILS-1371283.

Portrait statuary like most of the statues that are now in our cities was a 19th century revival of the Renaissance revival of the classical style. Individual heroism of ‘the great man’ was in fashion.

When reading the newspaper report of the unveiling of the Crowther statue we get a sense of it being a spectacular event at the time. It attracted a crowd, providing those in power with a novel opportunity to honour their ‘old friend’, and to be pleased with themselves for being able to organise such a high quality statue by Signor Racci of London. The Committee had debated other forms of memorial, such as an oil painting or having a Museum of Arts established to honour WL Crowther (The Mercury 10/1/1889, p.3).

Morton Allport clipped out the newspaper report about the statue and stuck it in his collection of press clippings, which is on display in this exhibition.

In 1865, 24 years earlier, a bronze statue to commemorate the Governorship of Tasmania by Sir John Franklin had been erected in the same civic square and a third would be added in 1922 – a bronze statue of King Edward VII.

There is an increasing critical awareness around continued structural racial inequalities in contemporary society, heritage interpretation and historical representation. This awareness is not to be seen as something inhibiting our use of historical archives – instead, it can energise studies and suggest different ways of reading the record that challenge, inspire and help us uncover the complexity and nuance of historical records.

As the custodians of significant documentary evidence relating to the Crowther and Allport families, and as part of the Culturally Safe Libraries Project, Libraries Tasmania has the opportunity to present key letters, documents and photographs held in our collections that relate to these issues.

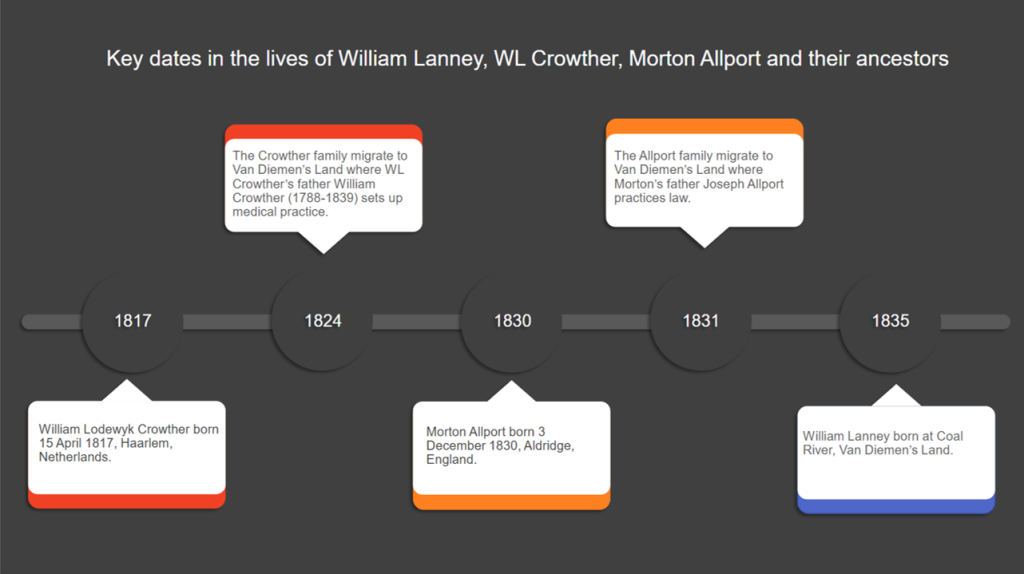

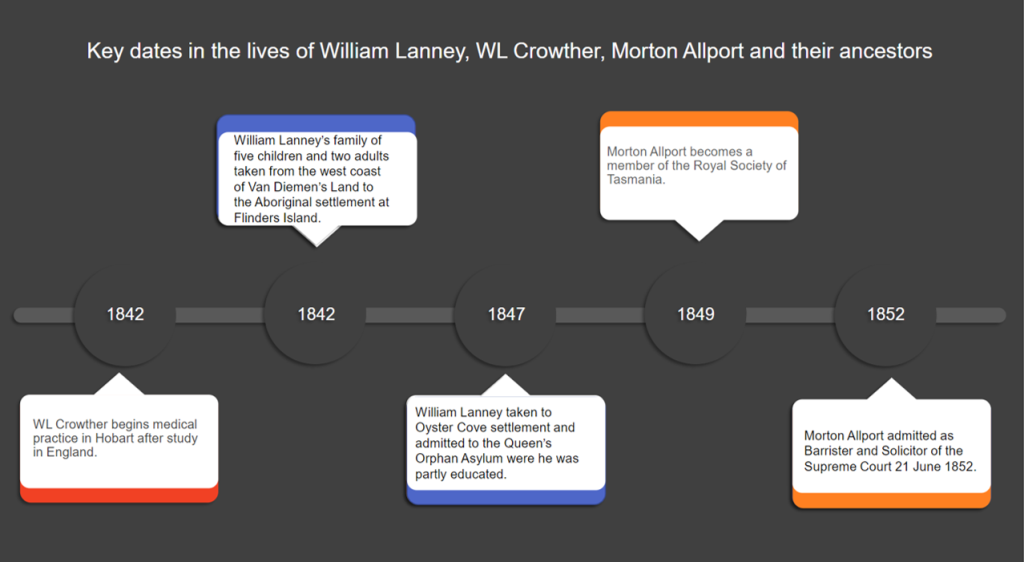

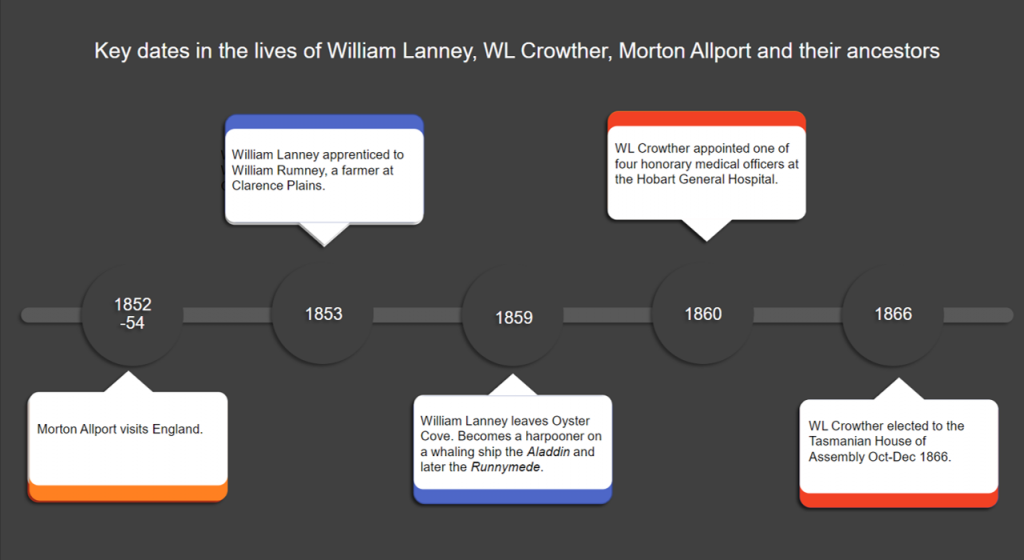

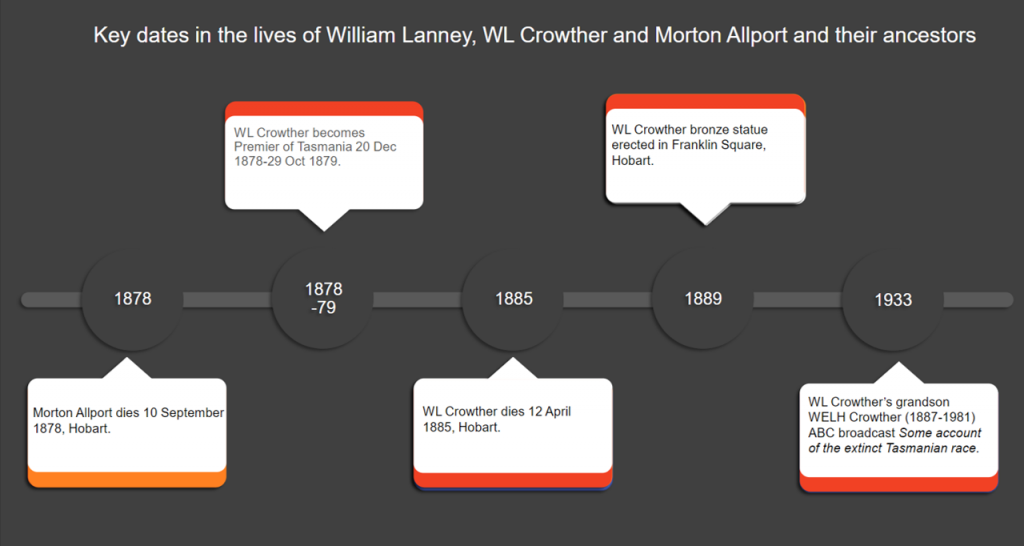

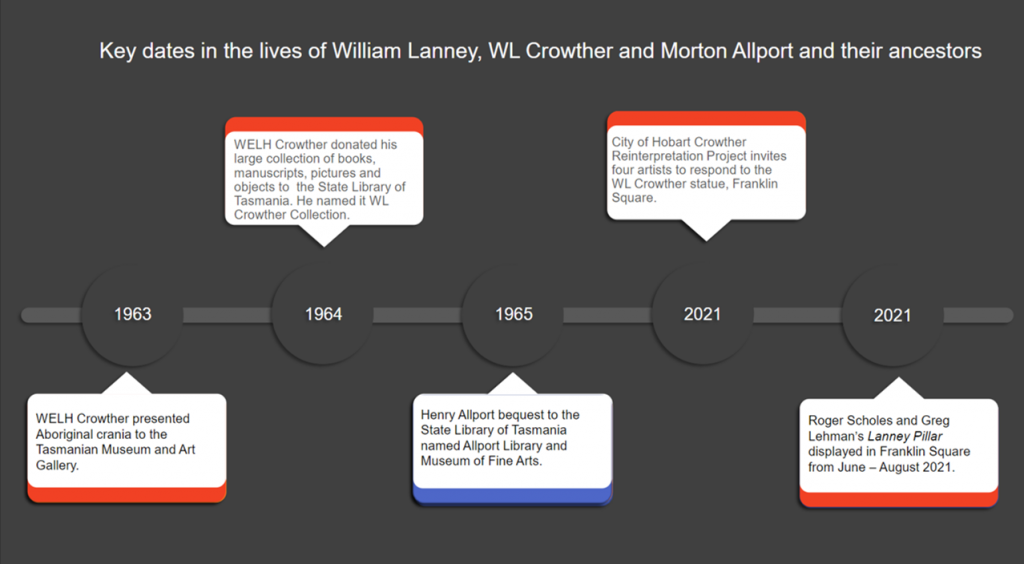

This timeline shows the overlapping of the lives of William Lanney, WL Crowther and Morton Allport:

The Lanney Pillar in the Allport will be on show until Saturday 25 June 2022 and is accompanied by a lecture series which will be made available on the Libraries Tasmania SoundCloud and YouTube channels.

I visited Tasmania for 5 weeks earlier this year and was horrified to observe how little attention was paid to aboriginal history. The best curated information was at the visitors centre at Cape Portland wind farm and I don’t think many people go there! Great to see this online. Keep up the good work.

Thank you for this in-depth interpretation.The timeline was particularly potent in providing an equal comparison of the lives of the three protagonists, two of which have a written legacy of letters etc to fill out their personas, while the third we have to fill the gaps. Its interesting that William Lanney was born in the Coal River Valley, but his family were removed from the West Coast, so presumably they migrated there in an attempt to avoid persecution.

Thank you for your response Ruth – you are so right about filling the gaps – we have a lot of work to do! We need to keep looking, thinking, exposing and providing easy access at every opportunity.

Please come and visit us when next you are in at 91 Murray Street.

Thank you! I don’t get to Tassie from the mainland very often, so it’s great to find this exhibition curated online. As a descendant of British conquerors and Irish convicts to Tasmania, I abhor their role as cogs in the invasion machine that almost destroyed the First Nations people and culture. I find the lack of human dignity imposed on Aboriginal people distressing and shameful, and wish that the Australian War Memorial would recognise the ‘Black Wars’ as part of Australia’s war history. This chapter is undeniably part of our dark history as a nation, and needs to be widely known and acknowledged.

Hello Karen – thank you for your heartfelt interest and thoughts. Next time you are in Tassie I hope you can come and visit us at the Allport Library and Museum of Fine Arts.

Thank you. This was most informative, though I am not resident in Tasmania. I spent some time working there in 1950 and became interested in the indigenous people of the past.

Thank you Gwen it’s good to know you are interested in these issues and can keep in contact – much appreciated.